New beginnings: A county mother’s move to Shanghai with her daughter

Two shapes in two Shanghais

Good evening!

China's unprecedented urbanization over the past several decades stands as the largest in human history, unfolding at a remarkable pace. Recent reform resolutions emphasize the critical role of integrating urban and rural development in China’s path to modernization -- a top priority on the political agenda. Last month, this vision was further detailed in a State Council's five-year action plan focusing on a people-centered new urbanization strategy.

While stories of young Chinese professionals flocking to megacities are commonplace, the experiences of Chinese parents who move to these urban centers to be with their children present a unique narrative. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China is poised to see 20 million retirees annually between 2022 and 2032. Many women, born in the 1960s and 1970s, are now entering retirement, and many of them choose to either relocate to cities where their children work or shuttle between their hometowns and these urban areas.

Today’s feature delves into the life of Amin, who, at 53, retired and moved to Shanghai to live with her daughter, Song'er. While Amin’s story may not represent all Chinese parents who migrate to big cities, it captures a generational narrative of adapting to rapid societal changes, managing relationships with differently minded family members, and rediscovering oneself. This theme was also touched upon in Robert Wu’s newsletter China Translated.

This also points to one of the key difficulties in understanding China that I talked about many times: because China’s modernization has happened so fast, too many very different generations are crammed into the space of less than a century. For example, my grandparents’ generation was born in a countryside whose cultural contours were not much different from the Qing Dynasty’s peasantry. my parents’ generation was born into Maoist poverty. My generation was arguably the nexus between the generations older and younger, and we sort-of have a taste of everything. We played video games as children, but witnessed the attitudes and ways of life of all previous generations. Now is when the 00s, who grew up smartphones and social media, came into adulthood. But the fact is, all of these very different generations co-exist under the same roof.

Originally titled "妈妈的悠长假期 Mom’s Long Vacation," the story was first published on the WeChat blog of “极昼工作室 The Midnight Sun Workshop” in July. To enhance readability, we have made thoughtful edits to the original, lengthy narrative.

Mom’s Long Vacation 妈妈的悠长假期

When she retired from a civil service job at a county (equivalents of districts within a Chinese city), Amin, 53, moved from Quanzhou, in southeastern China’s Fujian Province, to Shanghai, where her daughter Song’er works. Trying to adapt to a new life, she had many firsts: she auditioned for a clothing store model on the shopping app Taobao, worked at a school canteen, went to plays and talk shows, attended a concert of LiSA, and got hit on by an old guy. “Shanghai is not so great after all.” She shared with her friends back home.

Song’er likened her mother to a non-playable character (NPC) in video games, her life going like clockwork. Amin spent the past three decades working at a library back in Fujian. Her life was meticulously structured. The bathroom was forever clean. Meals were forever prepared. She was that NPC who did everything in some back corner unseen on videogame screens.

Amin is just one among many Chinese women born in the 1960s and 1970s entering the latter phrase of life in the biggest wave of retirement China has seen. Between 2022 and 2032, the number of Chinese retirees is expected to reach 20 million each year, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. Many female retirees, like Amin, choose to leave their hometown and live in the city where their children work.

Now living with her mother again, Song’er attentively reads Amin’s world. Below is an excerpt from her observations.

Two Shanghais

The day before leaving for Shanghai, my mom regretted that she could not pack her home and bring it there. In her luggage were things, from mung bean cakes and freshly cooked meals, to a rice cooker, an induction cooker, and even another pressure cooker. I couldn’t understand why. She had her reason, “I need them to be able to cook.”

My mom has her own way of cooking. She boils everything in water without condiments. If there is any color in the dishes, it must be the brown soy sauce. Even in Shanghai, she is still the one in charge in the kitchen. She insisted on her old and familiar cooking things. That included the pressure cooker, the bottom of which has turned a caramel yellow, after more than ten years. But she said it cooks quickly. Every time she returns from Quanzhou, she would bring along local specialties, like sweet potatoes, oysters, and razor clams, which she uses to make oyster omelets, staple food back home. She wants to carry her home to Shanghai.

At first, we lived in a dilapidated building in Yangpu. We rented an apartment with an attic, for a monthly rent of 3,700 yuan (about 516 U.S. dollars). The wooden stairs creaked with each step we took, and the wires at the corner were a haphazard heap. Our heads got bumped easily, even with our less-than-1.5-meters heights. I chose that apartment with an attic, because I wanted privacy, yet I still ended up roommates with my mom. She took the bed, while I made a makeshift one on the floor. The attic? We repurposed it into a storage room.

Every morning, mom just waited there, keeping an eye on me. As soon as I showed signs of leaving for work, she suddenly changed her attire, timing it perfectly to head downstairs together. Once outside, we went separate ways. I would hop onto my electric bike to the office, while she would take a shortcut to the outdoor food market, on a second-hand bike she bought after moving to Shanghai.

She used to be a librarian. She had short hair and always wore bright-colored clothes, like a red vest. She looked busy and indeed was so. She arranged magazines, coded them, and cleaned the floor. Now that she’s retired, she has been looking for a new routine to re-structure her life.

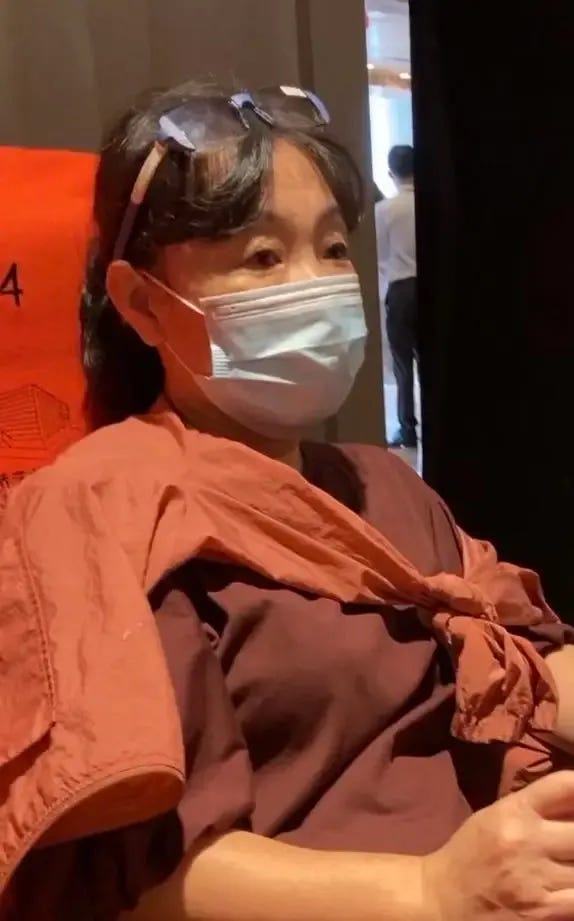

Song'er takes a picture of Amin, on her way to see a play for the first time in Shanghai. All photos credit to Song'er

Some modern facilities in Shanghai scare my mom. For example, she almost fell down on the escalator several times; she couldn’t scan a QR code on her mobile phone at the subway entrance, so I had to scan it for her from the other side of the ticket gate. After living in Shanghai for about three or four months, she began a job hunt. She downloaded common recruiting apps like Boss Zhipin, Jinri Toutiao, and 58.com. Wearing her reading glasses, she meticulously searched through the listings every single day. Many positions do not hire anyone over thirty-five, let alone over fifty. The only jobs she seems to qualify for are either a canteen worker or a cleaner.

One day, she found an agency seeking middle-aged and elderly part-time models for online shopping stores on Taobao. I accompanied her to a job interview at an office building in Wujiaochang. She put on a dress, applied a heavy layer of foundation, shaped her eyebrows and drew her eyeliners. She was much more alive and quite excited on the way there.

We got to a very small studio. Three or four applicants were already there, clearly high school or college students, with “not yet graduated” nearly written on their faces. When it was mom’s turn, a middle-aged man asked us who was applying. I pointed at mom. He gave a glance and let us in. The interviewer asked her to do a few photo shoots and send the pictures.

To take the photos, I let mom wear my clothes: a Hong-Kong-style leather jacket for summers, with black overalls. I was overcome by a peculiar sensation at that moment. It was as if she was not my mother, but just a woman I met somewhere. We chose to take photos among the bushes downstairs, spending a long time posing. In the end, we managed to get a lot of photos, and also a lot of mosquito bumps.

We sent the photos, and never heard from them again. However, mom didn’t give up. Somehow, she found a job at the canteen of High School Affiliated to Fudan University, serving food to the students. She went to work before I woke up; at night, she’d come home and complain about the tiring job and her harsh manager. She wanted to give the students more food, yet the manager didn’t allow it, and scolded her for working too slow.

My dad did not approve of the job, as he was prejudiced against manual workers. He would phone my mom at a fixed hour every night. She was worried that he might find out, because she didn’t finish work until nine or ten at night. She was afraid and didn’t know whether she should continue, because my dad has been the decision maker in the family. I told her, “Dad isn’t here; he can’t control you.” I also had my own motive: I wanted her to experience the cruelty of the world outside civil service jobs.

My mom and I both live in Shanghai, although not the same one. I live in a young, modern Shanghai, where everyone is always at running speed, either hurrying to work or rushing to meetings. We go to talk shows teasing the workplace, play script games with the younger crowd, and rely on smartphones for navigation.

My mom belongs to an elderly, less privileged community of migrant workers predominant in Yangpu. Not many Shanghainese lived there. She watched the elderly in our neighborhood chat and play cards, and came to join them. One day, I noticed the cleaning lady in our office building wearing her hair in a low bun, like mom often does. She would also keep her bangs neatly combed and tie a tight bun at the nape of her neck. As I watched the cleaning lady, I couldn’t help but think about mom in the canteen.

Her canteen job didn’t last long. One month later, she accidentally burnt her hand with the cast iron skillet bibimbap. Then she decided to quit her job. It was the first time she wrote a resignation letter. She found a template online, changed the name to hers, and asked me to double check. Not long after, I experienced a different kind of harshness: the layoff lottery.

There were only two versions of the office story: those who frantically worked overtime, and those who disappeared from the office without a trace. I wasn’t on the list, but a senior colleague who had trained me left. She taught me a lot when I first came here. That was when I first realized how profit-driven a company could be.

Tomatoes: sei ang ki or fan ga?

Mom is most familiar with the outdoor food market in Shanghai. She goes there almost every day. At first, she always compared the prices between Shanghai and Quanzhou, our hometown. She had never seen so many kinds of tomatoes, with prices ranging from 2.5 yuan to 12 yuan. She thought that average prices are pretty much the same, before those in Shanghai doubled as the Spring Festival approached. Every day she lamented that things became more expensive and money gone faster.

She compared everything here with those back home. “The dried sweet potatoes are not as tasty as what we have at home; and the streets here aren’t so bustling after all.” Her besties back home live a more settled life, either collecting rents or taking care of grandkids. She could have collected rent at home, but ended up living in a rented apartment in Shanghai. She always phones them over WeChat. “Home is best! Shanghai isn’t so great.” She repeats.

I’ve tried to draw her into the younger Shanghai. I took her to a play by the comedy troupe Mahua FunAge, and a talk show at the Er Sansan comedy club. On our way home, I asked her how it was. She still compared the show with those back home. “You know, I also go to plays back home, Ko-kah-hìs (a traditional form of theatre that originated in Fujian) and puppet shows.”

In early June 2022, after finishing my postgraduate studies, I found a job at an internet company in Shanghai. That was also the year my mom retired. I’m an only daughter, so my parents decided that mom would move in with me.

The first thing she did in Shanghai was to pray in the temple for blessings. She did the same when we moved. I didn’t know that she remained awake for hours at night when I slept. She just kept things to herself.

She found it hard getting used to rhythms in a big city. After all, she had spent the first 50 years of her life in a little provincial town. She seldom asked for a leave and rarely travelled out of the province. On our way driving to Xiamen, a major city in Fujian, we pass the streets though which she used to go to work. She would point out where the streets led, adding that she had walked them hundreds of times when she was younger. In my memory, that was the farthest place she had been to.

My mom lost her job at the grain station during the massive layoffs, when China’s state-owned companies were restructured in the late 1990s. Later, she recommended herself to the library post. My mom tried hard to take control of her own life, from her job to her spouse. She is the second child, with an elder brother and a younger sister. At the age of 16, she was denied school and started working at the grain station to sell rice, handing over her wages to support the family. She met my dad through an arranged blind date. She knew early on that more money would be spent on her elder brother, so marriage could be more or less a means to help her achieve relative financial independence.

As far as I can recall, mom’s world revolved around our family. When I returned home from school at noon, she was always in the kitchen, her back towards me. She was either processing the food or cooking, or doing the dishes and tidying up the table. Sometimes, she would go out, yet her only entertainment was playing cards in the home of one of her besties.

She has the busy routine of an NPC, a clockwork side character in video games. She did all sorts of tasks in a hidden part of the game that players cannot see. The bathroom was always spotless. “The cleanliness of a bathroom shows whether the lady of the house is lazy,” she said.

The Shanghai apartment rented by Song'er and Amin.

In Shanghai, she also does chores, but she’s also becoming the center of her own life. She would buy affordable items online and decorate her apartment with them, from the small fan in the kitchen, the 200-yuan drone (which I returned), to the tent and the sleeping bag. She said the sleeping bag makes her feel warmer in winter, and suggested that I join her. She’s looking for another life in a totally new place, like a video game player who’s leveling up.

My mom got to know many of our neighbors through her frequent visits to outdoor food market. An elderly lady in her fifties from Jiangxi (a province adjacent to Fujian) used to live upstairs, working as a cleaner in Shanghai. They visited the botanical garden together, and she taught my mom how to get to the Hongqiao Railway Station faster. One summer, she moved away and left us some furniture. That was the first time my mom experienced goodbye in a big city. I could sense her sadness. “She might never come back,” she said.

One year later, we moved to a new, larger neighborhood with more settled residents. Different from where we used to live, here even windows on the second floor do not have anti-theft bars. In this new place, my mom started another life. She took part in community events, taking video editing lessons and watching movies. She also started learning Shanghainese, repeating names of vegetables to herself every morning. In Quanzhou, corn is yomi, and tomato is sei ang ki, but now she says tsentsymi and fan ga in Shanghai.

Mom has integrated into the neighborhood better than I did, more familiar with places in Shanghai. I have to use an online map, while she could directly tell me which bus I should take, to go there faster than the route on the app.

One Early Morning

After living in Shanghai for a year, my mom returned to Quanzhou, to take care of her own mom. While staying with my grandmother, she always, consciously or unconsciously, expressed her preference for Shanghai. This year she came back to Shanghai after my grandmother passed away. Being curious, I had a conversation with her one morning over breakfast.

I: Mom, you’ve been in Shanghai for more than a year. Do you have a sense of belonging here?

Mom: Not so much. For me, a sense of belonging comes with having a room of one’s own, but not so when you rent that apartment instead of owning it. I’ve also seen things around me. To be honest, I don’t think Shanghai has made any progress in the past two decades. The spaces are too narrow, and life quality is better in Quanzhou. At first, I thought I could make friends with the Shanghainese, and I’d never thought I would only know middle-aged and elderly migrant workers in Yangpu. The Shanghainese don’t like chatting with people from other places, and they don’t want to speak Mandarin. Why am I learning the dialect? Because I want to understand them and engage with them. Otherwise, I’d have nothing to say. That is not a nice feeling.

I: Have you noticed any changes in me after you moved in?

Mom: We have not talked much, since your sophomore year. Now you are lazier. You’ve got used to the taste of takeaways, and you don’t like what I cook. This is quite immature. I know, you live in another world, different from mine. There is a generational gap between us, so you feel you can’t connect with me. Also, I hope that you could make the most of your time and prepare for the civil servant examination. The job you’re doing now comes with its pros and cons on both sides. So many people lost their job right after the COVID-19 pandemic. I’m afraid you might lose your job at any time. I think I’ve given you enough time to explore life, and it’s time for you to refocus on your studies and exams.

I: So you mean after two years of my career, you still think I should “get back on track” and take the civil servant exam, right?

Mom: Yes. Become a civil servant or anything with a stable bianzhi in the public service system. After all, competition is intense here, with so many hyper-educated people. These years, it’s all about diplomas in the job market. Of course, you should also find a boyfriend to go steady with. That’s top priority.

Two Persons in Different “Shapes”

I couldn’t help but question my mom, every time she suggests that I prepare for the civil servant examination or go on an arranged blind date. She asks everyone she knows to set me up on blind dates, worried that I would no longer be of eligible age after a few years. She even went to the famous matchmaking corner at People’s Park. One day, I went there with her. I saw a pile of notes laid out on the ground, with specific criteria for a life partner written on each. Mom checked them one by one. Sometimes people thought she herself was there for a blind date. A man said she is very attractive and asked if her husband is still around, offering to introduce her to someone if she is single. She told that to my dad, seeming a bit proud.

From her, I saw an earlier reflection of myself adapting to big city life when I first arrived. About two weeks ago, I took her to a concert of LiSA, a Japanese singer. She joined the crowd, waving light sticks and cheering aloud. She told me she wanted to have a drink when we got back, or she would be too excited to sleep.

Amin at the 2024 Spring Festival Lantern Show in Quanzhou, Fujian.

One night, I was looking into the mirror in the bathroom when she passed by. I asked her to join me, but she refused. I couldn’t understand it and asked why. She replied, “I’m so old; you’re so young. I’m jealous.”

That was when I started taking the time to observe my mom and reflect on our relationship. I once read a book by a Nordic writer on her relationship with her mother. “I think mom is often jealous of me. I have a talent, I write well, and I’m young too.” She wrote. I also recall Autumn Sonata, an Ingmar Bergman film. Bergman had wanted to portray an ideal reconciliation between the mother and daughter, yet it was impossible. They fell into a bitter argument on a stormy night, before pouring out their pasts to one another.

It occurred to me that I’d been looking at mom through a narrow lens. I had only seen her as a mother, not as a woman. I should focus more on the woman aspect.

When I was young, it was her responsibility to take care of me. I still remember some of the moments we spent together. She took me to the library by bike; I read her the fairy tales I wrote. Worried about my height, she asked everyone for advice. She took me to an aged practitioner of traditional Chinese medicine, who gave black herbal pills. She also enrolled me in swimming lessons. Neither worked. I am no taller than she is.

I began sleeping on a single bed in my early teens. Later she suggested that we still share a bed. No, no! I said. “Why does Mom ask me again and again?” I wrote in my diary, “It’s not because she’s suddenly realized I still need her hug; it’s just that she’s not used to being alone herself.” Mom is insecure. No one, including me, has been willing to offer her the emotional support she needs.

When I went to university in Beijing, I got farther away from her. I was busy with different things. I was afraid to tell my parents about going to LGBTQ+ offline meetups. By the time I came back home for summer after my freshman year, my taste buds had adapted to Beijing flavors , and I no longer felt good with mom’s style of cooking, boiling everything in water. She started calling me “阿北子” (Abeizi), meaning a non-local in Quanzhou dialect .

For about six to seven years, I metamorphosed into another shape, completely different from hers. Years of living apart only highlighted gaps between us. Our biggest conflicts are about the civil service exams and arranged dates. She’s often had some sort of expectation for me, with seldom any laid-back, stress-free moments. Our relationship has long been shadowed by responsibility and demand.

When I was a “school kiddo”, she was the mother worried about my academic performance. In her bedside drawer, she keeps my school report cards throughout middle school. They are still there, frayed with age. She would carefully analyze my grade fluctuations and hire tutors to help me with math, physics, and chemistry.

Now I’m a “job person”, and she is the mother who wants me to integrate into society in her way. She thinks taking the civil servant exam is the correct and expected path for me. If I had an interview the next day, she would be so worried that she couldn’t sleep well at night.

Last September, I attended my grandmother’s funeral. One evening, we took the time to burn some of the clothes she had worn during her lifetime. I discovered that grandmom had bought many brightly colored clothes in the last one or two years before she died, though she rarely wore them in front of us. She simply stored them in a neat place. It was then that I pictured someone new in my head, who had her own taste for these clothes. Still, the four wreaths at her funeral came from her husband, her son, her high school friends, and where her son works. She is talked about as a mother or a grandmother, and we are family members. We talk about mom in the same way, someone in an extended family.

If there were cherished moments in our relationship that I wish I could go back to, they would be the Sunday afternoon naps we took together, when I was nine or ten. Sometimes we’d sleep from noon till four. One day, we slept for four hours straight again. “I can’t believe it’s already four!” She exclaimed. However, she didn’t get up, just lying in bed. That was a rare moment of her sleeping in, indulging in the comfort. I really miss the ordinary afternoons when we could both relax, without schoolwork, job hunts, or simply, the stress of living a life.

Wonderful tale! Many thanks.

One quibble: "my parents’ generation was born into Maoist poverty”. Anyone born during Mao's 25 year administration was born into an unprecedentedly rapid rise in prosperity, literacy and longevity. In fact, China's takeoff under Mao was the fastest every recorded: at a steady 65% decadal growth, it was much faster than Germany, UK, US).

Though her description of her youth may sound like poverty to you, did she describe it that way, as 'poverty,' or say she was 'poor' growing up?