Is the valuation of Hong Kong stocks really that cheap?

“Trying to buy at the bottom of Hong Kong stocks and U.S.-listed Chinese stocks is essentially trying to buy at the bottom of the China-U.S. divide.”

[This post is contributed by red_wallstreet and edited by Ginger River. red_wallstreet, a friend of Ginger River, works in the financial industry and is not affiliated with Xinhua News Agency]

The following article was posted in Chinese on March 19 by 沧海一土狗 A Village Dog in a Vast Sea, a WeChat blog providing concise but often searing analysis of capital markets. As far as red_wallstreet understands, this blog was widely read by financial analysts and investors in China. In this post, which has been viewed more than 43,600 times, the author explained the reasoning behind the persistently cheap valuation of Hong Kong-listed stocks.

Introduction

When it comes to Hong Kong-listed stocks, many people have the impression that they are cheap, and this impression comes from the price differential between many A/H [dual] listed stocks.

Take ICBC for example. As of the close of business on March 18, 2022, its P/B for A股 mainland-listed A shares is 0.58 and for 港股 H shares it is 0.44 . The valuation of H shares is [thus] 24% cheaper than that of A shares [for the same company].

There are various arguments about this spread. Some say that it reflects the difference in liquidity between A shares and Hong Kong shares, with A shares being more liquid; others say that it reflects the different tax policies of A shares and Hong Kong shares.

In short, people can't make a sound argument even after half a day of bickering.

But this does not prevent people from forming a consensus: the low valuation of Hong Kong stocks is unreasonable, and we can take advantage of the valuation by going to buy on the cheap.

Stress test of the Russia-Ukraine conflict

The biggest shock in the recent month was the Russia-Ukraine conflict that broke out on February 24, 2022, which caused the Hong Kong's 恒生指数 Hang Seng Index to fall 22.17% between February 24 and March 15.

In fact, Hong Kong stocks have been reacting since the U.S. government repeatedly warned everyone that Russia was going to invade Ukraine.

U.S. President Joe Biden said on Feb. 18, in response to questions from reporters, that he was confident that Russian President Vladimir Putin has "made the decision" [to invade Ukraine] and that this judgment was based on U.S. "intelligence capabilities." Then, the Hang Seng Index fell 4.57% from Feb. 18 to Feb. 23.

So the Hang Seng Index has been reacting to geopolitical risks in lockstep. From Biden's warning to the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine incident, to the sanctions on Russia by Western countries, to the big reversal after the Financial Stability Board's statement.

So why do Hong Kong stocks react to geopolitical risks? This is because the companies in Hong Kong stocks are Chinese companies, but the denomination currency is the U.S. dollar (ps: the Hong Kong dollar is strongly pegged to the U.S. dollar).

Different positions, different perspectives

As a mainland investor, it is difficult to perceive the subtleties of this institutional arrangement.

So, let's switch our identities and pretend we are an American investors.

There are two different ways for U.S. investors to invest in mainland companies: 1) buy Hong Kong stocks or 中概股 U.S.-listed Chinese stocks; 2) exchange currency [into the Chinese currency renminbi (RMB)] to buy A-shares.

On the surface, the difference between these two types of investment is simply where the company is listed. In fact, it is not. The core difference lies in the way sovereign credit risk is embedded.

For U.S. investors, the Hong Kong stock valuation is a 混合估值 hybrid valuation, which includes both sovereign credit risk and corporate valuation, while the A-share valuation is a pure corporate valuation, where sovereign credit risk is taken up by the RMB.

So, for U.S. investors, the valuation of Hong Kong stocks should be cheaper than A-shares because of the embedded sovereign credit risk.

It is not hard to explain why Hong Kong stocks reacted to geopolitical risk and followed the evolution of the Russia-Ukraine story.

When Russia was sanctioned by the West, all overseas investors would turn their attention to China-U.S. relations. Until this higher-order issue is clarified, people are afraid to buy at the dip.

The contagion of this sentiment is similar to the contagion of credit risk. When Yongcheng Coal had problems back then, the valuation of other coal companies also came under substantial pressure and required [country's] leaders to come out with support; when Evergrande had problems, the valuation of other real estate companies also fell rapidly.

However, it is difficult for mainland investors to think in the perspective of foreigners. First of all, we are naturally bound to this big ship [of China], and there is nothing to debate here as we share her prosperity and loss together. Secondly, we sincerely feel that China is developing well, so what is there to question? So, we have consciously or unconsciously left out sovereign credit risk & geopolitical risk.

From the eyes of foreign investors [however], sovereign credit risk must be considered, and the valuation of Hong Kong stocks must be lower than that of A-shares, while for mainland investors who are oblivious to country-specific risks, they can't stop to feel that for the same high-quality domestic enterprises, Hong Kong stocks give an attractive valuation.

These are different perspectives, resulting from different positions of standing.

Low-order perspective and high-order perspective

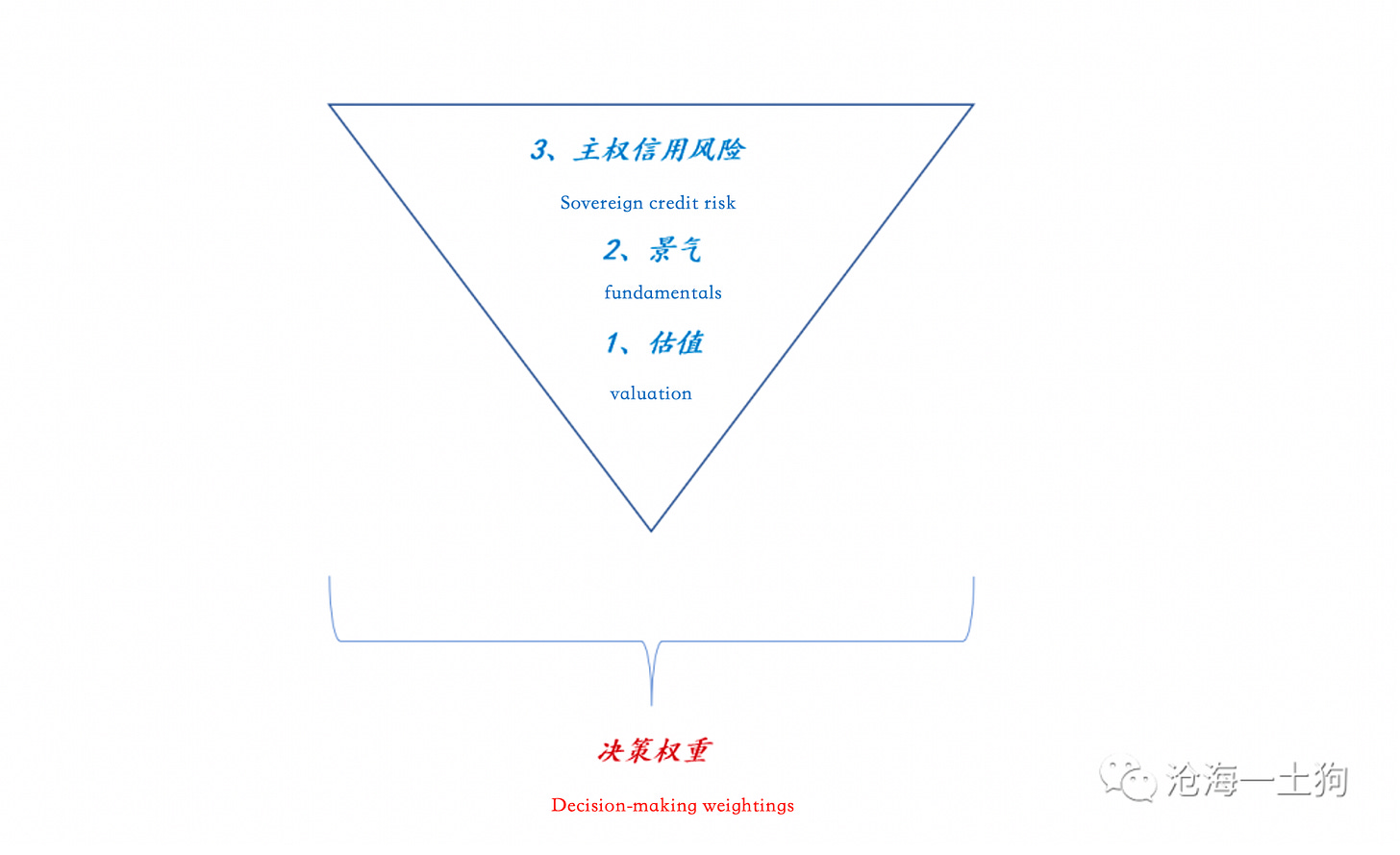

In the article "How to properly view the valuation logic of bank stocks - a credit risk perspective"(Chinese), we emphasized that valuation, fundamentals and credit risk are three levels of perspective, with valuation at the lowest order. It is very undesirable to invest simply by looking at cheap valuation.

Before going to buy something based on cheapness, think clearly about two higher order issues.

1. Will credit risk be a problem?

2. Will fundamentals improve?

There is a similar problem for cross-border investments, with sovereign credit risk being the highest order perspective, followed by fundamentals, and finally valuation.

A reasonable decision making system should give higher weight to higher order variables.

In fact, the market also prices the underlying asset according to the decision pyramid in the figure below.

On the [myth] of "taking over pricing power" (定价权争夺)

[Ginger River notes: going over to Hong Kong and take over the pricing power is a commonly used battle cry for many domestic investors]

Many domestic investors are not convinced by the low valuation of Hong Kong stocks.

They reasoned that the Hong Kong market is a foreign-dominated market, so the pricing power is in the hands of overseas investors, and the pricing model will follow the foreign perspective; however, if there is a massive influx of domestic capital into Hong Kong stocks, the pricing model will follow the domestic perspective.

The ideal is beautiful, but this is actually an unrealistic fantasy.

Even if there are domestic institutions left in Hong Kong stocks, eventually everyone will follow the existing rules of the game.

Why is this? Because not playing according to the existing rules will leave a huge space for arbitrage.

On the surface, the problem of Hong Kong stocks is a problem of domestic and foreign investors competing for pricing power, but essentially it is a problem of arbitrage direction - domestic investors want to arbitrage from lower-order perspective to higher-order.

However, profitable arbitrage exists only from higher to lower orders, not from lower to higher orders.

Take the ruble and RMB money market arbitrage as an example: after the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the Russian interbank overnight interest rate soared to 20% and the RMB overnight interest rate was at 2%, with a huge spread between 2 and 20, there was a huge opportunity for lower-order arbitrage.

On the surface, it looks like a perfect arbitrage business to exchange a sum of RMB funds into rubles and roll it to the Russian interbank overnight for a year to earn 18%.

But this is just an idea based on lower-order logic, which ignores the huge sovereign credit risk premium. Whether the 18% can be earned depends on the ruble's exchange rate, and if the ruble depreciates by another 18%, it amounts to nothing.

Can exuberant nationalist sentiment counters cold calculations of profit? Suppose again there is a Russian living in Russia, who has a huge deposit in RMB. He loves his motherland very much and feels that the 20% pricing is unreasonable, so he decides to sell a swap: a 2% RMB repo against a 10% ruble repo.

It's not hard to imagine the consequences: a huge arbitrage would quickly snap up his big pile of RMB money in one fell swoop. In the end, the Russian interbank overnight rate stays at 20%.

So, arbitrage based on lower-order logic is always dangerous and easily beaten to death by higher-order risks.

Unfortunately, it is often easy to see only the lower-order opportunities and risks.

Conclusion

In fact, Hong Kong stocks already priced in a round of higher-order risk during the U.S.-China trade friction [in 2018-2019]. The reason why that round was not felt so strongly was because the A-shares also performed very badly at that time, and Hong Kong stocks did not show extra volatility as this round.

But for foreign investors who hold the pricing power, they already traded around the [same] geopolitical logic at that time. This time they are simply following the same script.

Mainland investors cannot be blinded by their position, seeing only the cheap valuation of Hong Kong stocks and not the geopolitical risk discount embedded in them.

Therefore, when [you] buy Hong Kong stocks or Chinese stocks, [you] buy at least two things.

1. The China-U.S. relations.

2. Fundamentals of industry or business.

Fortunately, the heads of China and the United States have spoken on the phone on March 18. Plus, the Russia-Ukraine incident seems to be nearing its end. So the odds are that this storm is over.

This huge shakeout helped us to thoroughly probe what the deeper pricing mechanism of Hong Kong stocks really is - the China-U.S. relations and the China-U.S divergence. Trying to buy at the bottom of Hong Kong stocks and U.S.-listed Chinese stocks is essentially trying to buy at the bottom of the China-U.S. divide.

To be honest, the market is really efficient. (Enditem)

***

To help make Ginger River Review sustainable, please consider buy me a coffee or pay me via Paypal. Thank you for your support!