Ten new characteristics of changes in China's social class structure (Part 1)

China's social stratum structure is more complicated than in the early stage of reform on the socialist market economy

Good evening. Today feels a bit bittersweet. I said goodbye to my fitness coach of five years, who has decided to return to his hometown in north China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region to settle down and start a new chapter in life. When talking about him with friends, I often mention that he was more than just a fitness coach to me—he was, in some ways, like a therapist. He’s a man of few words, a great listener, and would sometimes share bits of his own life, which I came to rely on quite a bit. While I'll miss him, I completely understand his decision, and I genuinely wish him all the best for the future. His name is Xiao Longfei, and if you’re ever interested in learning about China’s fitness industry, I’d be happy to introduce you.

In recent years, a multitude of new economic and social organizations have emerged and grown rapidly. Particularly, new business forms represented by the platform economy have thrived, attracting a large number of new employment groups primarily engaged in flexible jobs, such as couriers, food delivery workers, rideshare drivers, and truck drivers. These groups are relatively mobile and flexible, making them the most active participants in economic and social development.

A 2023 survey on the national workforce revealed that 84 million people are now employed in new forms of work across China. In light of this, it’s unsurprising that a central conference on social work was recently held in Beijing from Nov. 5 to 6, and Xi Jinping's instruction was read out at the conference. In his message, Xi emphasized that social work is a crucial component of the Party and state's operations. He noted that "当前我国社会结构正在发生深刻变化 China's social structure is undergoing profound transformations."

Xi stresses high-quality development of social work -- Xinhua

当前我国社会结构正在发生深刻变化,尤其是新兴领域迅速发展,新经济组织、新社会组织大量涌现,新就业群体规模持续扩大,社会工作面临新形势新任务,必须展现新担当新作为。

Currently, China's social structure is undergoing profound transformations, notably with rapid advancements in emerging sectors. A large number of new economic and social entities are emerging, the demographic of groups in new forms of employment is expanding continuously, and as a result, social work is confronting fresh challenges and tasks, requiring relevant departments to shoulder new responsibilities and make new progress in this regard.

Cai Qi, a member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and a member of the Secretariat of the CPC Central Committee, attended the conference and delivered a speech. He stressed the necessity to reinforce Party building in emerging sectors as the top priority.

要把加强新兴领域党的建设作为重中之重,加强统筹协调,坚持分类指导,突出抓好新经济组织、新社会组织、新就业群体党建工作,推进党的组织覆盖和工作覆盖,促进新兴领域健康发展。

Cai stressed the necessity to reinforce Party building in emerging sectors as the top priority, strengthen coordination, and offer sector-specific guidance, with focused efforts on Party building among new economic organizations, new social organizations, and groups in new forms of employment, so as to expand the reach of Party's organization and the scope of its work, and promote the healthy development of emerging sectors.

The analysis of social stratum has long been one of the most pivotal issues in the research of Chinese society. As early as 1921, before the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Mao Zedong published his famous article 《中国社会各阶级的分析》Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society, in which he divided Chinese society into five main classes: 地主阶级和买办阶级 the landlord and comprador classes, 民族资产阶级 the national bourgeoisie, 小资产阶级 the petty bourgeoisie, 半无产阶级 the semi-proletariat, and 无产阶级 the proletariat.

Focusing on the propositions within the CPC at that time, Mao stated clearly in his article, "谁是我们的敌人?谁是我们的朋友?这个问题是革命的首要问题。Who are our enemies? Who are our friends? This is a question of the first importance for the revolution."

After the establishment of the People's Republic of China, Chinese scholars pursued various approaches to continue exploring this issue. A significant contribution was 《当代中国社会阶层研究报告》The Report on Contemporary Chinese Social Stratum Studies edited by 陆学艺 Lu Xueyi, a prominent sociologist and rural expert with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

The research team led by Lu Xueyi proposed a theoretical framework for understanding the stratification of contemporary Chinese society. This framework is based on occupational classifications and divides society according to the possession of organizational, economic, and cultural resources.

According to this framework, contemporary Chinese social structure is categorized into ten major strata: 国家与社会管理者 state and social managers, 经理人员 managerial staff, 私营企业主 private enterprise owners, 专业技术人员 professional and technical personnel, 办事人员 clerical staff, 个体工商户 individual business proprietors, 商业服务业员工 commercial service employees, 产业工人 industrial workers, 农业劳动者 agricultural laborers, and 城乡无业、失业、半失业者阶层 the unemployed or underemployed in both urban and rural areas.

In today’s newsletter, I’d like to share a fresh analysis of shifts in China’s social classes and their impact on governance. While the article leans toward an academic perspective, I found it highly relevant to the recent central conference on social work.

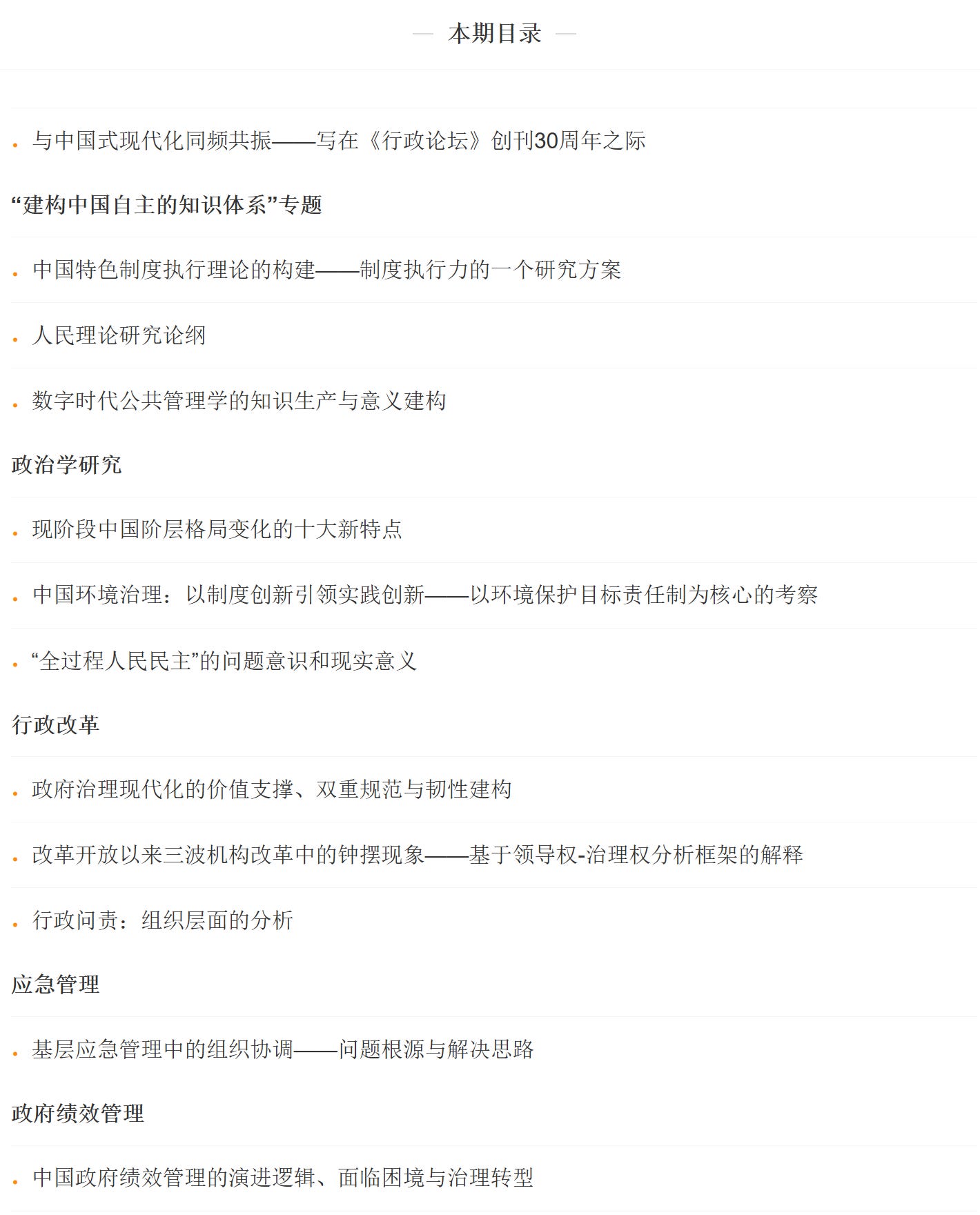

The piece was originally published in 行政论坛 Administrative Tribune, Issue 4, 2024, under the title "现阶段中国阶层格局变化的十大新特点 Ten New Characteristics Featuring Changes in China's Current Social Stratum Landscape." Administrative Tribune, first published in 1994 and formerly known as Management and Teaching, is a comprehensive academic journal overseen and published by 黑龙江省行政学院 Heilongjiang Academy of Governance (中共黑龙江省委党校 Party School of Heilongjiang Provincial Committee of CPC).

The article, co-authored by 朱光磊 Prof. Zhu Guanglei, director of the United Research Center of Chinese Government Development at Nankai University, and 韩林秀 Dr. Han Linxiu, research assistant with the same center, provides an in-depth analysis of the ten new characteristics of the social classes in contemporary China and offers a comprehensive view of the complex shifts in social mobility.

Given the depth and length of the article, we've split the translation into two parts for your reading convenience. In this edition, we cover the first five characteristics, with the remaining five to be featured in the next issue.

Highlights of today's piece:

1. Deeper integration of the blue and white collars in the expanding working class with their internal differentiation more pronounced

2. Further segmentation of traditional peasantry with the decline of agricultural laborers and the rise of professional farmers

3. Strengthened role of intellectuals in shaping the social cultural-ethical ethos in an era where higher education reaches more people

4. Growth slowdown of migrant workers due to policy adjustments and economic landscapes

5. Steep rise of individual laborers against the backdrop of rapid development of online platforms

Note: I’ll be posting the second half of the original article on GRR’s sister newsletter, Beijing Scroll. Occasionally, when I’m particularly busy, my friends or colleagues volunteer to help manage that account, which eases some of my workload.

The second half will look into new changes that have occurred to 私营企业主阶层 private entrepreneurs, 灵活就业者群体 flexible workers, and 公务员阶层 civil servants, as well as the consequent challenges brought up by these changes. Broader issues of widespread concern such as the macro status quo and general trend of the social stratum and mobility will also be covered.

[Introduction] In the past more than three decades, China has witnessed ultra-high-speed economic growth. Now, as that era draws to a close, the social development expectations that had formed are shifting, leading to increased anxieties, notably regarding "social stratification." So what is the actual situation about the demographic structure across different groups in China? How does it compare to the public's perceptions? This article, based on national statistics around 2023, encapsulates 10 characteristics of changes in China’s social stratum pattern, offering insights for individual perception and policy guidance.

The article highlights that the "working class," whether in a broad or narrow sense, has become the largest group in China. The number of traditional manual laborers is on the decline, while high-tech blue-collar workers and white-collar workers, who rely on communication and internet tools, are becoming more dominant. Workplaces call for professionals with stronger educational backgrounds and skills. The rural population continues to fall, with more traditional "farmers" replaced by a new type of agricultural workers. Meanwhile, the number of self-employed individuals, those in flexible employment, and private business owners is growing, calling for better public services in social security and career support. The migrant worker population has stabilized, yet there is still a way to go for their full "urbanization." The intellectual stratum comprises more professional skilled workers, different from the stratum of scholars and intellectuals in a traditional sense, still spearheading the development of social cultural-ethical ethos. Amid a greater demand for social and public services, the number of civil servants has seen modest growth, with a more optimized structure, as China cuts positions in central government departments and redistributes them to key areas, leveraging digital technologies.

The authors emphasize that education remains the most significant factor influencing social mobility in China. However, academic qualifications are increasingly becoming a necessary rather than sufficient condition for upward movement. Additionally, greater population mobility is driving changes in policies that are now unfavorable for such mobility. As for anxiety fueled by public opinion, the authors underscore that the insufficiency of resources per capita is a main cause of the current conflicts between different social strata, urging sound and stable policies to create an open and inclusive social environment that fosters cooperation and progress among all strata and groups.

Ten New Characteristics Featuring Changes in China's Current Social Stratum Landscape

The dynamics of China's social stratum structure represent the most fundamental and profound changes in its current society, shaping the direction of social development and public policy. Following massive social stratification and stratum reorganization in the late 20th century, social mobility has gradually stabilized and become more orderly. In this new phase, reform and opening-up continue to drive changes, while the new technological and industrial revolutions bring fresh momentum to stratification. Forces such as the private sector are also playing a unique role. On the whole, the movement of population in China is still full of vitality, as the shift in its social structure aligns with international developments.

As China ushers in a new stage of development, deeper internal reforms and broader external opening-up will inevitably bring a wider range of social groups into the new development wave. Under the combined influence of multiple factors, China's social stratum structure is more complicated than in the early stage of reform on the socialist market economy, exhibiting new characteristics.

The scale of the working class is expanding steadily. The number of white-collar workers increases continuously, and the integration between blue-collar and white-collar workers is improving, though internal differences are becoming more pronounced

In China, the term "working class" is traditionally used to analyze the political foundation of people’s power. As a basic concept reflecting the composition of social members, the working class covers a wide range of social members, including the working class in a narrow sense, civil servants, and professional skilled personnel; to some extent, military personnel and workers retiring from public service jobs can also be included in the working class.

At present, the working class in a narrow sense alone, that is, blue-collar and white-collar workers, has exceeded 400 million people. In fact, the working class, both in a broad and narrow sense, has become the largest, most influential, and widest-ranging group in China.

Here we focus on the working class in a narrow sense. The number of white-collar workers is rising, yet blue-collar workers still outnumber white-collar workers at a ratio of two to one. However, in the most developed metropolitan areas, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, the proportion of white-collar workers is higher. Overall, there is a trend towards integration between blue-collar and white-collar workers, albeit with some minor differences.

Such integration comes as the popularization of knowledge and widespread application of mechanization and electrification has led to a significant improvement in the qualities of blue-collar workers, considerably narrowing their gap with white-collar workers in terms of working conditions, salaries, and labor security, among others. Currently, the differences between blue-collar workers and white-collar workers are mainly reflected in salary level and access to public services between manual labor-focused blue-collar workers and creative-task-oriented white-collar workers.

The scope of blue-collar workers has expanded from physical workers, or traditional blue-collar workers, to include skilled workers. Physical workers finish their work with their physical power and simple tools. Manual labor often occurs in physically demanding, high-risk, and low-benefit links, including handling, loading/unloading, installation, and assembly mainly required in sectors such as engineering, construction, mining and metallurgy, garment manufacturing, and warehouse management and inventory control. These physical workers are mostly migrant workers with low levels of education. Now with the application of new technologies, including intelligent manufacturing and automation technologies, coupled with the popularization of vocational education and higher education, the number of these workers is shrinking while that of skilled workers is increasing.

Skilled workers, different from handicraft workers, craftsmen and artisans in history, undertake high-precision, high-efficiency, and high-level finish machining and product assembly mainly by operating machines proficiently. Their skills offer them greater access to stable jobs. In addition, they possess an obvious advantage over physical workers in working conditions and labor protection because they work in cleaner workshops thanks to the introduction of highly automated equipment such as digital and intelligent machines. Since the 1990s, the master-apprentice system has been gradually replaced by vocational and technical schools that have cultivated large numbers of high-quality skilled workers, and accordingly, skill level assessment standards have become more science-based and fairer. Skilled workers are essential for high-quality development of China’s industry system. According to data from The Ninth Survey of Chinese Workers, the number of workers engaging in skilled labor in China had surpassed 200 million by the end of 2021, accounting for more than 25 percent of the total employed population. Among them, workers without recognized skill level made up 74.5 percent of the total, while skilled workers recognized as senior workers and above represented only 5.4 percent. The gap reveals the fact that China lacks a sufficient team of skilled workers, especially high-quality workers.

White-collar workers consist of skilled white-collar workers and mental white-collar workers, both working in clean and suitable offices. The difference lies in their work pattern. Unlike mental white-collar workers undertaking creative tasks, skilled white-collar workers are usually not required to have independent thinking and their job even suppresses individual thinking. They just need carry out the tasks assigned by their manager or even do things per standard procedures, by finishing text or charts and communicating easy information via computers, the internet, and phones. By job nature, they are nothing different from skilled blue-collar workers operating machine buttons at factories, except that they rely on computers, the internet, and phones to work. For this reason, they earn about the same amount as skilled blue-collar workers, and even less than senior skilled blue-collar workers. Today fresh university graduates and most staff without a recognized rank belong to this social stratum. In an era where computers and the internet are prevalent, dedicated on-the-job training and years of education are no longer required of skilled white-collar workers, an underlying reason why highly educated employees are not satisfied with their work. And due to the fact that they can work anywhere, working overtime has become a defining feature of this group. The numerous similarities, from working conditions to salaries, are blurring the boundaries between skilled white-collar workers and skilled blue-collar workers, with more workers falling in between. This will contribute to "blue-white" integration and the emergence of middle-income groups. Compared with developed countries that have achieved modernization, China still lags behind in both the number of white-collar workers and skilled blue-collar workers and their share in the working population. There remains a certain level of social disconnect between blue-collar workers, especially manual workers, and white-collar workers. Their potential misperceptions of each other could hinder social cohesion and the high-quality development of China's industries.

Traditional peasantry is undergoing further segmentation, with the number of agricultural laborers continuing to decline. A new stratum of agricultural workers, dominated by professional farmers, is emerging.

In a broad sense, China's rural population consist of three overlapping layers: agricultural laborers, rural residents, and those with rural household registration (hukou). By 2022, these groups accounted for 177 million, 491 million, and 673 million people, respectively. The proportion of laborers engaging in the primary industry dropped dramatically from 70.5 percent in 1978 to 24.1 percent in 2022, yet still stands at a high level compared with European countries, the United States, Japan and other developed countries where the figure is below 10 percent. Restricted by the land area per capita and farming conditions, most arable lands are poorly mechanized. The shift towards large-scale and mechanized farming practices is serving as a catalyst for the further segmentation and evolution of the traditional farmer population. In the meantime, urbanization, which offers more jobs, higher salaries, and better living conditions, is pulling farmers towards a shift to urban workers. Between these push-and-pull dynamics, the number of traditional agricultural workers is shrinking by almost 10 million annually. Earlier social problems such as rural population "hollowing out" brought about by the movement of population will be gradually resolved through high-level development of population mobility. On the one hand, urban workers will move their families from the countryside to the city once they settle down. On the other hand, amid an increase in the rural population choosing to work or do business in urban areas and city development, some rural areas are becoming towns, offering affordable pathways for migration.

As the rural hukou population and rural residents continue to decline, the scale of agricultural laborers is stabilizing. At the same time, a new social stratum of agricultural laborers (the peasantry in a narrow sense) dominated by professional farmers is forming. New agricultural laborers turn agricultural labor into a profession, breaking away from the traditional "peasant" identity.

Unlike the past, these new agricultural laborers are not necessarily born in the countryside or into farming families. Urban residents moving to rural areas to engage in modern farming practices is already happening. In line with patterns seen in developed countries, these new agricultural laborers operate large portions of arable area per capita, promoting mechanization. Additionally, they possess technology, understand management principles, and are adept at business operations, fostering a stronger alignment with market demands. With the reform of the hukou system in place, rural living conditions, public services, and social security levels will improve. One thing worth noting, though, is that China's urbanization has slowed down and the number of farmers has fallen at a slower pace as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and a sluggish global economy. In 2022, agricultural laborers in China increased approximately 6 million compared to 2021, marking the first such rise in nearly 20 years. Currently, a new round of initiatives is being implemented to facilitate the urbanization of rural migrants. Supported by these policies, the number of agricultural workers and rural residents is expected to further shrink as population mobility reaches higher levels.

Intellectuals remain a pioneer in shaping the social cultural-ethical ethos and are playing an increasingly important role in guiding areas such as production, circulation, social governance, and public services.

In a broad sense, intellectuals include professional technical personnel (or intellectuals in a narrow sense), civil servants, and white-collar workers who have received university education and above and working in businesses. Broadly speaking, white-collar workers consist of those working in businesses (or white-collar workers in a narrow sense), professional technical personnel, and civil servants. The two groups overlap in source, educational background, and occupation, each having a core. In a working environment where theory and practice are fully combined, it is indeed very difficult to differentiate between them. Currently, the number of people who have received higher education (including junior college) is roughly equal to the number of intellectuals in a broad sense. According to data from the seventh national census conducted in 2020, 217 million people hold a junior college degree and above in China, accounting for 14.4 percent of the total population; this proportion was more than 20 times higher than the figure, or merely 0.7 percent, during the third national census in 1982. The huge increase demonstrated the development of China's education in more than four decades, during which illiteracy rate dropped to 2.67 percent and the retention rate of nine-year compulsory education reached 95.7 percent. This contrasted with the situation in the early stage of China's reform and opening-up, where most people were poorly educated. Higher education levels are pushing state life and public administration affairs to higher levels. Given the significant increase in the number of intellectuals in a broad sense, the term "intellectuals" alone would be no longer suitable as a benchmark concept for social stratum analysis. The concept of "intellectuals" in the ordinary sense of the word is in fact being marginalized, losing its ease of use.

In a narrower sense, intellectuals refer to social members engaged in the innovation and development of knowledge in philosophy and social science, natural science and technology, medicine and life, literature and art, and other fields relating to cultural progress. These intellectuals are committed to developing and creating new knowledge. They rely on platforms like schools, hospitals, and scientific research institutes to undertake cultural and professional technical tasks. They master scientific and cultural knowledge in a complete and systematic way, possessing outstanding depth in profession or technology. They are not what we called "literati" or "scholars" in the past. The term "professional technical personnel" might better describe this group. The Report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) emphasized that "Chinese modernization is the modernization of material and cultural-ethical advancement." Driven by science and technology, China has made remarkable progress in material advancement. At the same time, the whole society should emphasize cultural-ethical pursuit and social cultural-ethical ethos. This suits the needs of high-quality population development calling for higher levels of cultural-ethical trends, social administration and public services. Professional technical personnel can leverage their strengths to provide an abundance of superb cultural-ethical nourishment for social members and all sorts of organizations while educating the latter on correct scientific laws. In an era where higher education reaches more people, professional technical personnel play an active role in infiltrating the public into ideological and cultural building. These high-quality talents across various sectors indirectly influence the qualities of workers. For instance, a growing number of private-sector professionals now receive systematic training through higher education or professional degree programs, which exposes them to positive ideology, social cognition, and conduct, as well as a broader range of professional information both at home and abroad.

The migrant worker class is witnessing a slight slowdown in growth, in terms of both absolute numbers and the rate of growth, due to changes in the domestic and international economic landscapes, relevant policies, and other factors

Today the concept "township enterprise employees" has basically disappeared from academic research and policy making sectors. A generally accepted view is that migrant workers can be classified into local migrant workers (those who work in their own localities) and outgoing migrant workers (those who leave their hometowns and work in other places). The distribution of migrant workers is largely stable, with the latter category slightly outnumbering the former. Data from the migrant workers monitoring survey reports released by the National Bureau of Statistics over these years showed that China had 291 million migrant workers in 2019. Of them, 117 million were employed in their own province, while 174 million travelled outside their hometown for work. In 2020, following the outbreak of the pandemic, the total number of migrant workers in China decreased for the first time in history, standing at 286 million. By 2023, the figure reached a record high at 298 million, up 0.6 percent from 2022. That included 121 million local migrant workers and 177 million outgoing migrant workers. However, the rate of growth has declined. The number of migrant workers travelling outside their own province for work fell from 76.75 million in 2017 to 67.51 million in 2023. In the meanwhile, inter-provincial movement of working population has slowed down and even dropped, a trend worth attention. Alongside the temporary impact of the pandemic, government policies have played a big role in controlling the growth in migrant workers. On one hand, the negative impact of stubborn restrictions imposed by China's hukou system, such as unbalanced allocation of public services and resources, is becoming evident, and the cost of working outside is rising. On the other hand, provincial and local governments are introducing favorable employment policies to retain workforce within their regions with the aim of boosting development and urbanization.

Given the evolving economic and demographic landscape, the migrant labor population is unlikely to see significant growth in the future. For one thing, there is a smaller supply of migrant workers as the rural population is on the decline caused by two factors. First, population growth in China has turned negative and there is a declining population of childbearing age in "hollowed out" rural areas; second, the number of farmers across the three layers has shrunk in recent years. For another, policies are turning migrant workers into urban population at a pace that will surpass the growth rate of migrant workers. Nevertheless, the large population base in the countryside versus limited public resources in cities means that migrant workers will not fully get urbanized in a short period of time. Instead, the number of migrant workers will hit a growth plateau.

Migrant workers are increasingly becoming a transitional social class. First, 13.7 percent of the country's migrant workers are those with a junior college degree or above, many being fresh graduates who hold a rural hukou. They have more chances to secure stable jobs in cities, thus moving from the countryside to cities geographically and leaping from agriculture to industry and service sectors in employment form. Second, rural hukou holders are beginning to integrate well into urban life. At present, rural hukou holders outnumber rural permanent residents by 182 million. It is noteworthy that 128 million migrant workers lived in cities and towns by the end of 2023. In other words, these migrant workers have settled down in cities and towns. They are already an urban population in their employment and lifestyle, with their rural hukou being the last traces of their "rural identity." Third, since 2015, local migrant workers have contributed most to the increase in the number of China’s migrant workers. In fact, the real figure for local migrant workers might be greater than the statistics as the rural population often works part-time. Moreover, urbanization will turn more rural areas into cities and towns, and as a result, it would be inappropriate to still call rural residents farmers judging by their employment and lifestyle. By joining the workforce of migrant workers, rural agricultural laborers first become workers and then turn into "urban residents" in a different living environment, moving up the social stratum. We must refrain from employing the notion of "agricultural industrialization" as a veil to conceal the fact that a significant portion of the rural population has already shifted to the secondary and tertiary sectors.

The number of individual laborers has seen a dramatic increase in recent years, with the majority relying on online platforms for their employment

Individual laborers, among the first to develop and regain development vitality following China's reform and opening-up, have long played a "grassroots" role in the socio-economic landscape, meeting the employment and daily needs of urban and rural residents. Around 2000, the number of individual laborers slumped to 45.87 million due to factors such as the development of chain supermarkets and urban beautification campaigns. It is only in recent years that the number of individually owned businesses and relevant workers has increased again thanks to the rise of online shopping and improved management. Latest data from the State Administration for Market Regulation suggests that a total of 124 million individually owned businesses had been registered in China by the end of 2023, accounting for more than two-thirds (67.4 percent) of business entities nationwide. These businesses provided employment for nearly 300 million people in China. Such an enormous size points to the fact that the level of China's productive forces and its socialist market economy is still not high and relevant social systems and mechanisms still lag behind. Individually owned businesses, characterized by small capital requirements and diverse employment forms, have expanded job opportunities, particularly for low-skilled workers (such as women above 40 and men above 50), allowing them to increase household income through self-employment while reducing the government's public service and social welfare burden. These businesses serve as the foundation of the urban-rural employment structure, supporting livelihoods and promoting social interaction.

Individual laborers, first and foremost, are workers combining labor with means of production. Today's individually owned businesses are similar to those operating shops in the 20th century in that they still rely on family members as the foundation of cooperation. But there are also some differences. In the new development stage, individually owned businesses operate mainly through network services and mobile shopping. Unemployed population, housewives and migrant workers are the main force in the group, many being part-timers. Their income is moving to the ordinary level from a high in the late 20th century. Although web stores allow them to attract a broader range of customers and therefore earn more, most struggle to earn high incomes and are even low-income groups in cities. At present, the majority of newly-added individually owned businesses choose online shopping platforms and few operate physical stores. This trend stems from two main factors: the continuing impact of chain supermarkets and municipal regulations, and the low-cost, easily approved nature of online platforms, which eliminate concerns over storefront maintenance and utility expenses. Furthermore, backed by internet and communication technologies, individual workers today are connected with commodity manufacturers more closely. Individually owned businesses selling different sorts of daily necessities are similar to a salesperson of the manufacturer, but they no longer need to hoard goods and worry about their quality. Individual workers also have more flexible working hours since customers place an order via their online store before the manufacturer sends out goods directly. Of course, the rise of online platforms reflects to some extent the insufficient development of physical stores in people's neighborhoods and relevant services. In a world dominated by the internet, it is important to consider how to guide individual laborers in providing close and direct services to meet the urgent and personalized needs of neighborhood members. In particular, how to plan the layout of service-oriented businesses within cities and improve services are areas that warrant in-depth investigation by both the academic community and government departments. [End of first half]

It would help readers if you update this post by numbering the changes 1-10 and reduce the opening to a single paragraph.