A few migrant workers — their clothes smudged from a long day of construction — stand in the aisle, hesitant to sit down. They shift their weight, glance around, but stay on their feet. This isn’t a rare scene. In fact, it’s what inspired a recent wave of reflection across Chinese social media and news outlets about hygiene, dignity, and the invisible burdens carried by those who built the very cities we live in.

As of the end of 2024, 67 percent of China’s population — that’s 940 million people — lived in urban areas. Behind this sweeping statistic lies nearly five decades of relentless urbanization. And at the heart of it all: the country’s vast migrant worker population. Every gleaming skyscraper and freshly renovated apartment owes something to their sweat, their labor under the sun.

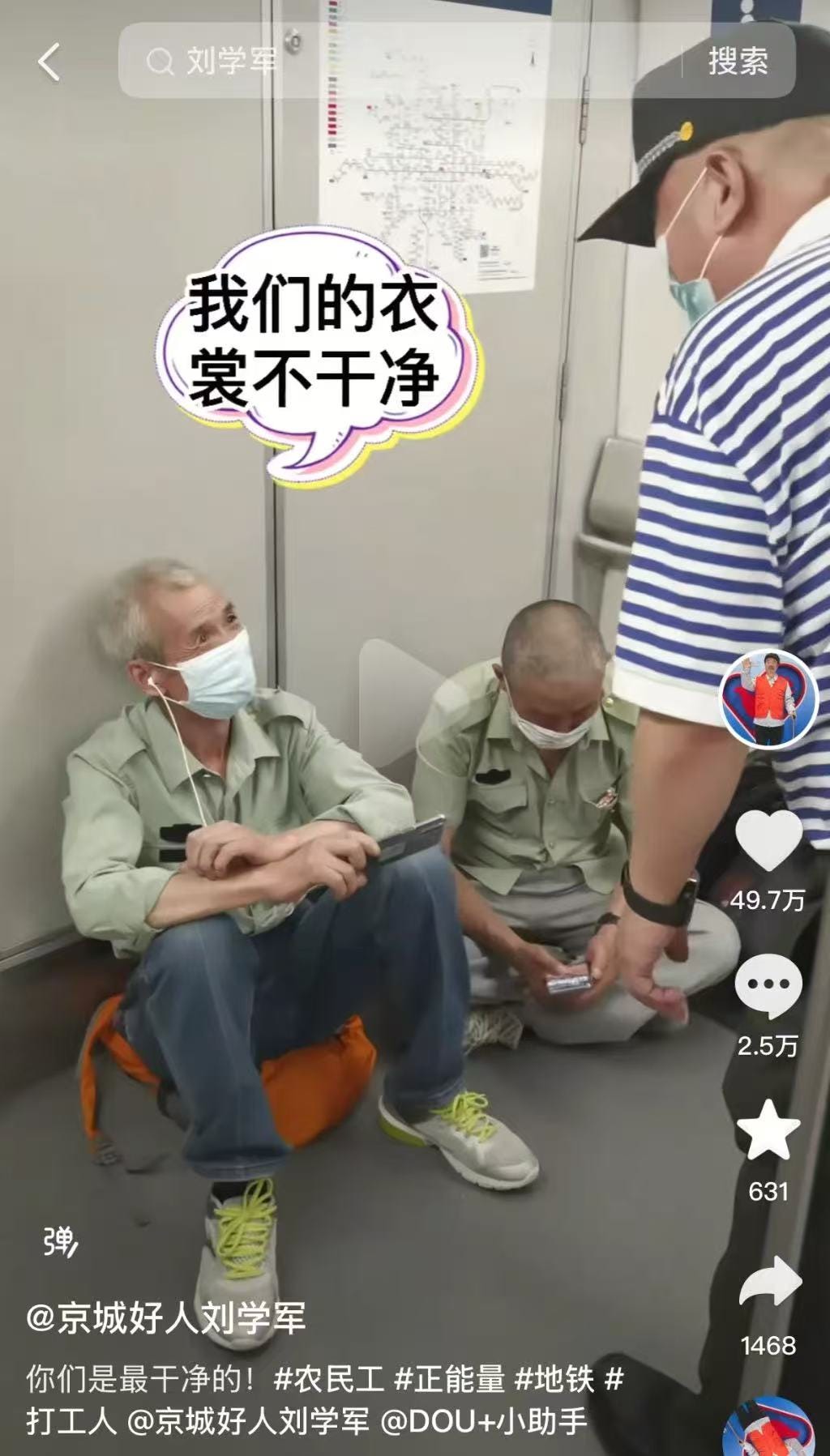

But once the workday ends, many face everyday hurdles that go unseen — including something as basic as getting home, or finding a place to wash up. A Douyin creator who goes by the name “Good Samaritan Liu Xuejun in Beijing” (京城好人刘学军)has been documenting such encounters, offering migrant workers directions, a word of kindness, and above all, understanding. In one video, Liu empathizes with a worker who hesitates to sit because he worries about staining the subway seat — not out of fear, but out of courtesy.

A recent feature by The Paper (澎湃新闻) took a deeper dive into these lives — not just the hardships, but the voices and quiet dignity behind them. It’s a powerful piece of human-centered reporting that deserves more attention.

One final thought: it’s natural to feel uncomfortable when we see someone whose clothes are visibly dirty. That instinct isn’t inherently wrong — it’s human. The more important question is what we choose to do next. Stories like Liu Xuejun’s and reporting like The Paper’s offer us a path forward — not by denying discomfort, but by meeting it with empathy, solutions, and care.

“I’m Covered in Dust. How Can I Sit?” | A Construction Worker Rides the Subway

Qi Jianjun had just finished a long day leveling floors with cement and sand. Exhausted and coated in dust, he stepped onto the subway. But before he could rest, a familiar question surfaced: Should I sit like this?

This quiet dilemma is one that many workers in the city know all too well.

On April 17, a confrontation on Beijing Subway Line 5 brought this tension into public view. A passenger grew angry at the sight of the man next to him, criticizing his appearance. “You look like a beggar, covered in dust, squeezing in here,” he said. His insults escalated quickly, even calling the man a “bastard.” The man he targeted was wearing a gray jacket, with visible traces of white and gray dust on his pants and shoes. He sat upright, hands folded over his chest, back straight, and positioned at the edge of the seat. Between his feet were two full plastic bags, and in order to keep them steady, he had spread his legs slightly, which brought them closer to the angry passenger.

He tried to explain that he had not leaned back or tried to take up extra space. But the insults did not stop. It was only when another commuter stepped in that the scene changed. “I’m happy to sit next to him,” the person said, taking the middle seat between the two men. The moment was caught on video. It spread rapidly online and sparked widespread discussion. Follow-up reports identified the man who had been insulted as a renovation worker employed at a curtain mall in Beijing.

In cities, reflective vests, hard hats, safety boots, and paint buckets silently identify workers long before they speak. But when labor leaves its mark in the form of dust, sweat, or cement stains, how do these workers navigate shared public spaces while preserving their dignity? The answer may lie in the very dust on their clothes.

“I’m Covered in Dust. How Can I Sit?”

Piles of yellow sand and gray cement formed small mounds in the center of a room. After a full day’s work, these would be spread evenly by Qi Jianjun as the base layer for new tile flooring.

Qi is 53 years old and comes from Zhoukou, Henan Province. This is his seventh year working away from home. Last February, through his wife’s introduction, he took a foreman job on a highway overpass project subcontracted by her younger brother. They agreed on a monthly wage of 9,000 yuan. But as payments were delayed again and again, that monthly salary effectively turned into a lump sum at the end of the year. The stress left him pulling at his hair in frustration. After the Lunar New Year, unable to recover his wages, he cut ties. He blocked both his wife and brother-in-law, shaved his head, and went back on the road. Once again, he took whatever day labor he could find to get by.

Now, he crouches beside freshly poured cement, one hand resting on his knee, toes gripping the floor, his upper body leaning forward. He stretches his other hand out with a trowel, smoothing the cement from far to near. Then he twists his torso, shifts his weight back, and moves forward by a step. He repeats this process hundreds of times every day.

Qi Jianjun leveling a cement floor

Cement and sand are fine-grained and mix into a wet, heavy paste that is difficult to control. Splashes are common during the mixing and pouring process. When he squats down to spread the mix, his knees sometimes touch the ground. Once dried, the cement leaves behind white, yellow, or gray stains. Often by midday, the sleeves, pant legs, knees, and collar of his clothing are already visibly marked.

After lunch, Qi usually gets a 30-minute or one-hour break. The site is full of sand and cement, and there are no chairs. He often looks for a cleaner corner to lean against. Sometimes, if there is an empty room nearby, he lies on the cement floor for a nap. To keep his head off the ground, he props it up with his elbows or leans against the wall. Each break leaves his clothes a little more soiled.

A worker napping on the ground, photographed by Qi Jianjun

It is not just his clothes. Qi Jianjun’s hair often ends up covered in dust too. Over the past six months, as his hair grew out, he gave himself a trendy look, a small patch left on top, dyed bright red. From a distance, it resembled a tiny volcano. He is particular about keeping it tidy. But when his fingers, stained with cement, run across his scalp, the bright red quickly becomes dulled by a layer of white dust. White streaks remain where his fingers passed.

At four in the afternoon, after smoothing out the final patch near the doorway, he stepped outside. Once the foreman checked the work, he would receive his pay for the day. That day, however, the foreman was too busy to drive him home. Qi had to take the subway in his cement-splattered clothes.

At around four thirty, the train was not too crowded. As he stepped inside, he spotted an empty seat and walked toward it. Just as he was about to sit, a voice stopped him. “You are so dirty. How can you sit here?” He looked up. A middle-aged woman sitting next to the seat was staring at him. A wave of frustration rose in him. He had been up since four in the morning, working all day leveling floors. His legs and back were aching, and he still had an hour and a half before he could get home. He wanted to sit. But the look in the woman’s eyes made it clear that there would be a confrontation. So he said, “Sorry. If you think I am dirty, I will sit on the floor.”

He leaned against the railing and sat down. Other passengers quickly spoke up for him. One turned to the woman and said, “Do you own this place? This is a public train.” An older commuter waved to Qi and said, “Don’t listen to her, sir. Sit down. Let’s see if she tries to stop you.” But Qi just replied, “Forget it,” and stayed on the floor.

With dust on his face and clothes, he said he felt he had no grounds to insist on sitting. “Other people are clean. What if I brush against them?” he explained. He also pointed out that the woman had not used any abusive language. “She only said I was dirty. If she had insulted me, I would not have stayed silent.”

This was the only time someone had directly told him not to sit. Most of the time, people who minded would simply move away.

Liu Xuejun sees workers sitting on the subway floor almost every day. After retiring due to illness, he became a volunteer at Beijing subway stations, offering directions and handing out candy to passengers with low blood sugar. He has noticed that many workers choose to stand or sit on the floor even when there are empty seats, simply to avoid making the seats dirty. Once, he saw an older worker with a large bag, gripping the handrail and swaying as he stood, eyes closed. Liu quickly helped him into a seat and asked, “You paid just like everyone else. Why not sit down?” The man pointed at his jacket and said, “People do not like it when you are dirty.” Liu hears that kind of response all the time. He always tries to reassure them. “You are not dirty. Not at all. You are the ones building this city.” When someone is especially hesitant, he hands over a tissue and suggests, “It is fine. Sit down. You can wipe it clean when you leave.”

Liu Xuejun encouraging a worker to take a seat on the Beijing subway

Wanting to sit but choosing not to—for many workers, it is a quiet standard they set for themselves.

A Shanghai Metro employee told reporters that, according to Article 10 of the Shanghai Rail Transit Passenger Code, passengers who are barefoot, shirtless, wearing visibly dirty or greasy clothing, intoxicated and causing disturbances, suffering from serious infectious diseases, or unaccompanied with mental health issues that may pose a safety risk, are not allowed to enter stations or ride trains. Beyond these specific cases, the Metro doesn’t have any formal dress code. If a seat gets dirty, it’s usually cleaned by a sanitation worker who boards at the next station.

That said, the employee also pointed out that sitting on the floor, something some workers resort to, is a safety concern. “If the train brakes suddenly and there are people standing nearby, sitting on the floor can be dangerous,” they explained. Station attendants typically ask passengers sitting on the floor to stand up and hold onto the handrails.

For many workers, it’s a no-win situation: sit on a seat and risk being judged, sit on the floor and be told it’s unsafe, or stand up despite being bone-tired after a long day. Some workers told reporters they’ve thought about changing clothes before getting on the train, but the reality is, most construction sites don’t have anywhere to shower or change.

No Place to Clean Up or Change at Construction Sites

After a full day of dusty, sweaty work, Qi Jianjun still can’t take a shower before heading home. The kind of work he does, leveling floors, usually comes after plumbing and wiring, meaning the building is still in its bare-bones phase. There’s no hot water, no bathroom doors, no tile floors, no showers. The site might have a temporary water supply, but it’s only cold water, and it’s meant for construction use.

It’s not just residential renovations. Factory sites, schools, restaurants, office buildings—most of them don’t have showers either. Several seasoned workers told reporters they’ve never had a place to shower on site. “Even if there was a shower,” one said, “the client wouldn’t let you use it.” A staffer at a renovation company added that many homeowners don’t even allow workers to use their toilets, let alone take a shower. So most workers have no choice but to wait until they get home to wash up and change.

Qi said that most days, the foreman gives him a ride. But when that’s not possible, he’s left to make his own way home. If the site is far, he often ends up riding the subway or bus covered in dust, simply because there’s no other option.

Qi works freelance, so his hours aren’t set. Some days he’s paid by the hour, but on days when he’s paid by the job, he might work up to 12 hours to finish everything. Even when paid hourly, he often chooses to work over 9 hours a day to earn overtime—30 yuan an hour.

And these days, with work being uncertain, he sometimes has to get up at 4 a.m. to wait at a day labor market, hoping to get picked up for a job. By the time he finishes work and boards the subway home, it’s already evening. He’s dead tired and just wants to sit. His clothes are already filthy, so why not just sit on the floor?

Because renovation jobs are short-term and scattered across different sites, and because workers don’t have a place to clean up, they’re especially noticeable when taking public transit.

And it’s not just decorators. Workers who handle piling, bricklaying, concrete pouring, or steel welding often end up covered in cement, mortar, dust, and debris from materials and welding.

Bricklayer Cao Daoyin said none of the sites he’s worked on had shower facilities. If he wants to wash up, he has to return to the dormitory or his rented place. Dorms are usually located a good distance away from the worksite, not right next door. That’s partly for safety, with each area requiring face scan access, and partly to ensure a quieter rest environment. “If everyone stayed right next to the site, there would be overnight shifts and constant noise. No one could sleep.”

Cao just wrapped up a job at a factory construction site that employed over 2,000 workers. It takes more than 20 minutes to walk from the gate to the dorm entrance. Most people use shared bikes, but Cao doesn’t know how. No matter how big the site, he walks, sometimes over 30 minutes one way.

When deadlines are tight, some workers are brought in for short-term help, for just 10 or 20 days. They don’t live near the site, and after work, they have to take the cheapest and fastest option to get home: public transit, still in their dusty gear.

To shower in the dorm area, workers have to go through facial recognition. Even when they get in, evenings are peak time for showers. “When it’s crowded,” Cao Daoyin said, “the line can be over an hour long.” On top of that, the water sometimes gets cut off. Since they often work late to meet deadlines, if they finish at 10 p.m. and then try to shower, they might miss the last subway. So most just tough it out and wait to wash up at home.

It’s not just temporary workers, construction crews at downtown sites rely on public transit too. Because space in city centers is tight, most sites don’t have dorms. And if they do, beds are limited. Some sites in busy areas even strictly forbid overnight stays. “It gets messy, looks bad, and people complain,” explained Cao’s coworker Wang Hui.

So companies usually rent apartments farther out. But rent in the city center is expensive, especially in places like Beijing or Shanghai. A place for five or six workers can easily run over 4,000 yuan (about 560 U.S. dollars) a month. To save costs, companies rent even farther away, meaning workers have to commute by subway or bus.

Chen Jiang is one of those workers. That evening, wearing a bright yellow hard hat and orange reflective vest, he boarded Shanghai’s Metro Line 12 at West Nanjing Road Station. He stood near the car connection, the spot with the least people and farthest from seats. He was heading back to his dorm in Yangpu District, about six kilometers away. Normally, he works as a welder on a site in Yangpu, but today his boss sent him downtown to help out.

He recalled a job last year in a protected heritage site downtown where there were no dorms. He and his coworkers stayed in an apartment two kilometers away. It was a half-hour walk or about ten minutes by metro. So he took the subway every day for two months. Talking about the recent harassment incident on Beijing’s Metro Line 5, he joked, “We’re all just laborers. If you’re so fancy, buy your own subway.”

Since there were no dorms on site, he always had to go home to shower.

During interviews, some workers told The Paper they’d love a simple changing room on-site. Right now, there’s no storage, so their water bottles, tools, and clean clothes get tossed in plastic bags and left on the ground, and end up covered in dust.

Even working in dusty, grimy conditions with nowhere to clean up, many workers do their best to stay clean and fight off stubborn dirt.

“Who doesn’t want to look a little cleaner?”

At 4 a.m. the day labor market was packed. Qi Jianjun parked his electric scooter by the road and leaned on a fence with other workers, eyes scanning for work vans. Slowly, workers climbed into vans heading to job sites. But as dawn broke, Qi still hadn’t been picked.

Early morning at the labor market

“Heading back to wash my clothes.” At 7 a.m., Qi Jianjun hopped on his electric scooter and headed back to his place. The building was a two-story house shared by over ten families. His room was on the ground floor, about 10 square meters, with its own bathroom. He pulled out his dirty work clothes from a shoulder bag tucked in the corner and showed them to the reporter.

Cement on Qi Jianjun’s pants

Cement hardens when it meets water, which is exactly what makes it such a staple in construction. But once it seeps into fabric as wet slurry and solidifies, it becomes a real nightmare to clean. The longer it stays, the harder it is to get out. That’s why the first thing Qi Jianjun usually does when he gets home is take a shower and scrub the cement off his clothes. On days when he’s too tired from working late, the dirty laundry just gets pushed to the next day, after all, he’s going to get messy again anyway.

Every season, Qi Jianjun buys himself two sets of work clothes online. In the summer, a T-shirt costs around six yuan, a pair of pants nine. Outside of work, he likes wearing bright colors like orange and pink, often paired with black leather shoes. But when it comes to workwear, he sticks to army green camo, dark purple, or black, along with safety shoes, all chosen to hide dirt. In the wardrobe at the foot of his bed, he folds and stacks his clothes into neat little squares, the contrast between his everyday outfits and work clothes clear at a glance.

Laundry on a construction site isn’t exactly convenient. Some sites do have washing machines, but according to Cao Daoyin, they usually charge by the minute: 4.5 yuan for twenty minutes. To save money, most workers just wash their clothes by hand.

Cao Daoyin lays nearly 1,300 bricks each day, starting at 7 in the morning and finishing around 5 in the afternoon. With that much contact, it’s no surprise his clothes are constantly brushing up against dust and cement. He often scrapes his knees while working, and there’s no clean place to rest on site. When his legs get sore, he just sits on a brick or a plank, which leaves the backs of his pants caked in dust. “We sit on whatever’s there. As long as you can lean on it, it works,” he says. On hot days, his clothes get soaked with sweat over and over again, leaving them sticky and unpleasant by the end of the shift.

“We change and wash every day,” says Cao. With all the dust in the air and the amount of sweat from working, even in winter, he says you need to wash your base layers at least every other day.

Jackets are a different matter. Workers say they don’t wash outerwear as often as T-shirts, sweatshirts, or pants. Jackets are harder to clean and take longer to dry. Washing them daily would mean buying extras to rotate through, which adds up. Except for the reflective vests provided on site, all work clothes throughout the year have to be bought by the workers themselves. These clothes are both necessary and disposable. Cao usually gets his from roadside stalls near the site. The quality isn’t great, and after a few months of heavy use and constant washing, they tend to fall apart and need replacing.

The real problem is that cement loves sticking to jackets. If they go unwashed for three or four days, the cement sets completely. Even with a stiff brush and a lot of effort, it’s almost impossible to get rid of those pale gray marks.

If jackets are a pain to wash, shoes are even worse. They get the closest to wet cement. Cao Daoyin and Wang Hui showed the shoes they just finished scrubbing. The textured soles and toes had been filled in by cement, making the details almost disappear. The uneven gray-white patches made them look like they were just been pulled out of the mud. But this, they said, was as clean as their shoes ever get. Wang Hui picked up one shoe, rubbed a gray spot along the edge with his fingers, then held his hand up to the reporter. Not a trace of dust.

Cao Daoyin (in army green camo) and Wang Hui (in gray and white) with their freshly scrubbed shoes

Not being able to sit down, not being able to get things clean, these are more than just everyday hassles. They’re part of the job and the environment that comes with it. A worker from Heilongjiang, when asked about a verbal harassment incident on Beijing’s subway Line 5, said, “Who wouldn’t want to look a little cleaner? But we just don’t have the conditions for it.”

The Longing for Dignity

Dignity doesn’t change based on your job. But for many construction workers, the dust, the fatigue, the lack of clean places to rest, the clothes soaked through with sweat, the patchy showers, and the cement that won’t wash out all combine into a daily battle. It’s what makes them the ones you see sitting on the curb, covered in dirt, worried about being looked down on.

Still, when it comes to physical discomfort, most workers just tough it out. They know that what matters more than appearances is getting paid.

Several workers brought up wage delays during interviews. Compared to how they could laugh off the tough work environment or the cement stains on their clothes, their tone changed completely when the topic shifted to unpaid wages. Their faces tightened, their voices rose, and frustration filled their words.

While waiting for his wages to be settled, Cao Daoyin counted his daily expenses on his fingers for the reporter. Just food cost him over 30 yuan a day. What really made him anxious was that the May Day holiday was approaching. Once the company closed for the holiday, it would be even harder to find anyone. All he could do was hope. He hoped the company would keep its promise to pay on April 30. But more than two weeks later, all he received was a handwritten IOU.

On May 9, with no pay in sight and turned away from a new job because he was nearly 60, Cao packed his things and went back to his hometown in Anhui. That’s where he had built his own house, one brick at a time.

Last August, just before a stretch of highway that Qi Jianjun had helped build opened to traffic, he posted a video of the wide new road on social media. His caption read, “This is the result of our hard work.” But even now, he still hasn’t received all the wages he was promised for that job.

In recent years, the government has rolled out policies to try to fix the problem of unpaid wages.

In May 2020, the State Council issued Regulations on Ensuring the Payment of Wages to Migrant Workers aimed at ensuring migrant workers get paid on time. It focused especially on the construction industry, requiring general contractors to pay workers first if subcontractors default, and then pursue legal reimbursement later.

In December of the same year, a national online platform went live for workers to report wage arrears. They can submit information through the site, and local labor inspection agencies will investigate any cases that meet the legal criteria.

In 2023, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security launched a nationwide campaign to set up fast-track courts for wage disputes involving migrant workers. Local governments were instructed to prioritize these cases and ensure they were handled quickly.

Getting paid for a day’s labor. That’s the dignity workers are truly hoping for.

The migrant workers are heroes. Here in Malaysia we have many migrant workers too. Our skyscrapers in Kuala Lumpur would not have been built without migrant workers. But in Malaysia we don’t usually have casual workers without permanent employment. I hardly see construction workers taking public transport.

Anyway, migrant workers are heroes. They leave their families behind to make life better for their children.

This made me cry. Thank you for sharing!