How Independent Bookstores in China Are Finding Ways to Survive — and Thrive

Blind-book boxes, revived out-of-print titles, and the quiet power of trust between booksellers and readers.

Good evening. Today I want to share a story about independent bookstores in China.

The original Chinese piece of this story was first published on Jan. 13 on the WeChat blog of Direct Connect (正面连接), an independent Chinese online media outlet that uses the tagline “Facing Complexity.” The article follows two independent bookstores — and the very practical question of how they stay alive — at a time when Chinese people’s lifestyles and reading habits are shifting fast.

Neither store survives by chasing bestsellers. Instead, they curate by taste: recommending books to subscribers based on their own aesthetic and intellectual judgment, building trust over time, and learning what their readers actually want. In some cases, that credibility gives them leverage to do what large publishers and mainstream channels often can’t: bring long out-of-print titles back to life, finding a second readership for “small” books that the market has already written off.

Subscription-based book clubs are hardly new. What is distinctive here is how independent booksellers, facing algorithms, price wars, and shrinking attention spans, reclaim selection as an editorial act. Their choices are shaped by long familiarity with readers, by personal conviction, and by a willingness to stand by books that might otherwise disappear. In this sense, selection itself becomes a form of authorship.

In the past, when the pieces I chose were especially long, I would sometimes shorten them before publishing, trimming sections without affecting the core argument. This time, however, I’ve decided to translate and publish the article in full. I believe that those who are genuinely interested will naturally make the time to keep reading.

For the independent bookstores and books mentioned in the piece, I’ve added their Chinese names alongside the translations, following the original text, in case some of you would like to seek out these bookstores in person or track down the books discussed in the article. Any highlighted passages reflect my own emphasis.

When you think about opening a bookstore, what is your first reaction?

If you start weighing investment against returns, chances are you would hesitate.

Most people agree on one thing: people need to read, and readers need bookstores. Bookstores — especially independent ones that do not sell exam-prep materials or “success studies” in China — are often seen as spiritual refuges for readers, but rarely as places of consumption. Those who commit themselves wholeheartedly to this line of work usually do so with the expectation of losses, or even eventual closure.

Yet new changes are also taking place. In Chengdu, Youxing Bookstore (有杏书店) closed and later reopened. In Wuhan, a year after Baicaoyuan (百草园书店) shut its doors, Sincerity & Authenticity (诚与真书店) emerged. In distant Guilin, Wild Mountain Bookstore (野山书店), run by a husband-and-wife team, surpassed one million yuan in monthly sales by selling only books on RedNote. And many other bookstores we can readily name — All Sages (万圣书店), Floating in the Wild (浮于野书店), Avant-Garde (先锋书店) — have also built thriving spaces within online communities.

Over the past year, amid an environment where low-price competition has reached its limits, we found that bookstores operating through RedNote e-commerce saw overall revenue growth of more than 30 percent, with nearly ten thousand brick-and-mortar bookstores collectively moving onto the platform. In this interest-driven community, buying books is no longer a purely price-centered commercial act. People are rediscovering what physical bookstores uniquely offer: breaking out of information cocoons, encountering an unexpected good book, and sharing it with those around them. Genuine and friendly relationships between people are also taking root here.

Curious about how all this has happened — how independent bookstores manage to survive and thrive, and what readers actually gain from them — we traveled to Guilin (a well-known tourist city in south China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region) and Wuhan (in central China’s Hubei Province) to meet the Wild Mountain couple and “Old Wang,” the owner of Sincerity & Authenticity.

“For the Encounter Between People and Books”

Wild Mountain Bookstore is located on a commercial street in Guilin’s High-Tech Zone.

The street is divided into an outer section, a middle section, and an inner section. The outer street is lined with restaurants doing street-front business and remains lively day and night. By the middle section, foot traffic has already thinned considerably. The bookstore sits near an entrance to the inner section, facing a residential compound and turning its back to pedestrian sightlines. Few people ever wander here by chance.

The location is hard to find. Reader Song Shuang still remembers the suddenness of spotting Wild Mountain for the first time. On a rainy night in August 2025, a driver dropped her near the compound. The navigation app was inaccurate. As she walked through the pitch-dark night, constantly looking left, she happened to turn her head to the right—and the warm yellow characters “Wild Mountain Bookstore” suddenly leapt into her view.

The reason she felt she had to visit the bookstore was simple: curiosity.

Even before coming, Song Shuang had come across posts by Wild Mountain on RedNote. In those posts, the bookstore owners—”Mountain Pig” and “Wild Rabbit”—shared how they had witnessed a new book being reprinted: in order to fulfill shipments for readers subscribed to their “Annual Reading Plan,” Wild Mountain snapped up the final remaining stock of the book. The Annual Reading Plan is a new product offered by the bookstore. Subscribers receive one carefully selected book each month, accompanied by a handwritten reading guide.

Song bought a book through RedNote, The Moss Forest (《苔藓森林》), which explores how moss grows and adapts in different natural environments. One of its translators is Wild Rabbit herself. What attracted Song was a line on the RedNote page: “From seeing the small, learn to love life.” Beyond buying the book, she also subscribed to Wild Mountain’s Annual Reading Plan.

Song studies history. Her usual reading habits closely follow her academic discipline—books on silk, opium, the history of the English language—digging deep into such narrowly defined perspectives.

But Wild Mountain’s Annual Reading Plan brought many other types of books into her hands. First came Transitional Labor (《过渡劳动》) and Higher Than the Mountains (《比山更高》), which sparked her interest in nonfiction and anthropology. In May, she received The Little Fox in My Head (《我脑袋里的小狐狸》), a picture-book story about bipolar disorder. Song had stopped reading picture books after high school, thinking they had “too few words to be interesting,” but this book made her realize that what picture books can carry is not limited by form.

Through Wild Mountain’s reading plan, Song felt she had gained a stretch of reading time outside her information cocoon. Without the couple’s recommendations, she would never have thought to search for a picture book about a little fox on her own.

At the very back of Wild Mountain Bookstore are two square tables for readers, with message notebooks placed on top.

These curated book lists — reflecting the owners’ personal aesthetics and deeply connected to the city’s cultural and humanistic fabric — are, for readers, “just-right blind boxes.” They are also precisely what gives independent bookstores their reason to exist. Song noticed that Wild Mountain carries almost no popular bestsellers. Most of the books are in the humanities and social sciences, and nearly all were published within the past year.

Both Wild Rabbit and Mountain Pig work in publishing. Mountain Pig approaches the bookstore with a product-design mindset. He wants to create a scene for buying books: at a time when people are so accustomed to goal-oriented online shopping, independent bookstore owners can, through bookstores infused with their own knowledge, experience, and care, offer readers a possibility — a possibility of discovering their true reading interests, of seeing lives beyond their immediate field of vision, and of re-encountering and reconnecting with others through the specific space of a bookstore.

In Wuhan, Old Wang has been running bookstores for thirteen years. A year after Baicaoyuan closed, he relocated and opened what is now Sincerity & Authenticity.

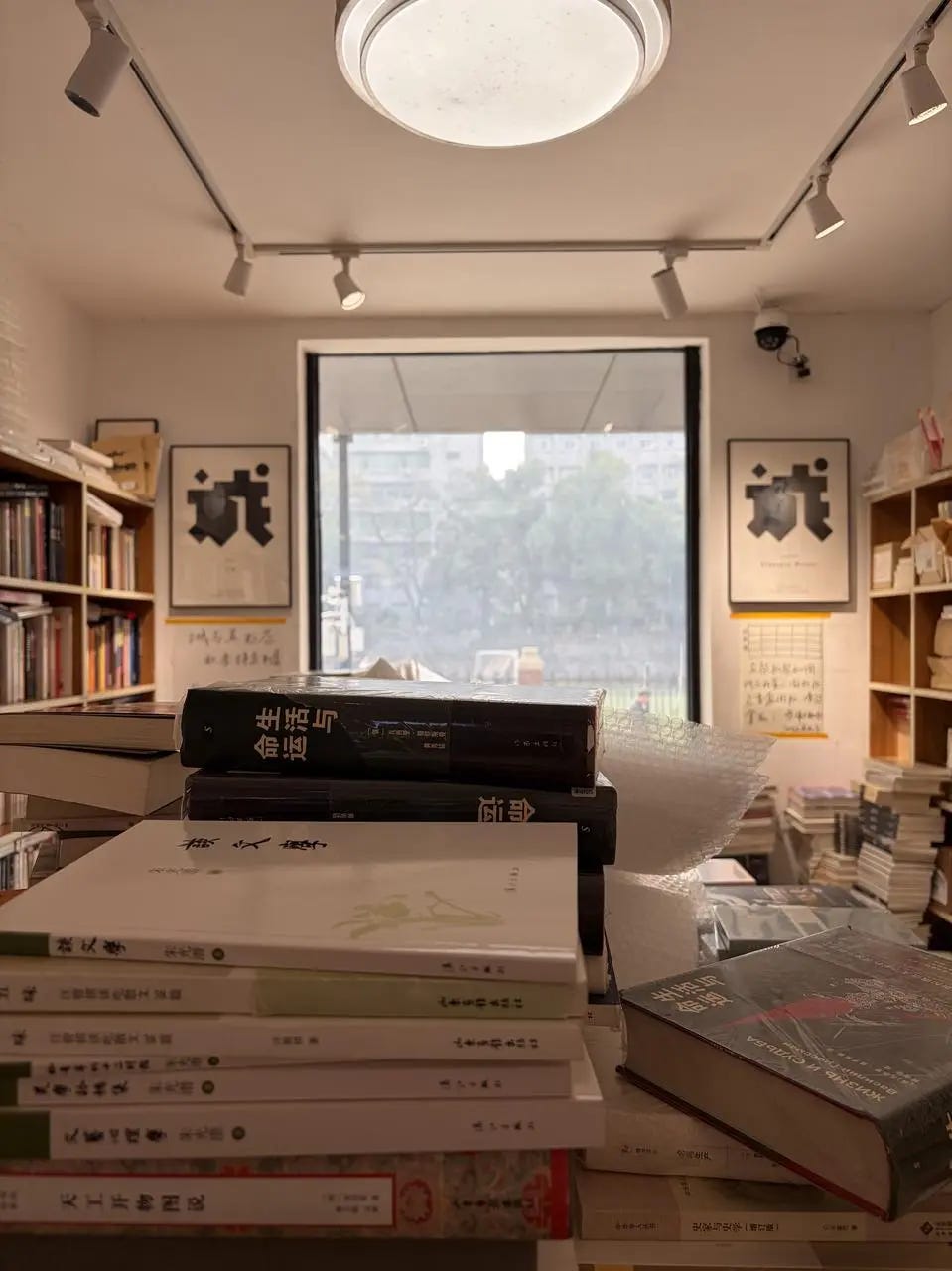

Old Wang has an exceptionally sharp eye for selecting and evaluating books. On the day I visited, an editor from a publishing house had come in person with new titles, specifically to thank him for the feedback he had offered. Many of the out-of-print books in the store were personally selected by Old Wang from publishers’ warehouses.

He knows that most readers who find their way to Sincerity & Authenticity already have strong reading preferences and clear expectations. What he wants to offer them is scarcity. One experiment is the “out-of-print book blind box”: every buyer can request one specific out-of-print title. Old Wang photographed all the out-of-print books in the store and uploaded them as a single image on RedNote—The Book of Snowy Mountains (《雪山之书》), A Roll Call of Modern Academic Circles (《现代学林点将录》), Burning the Boats (《焚舟纪》), and more. He then shows, during RedNote livestreams, how he assembles each blind box based on readers’ requests.

Perhaps only in RedNote livestreams can such a patient, slow atmosphere exist. There are no flash sales, no price slashing, no exaggerated performances. During the livestreams, Old Wang selects books, assembles packages, and answers questions. The blind-box purchase link sits quietly at the bottom of the screen while staff pack orders. Viewers are not just watching; they often offer suggestions for choosing books. A good livestream can sell over 20,000 yuan (about 2,870 U.S. dollars) worth of books; even a weaker one still brings in five or six thousand yuan.

Once, Old Wang received a blind-box order from a woman who provided almost no information about books, mentioning only her situation: newly married, and curious about Old Wang’s “first-instinct” recommendation.

He spent more than an hour selecting the book—the longest time he had ever spent on a single blind box. During the livestream, viewers suggested parenting books or titles about romantic relationships. Old Wang rejected them all. Why, he asked, would someone who has just gotten married and feels secure about marriage need a book telling her how to handle parenting or relationships? What he sensed was her happiness and ease.

The book still wasn’t decided. Some viewers urged him to “move on to the next one,” and Old Wang pleaded with the equally engaged audience: could he assemble it privately? The viewers refused—they insisted he make the choice on the spot.

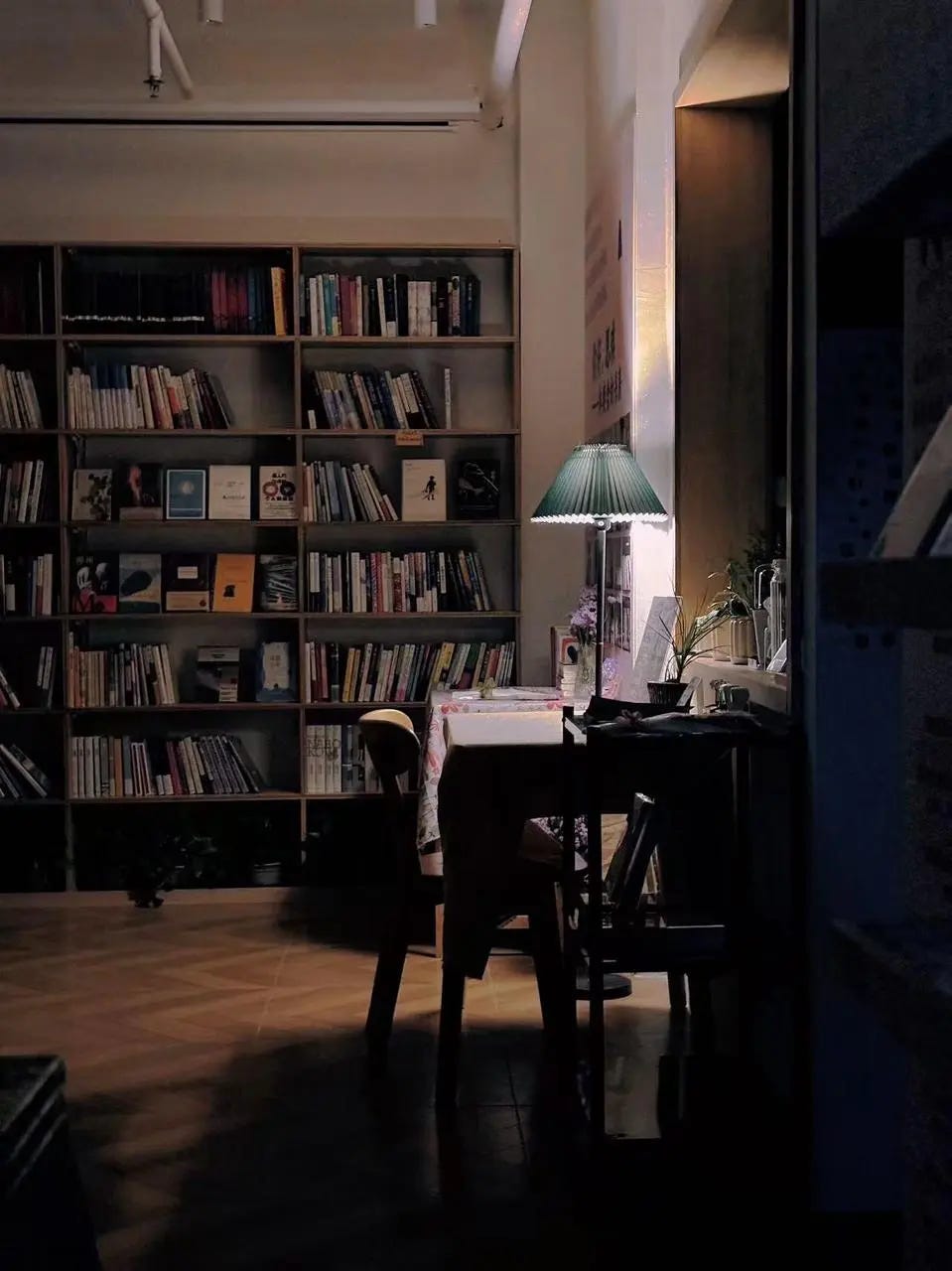

Reopening a bookstore seemed almost impulsive. About a year after Baicaoyuan closed, Old Wang was strolling through Tanhualin when he saw a shop for rent. He stepped inside and found that the layout was identical to Baicaoyuan’s old space. The rent was paid quickly. At first, green plants sat in front of the bookstore’s bright display windows, but soon more of Baicaoyuan’s style returned to Sincerity & Authenticity: too many books, stacked everywhere, so that when more readers arrived, they had to brush past one another constantly.

Inside Sincerity & Authenticity Bookstore

Why reopen a bookstore? I asked Old Wang. His answer was, “Because I have the resources for selecting books” — meaning that reopening felt natural. In earlier years, he had also said, “After the pandemic, Wuhan can’t be without an independent bookstore.” At that time, nearly all the independent bookstores of Baicaoyuan’s generation had already closed.

The Wild Mountain couple and Old Wang share a basic belief: people need to read, and readers need bookstores. Independent bookstores are a special kind of bookstore, usually run by long-term locals, with selections reflecting the owner’s personal taste. You typically won’t find school textbooks or prominently displayed bestsellers there. They may be seen as niche pilgrimage sites for literary youth, but rarely as places of consumption.

For this very reason, independent bookstore operators face a difficult reality. They must continually invent new models in response to rapidly changing lifestyles and reading habits to sustain the pleasure of reading. The Annual Reading Plans, blind boxes, and revived out-of-print books that Wild Mountain and Old Wang developed on RedNote are such experiments.

During the Baicaoyuan era, a line posted above the bookstore entrance read, “For the encounter between people and books.” At Sincerity & Authenticity, it became, “Sincerity & Authenticity embraces the book trade and reaches far.”

How to Survive?

In the first days after Wild Mountain opened, Wild Rabbit and Mountain Pig hosted events, including a screening of a documentary about Baicaoyuan’s closure. Some readers asked whether it was inauspicious. Mountain Pig replied, “Given our human limitations, closure is inevitable.” By this he meant that changes in independent bookstores are closely tied to the lives of their owners; any life change can affect the bookstore.

In reality, far more than personal life changes shape a bookstore’s survival: a city’s population size, number of universities, store location, and surrounding environment all matter. Baicaoyuan closed in 2021 because the landlord forcibly reclaimed the space.

In the months before closure, Baicaoyuan had its water and electricity cut off. Readers used phone flashlights to search for books. In the final days, someone approached Old Wang, asking him to serve as a book-selection consultant, calling him “talent.” Old Wang shot back, “Talent? What kind of talent runs a bookstore into the ground?” He wasn’t trying to snap at them; he was simply deeply dissatisfied with himself. As the owner, Baicaoyuan’s failure was his failure.

Yet this same Old Wang, who exited with embarrassment and bitterness, had already reopened Sincerity & Authenticity by the time Baicaoyuan’s closure documentary was screened at Wild Mountain. The bookstore’s name comes from the philosophy book Sincerity & Authenticity, which traces the evolution of the concept of the “self” across four hundred years of Western cultural history.

Old Wang is indeed a person of strong selfhood. When we met, he casually leaned against a pile of unopened books, constantly responding with questions of his own. In running a bookstore, he is ambitious and confident. Usually publishers choose bookstores to work with, but Old Wang also chooses publishers. For those who insist on selling books cheaply in their own livestreams while refusing to offer bookstores better terms, his view is simple: unnecessary. Bookstores are not begging publishers for business; as different actors in the same industry, they should enable one another.

Old Wang sits right in this aisle, assembling blind boxes for readers.

Indeed, when selling books becomes no different from selling any other product — when everything revolves around price — bookstores can no longer sell books.

In the publishing value chain, publishers, as upstream players, have gradually developed shelf-based e-commerce and livestream sales beyond offline channels. Today, virtually every publisher in China runs its own livestream. Bookstores, at the very bottom of the chain, have lost their original sales function.

They cannot obtain books at low prices from publishers because they struggle to achieve volume. As Old Wang explains, if a bookstore buys a book at a 40 percent discount, it must sell it at 80 percent of the list price just to make a profit. But in a publisher’s livestream, the same book may sell for 30 percent. “Readers aren’t stupid,” he says. “Why buy at 80 percent when you can get it for 30?”

Publishers are not deliberately targeting independent bookstores. The reality is that publishers have limited manpower, and the tiny quantities ordered by most independent bookstores are not worth the effort required to maintain relationships and offer low prices.

For independent bookstores to survive, they must gain bargaining power with publishers — that is, the ability to negotiate lower discounts. And to negotiate, they must achieve volume.

For Wild Mountain, the decisive factor in gaining bargaining power was the Annual Reading Plan launched on RedNote. In 2025, the plan sold more than 2,000 subscriptions; by the very beginning of 2026, it had already surpassed 5,000.

This means that over the course of a year, for twelve selected books, Wild Mountain can guarantee sales of more than 5,000 copies each. For most humanities and social science titles, initial print runs typically range from 4,000 to 5,000 copies to avoid unsold inventory.

Old Wang’s bargaining power is even more distinctive. It lies not only in volume, but in his confidence to sell niche books that others cannot. A philosophy book, On Certainty (《论确定性》), shows only 102 readers on Douban, China’s leading review platform. It was printed in 6,000 copies, failed to sell through e-commerce, and was returned to the publisher. Old Wang took it on and sold more than 800 copies.

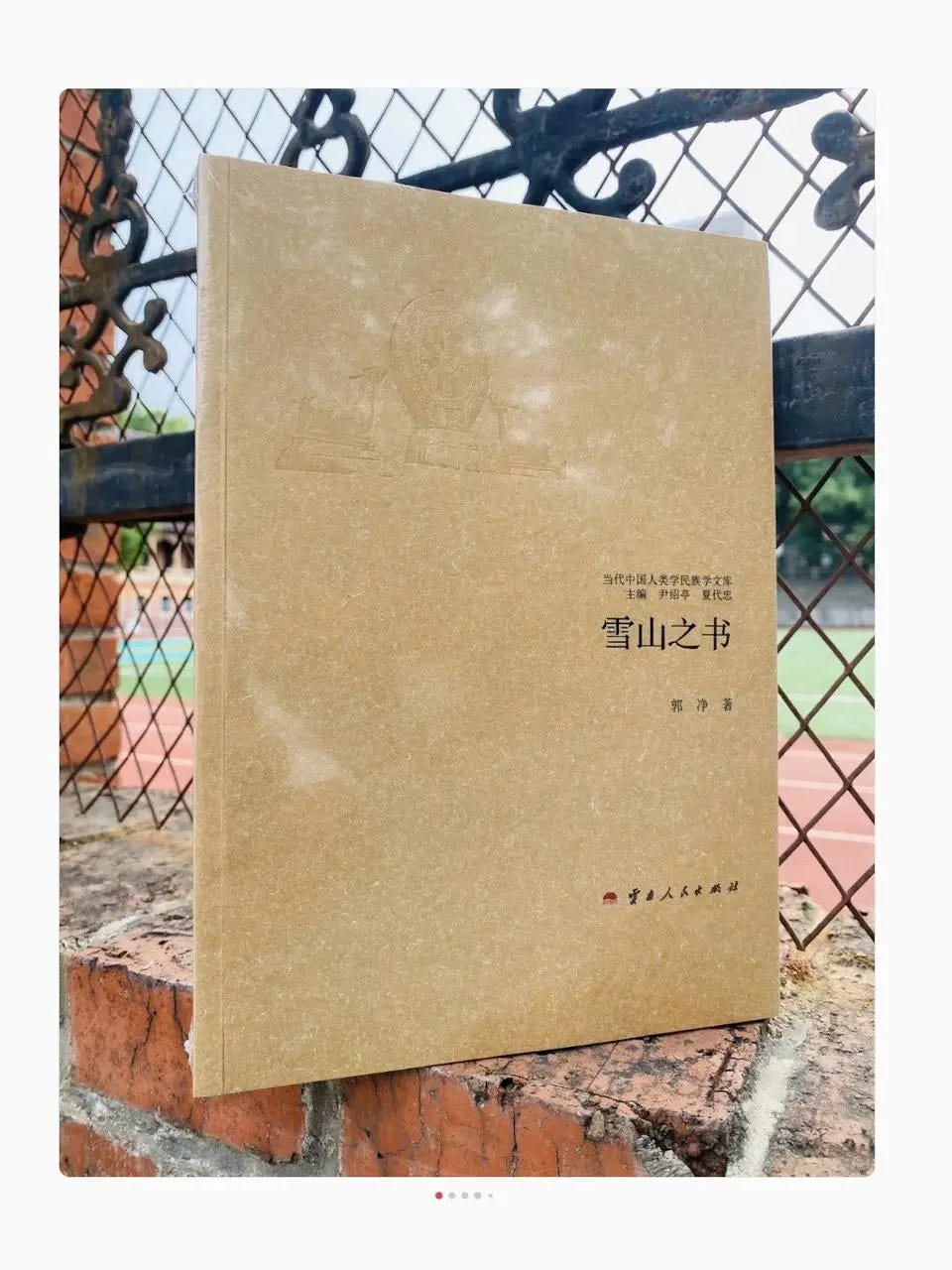

Moreover, among independent bookstores nationwide, Old Wang has a unique capability: reviving out-of-print books. He contacts publishers, advances funds, and buys out the reprinted inventory, relieving publishers of sales pressure. He then sells the books in his store. The Book of Snowy Mountains (《雪山之书》), an ethnographic study of Meili Snow Mountain by ethnologist Guo Jing, is one such example.

First printed in 2012 with 2,000 copies, The Book of Snowy Mountains soon went out of print. On second-hand platforms, its original 68-yuan price was inflated to nearly 300 yuan. Old Wang had his eye on it for seven or eight years. After repeated inquiries with no response, he called Yunnan People’s Publishing House again in May 2025. The distribution department said the book was old and needed to be discussed with editors. Over a month later, the reply came: it should be possible. Old Wang immediately asked when it could be printed — and waited again. The author needed to revise the text; editors had to proofread; internal procedures had to be followed. Another month passed before the contract was finally signed. In October, brand-new copies arrived at the bookstore’s door, and only then did Old Wang feel at ease.

To revive out-of-print books, Old Wang has invested more than one million yuan over time. His approach is simple: once the costs of one revived book are recovered, he moves on to revive the next.

Because of Sincerity & Authenticity, The Book of Snowy Mountains became a highly wished-for title on RedNote. In less than three months, Old Wang had recouped his costs. RedNote is the only platform he operates — he does not want to be merely a shop assistant listing books online, but to convey his understanding and feelings about each book.

The Book of Snowy Mountains

For Wild Mountain, the sales of the Annual Reading Plan mean the bookstore no longer needs to worry about mere survival. “A bookstore can make money” — this is what the couple wants to prove. What they now need to consider is scale: how big do they want the business to become?

Reading Is Contagious

One afternoon in late December, Old Wang and I were discussing details of The Book of Snowy Mountains inside Sincerity & Authenticity. An elderly man with gray hair stood nearby selecting books and listened for quite some time. When we paused, he stepped forward and asked, “Which book were you just talking about?”

Sincerity & Authenticity reminded me of the bookstore outside my middle school years ago. Back then, before smartphones, students in identical uniforms would weave past stacks of exam-prep books at the front and gather in the fiction and magazine sections. Some sat on the floor reading; others drifted along rows of spines.

Sometimes I was drawn to what others were reading; sometimes I simply wandered, deciding at random which book to open. Buying books then took time — it wasn’t about searching, ordering, and waiting for delivery, but felt more like a journey of discovering one’s interests.

The morning I went to Sincerity & Authenticity, I entered almost simultaneously with another middle-aged man. He stopped at every shelf. At one point he asked staff whether they had books on ancient architecture in Shanxi. Later, I noticed a book he placed on the counter—Chiang Kai-shek and Modern China (《蒋介石与现代中国》). I asked if I could take a look. It was the only unsealed copy in the store. He glanced at me and said, oddly, “Just flip through it.” As if my asking was unnecessary—of course one should read if one wants to, even if the book had already been bought.

After skimming a few pages, I asked staff to reserve a copy for me. This book would almost certainly never have appeared in my online browsing, nor would I have thought to search for it on any platform. But in the bookstore, like the gray-haired man earlier, I was infected by the interests of those around me. A few days later, on January 2, I returned to Sincerity & Authenticity—the store was so crowded it was hard even to open the door.

Two readers consulting staff at Sincerity & Authenticity about book selections

Compared with the bustle of Sincerity & Authenticity, Wild Mountain Bookstore — tucked deep within a commercial street — sees few visitors. Mountain Pig told me that only after opening did they realize bookstores also “depend on the weather.” When it is too hot or too cold, people don’t go out. If there are no other shopping areas nearby, readers are even less likely to make a special trip for a single bookstore.

Fortunately, Wild Mountain’s RedNote shop has several thousand Annual Reading Plan subscribers scattered across the country. Online communities partially recreate the reading atmosphere of physical stores, allowing interests to spread.

In the comments under Wild Mountain’s RedNote posts, hesitant users asking about the reading plan are often met with enthusiastic recommendations from other readers — covering shipping schedules, the surprise of receiving the books, and how precisely the selections resonate.

Now, Wild Mountain’s reading-plan shipments can fill an entire delivery truck.

In Wild Mountain’s online community, some local reading groups receive their books earlier each month, sparking “guess the title” games. Wild Rabbit shared the varied clues readers give: “The color scheme is red and blue,” “The title has eight characters,” “The author is French.” Remarkably, some people do manage to guess the title of newly released books from these hints.

Wild Rabbit wears straight bangs and round-framed glasses. She speaks gently, at an unhurried pace, with language that is polished but never pedantic—precise, direct, and clear in viewpoint. When we met, discussing academic books, she said, “Scholarship is starting to move toward accessibility. There’s really been more popular academic writing in recent years.”

Mountain Pig, with yellow-toned skin and black rectangular frames, speaks more quickly, but with few filler words or repetitions.

The Meaning of a Bookstore’s Existence

After opening a bookstore on RedNote, one of the Wild Mountain couple’s deepest realizations is this: reading can happen anywhere, and with anyone.

Among the shipping addresses left by readers, some are in villages the couple had never heard of; others read “on the cabinet of the fire brigade’s emergency supply box,” or hospitals, law firms, police stations. They call this the bookstore’s anthropological observation. “It’s incredible,” Wild Rabbit sighed.

An elderly man buying books at Wild Mountain Bookstore

“Pine Tree” is Wild Mountain’s third courier. In his thirties, with high cheekbones, he is usually quiet. Pine Tree is his WeChat nickname, and people call him that. He is meticulous: when he sees that parcels contain books, he stacks them neatly in woven bags to prevent damage. Staff member Yuhe and the couple therefore show him extra warmth—offering water and helping load packages.

Yuhe is enthusiastic and efficient, always animated when speaking. She often chats with Pine Tree. One afternoon, after he finished loading packages, Yuhe casually invited him: “Do you want to come by the bookstore after work tonight and read a bit?”

It was an invitation without expectations — Yuhe often made such offhand offers. To her surprise, Pine Tree actually came. Delighted, she rushed out from behind the counter and picked seven or eight of her favorite books for him. Pine Tree sat quietly at a small table in the corner and began reading.

About twenty minutes later, the couple arrived after receiving Yuhe’s message. After a brief discussion, Mountain Pig picked up Delivering Packages in Beijing (《我在北京送快递》) and wanted to give it to Pine Tree. Pine Tree immediately stood up, waving his hands in refusal. Mountain Pig persisted: “Take it! Books are meant to be read! We have so many here—it won’t hurt to take one!” Pine Tree continued to refuse, saying he didn’t read much and that it should be sold instead. Yuhe also tried to persuade him, but to no avail. So the three chatted around him: where he was from, why he worked for STO Express, and whether their deliveries were slower than others’.

Although Pine Tree did not accept the book, he read most of it and later shared his thoughts with Yuhe: it wasn’t quite like his own work, because the author handled individual consumer deliveries. Pine Tree splits his time between individual and commercial deliveries. He said he didn’t encounter “that many trivial hassles” in daily work.

More importantly, Yuhe emphasized to me that once Pine Tree began reading in the bookstore, “our relationship changed.” They were no longer just people coordinating work. After that, Pine Tree came to the bookstore roughly every two weeks. Before coming, he would always message Yuhe. He usually arrived around 8:30 p.m., stayed for an hour, and kept Yuhe company until closing.

At first, Pine Tree wandered among different shelves, but later he often stopped at the natural history section, flipping through books about plants. Yuhe described this reading preference as “special.”

One evening in April or May 2025, Yuhe handed him a book. Pine Tree took it and suddenly said, “Yuhe, I’m going to quit. I’m going home.”

Yuhe couldn’t believe it. After confirming several times, she finally asked what he planned to do back home.

His answer was even more unexpected: to grow sugar oranges.

Is April or May the season for planting sugar oranges? Yuhe didn’t know. In winter, when sugar oranges were about to come onto the market, she messaged Pine Tree to ask how his planting was going. A while later, he replied: “Still planting—almost done. I’ll send you photos when they bear fruit.”

Yuhe doesn’t know whether any of the natural history books Pine Tree read mentioned sugar oranges. But that no longer seemed to matter. By the time he began growing them, his WeChat nickname had changed from “Pine Tree” to “Carefree and at Ease.”

Munetaka Masuda, founder of Tsutaya Bookstore, once said, “Bookstores exist because of customers’ spiritual needs; profit is merely a natural result.” Innovations in setting and packaging are simply means of attraction. Understanding readers’ needs, inspiring the desire to share, and cultivating a space of ongoing exchange may well be the true core of independent bookstores’ success. Enditem

Thank you for this wonderful story!

Lovely piece