The future of China's gig economy: Ride-hailing drivers and couriers at crossroads

The challenges faced by China's gig workers are side effects of socio-economic transformation, which also act as a driving force for the continuous improvement of the entire labor structure.

For years, the laid-off, unemployed, or those discontent with their income in China have always been reassured by the fact that they could dive into the mass of ride-hailing drivers and couriers and get reasonably paid.

Things have changed, however, as the internet business stagnates, and the job market saturates. The drivers and couriers are not earning as much as they used to, yet are unable to see any better offers.

People within the "new forms of employment" 新就业形态, e.g. ride-hailing drivers, food delivery workers and couriers, depend heavily on the expansion of the internet industry, and the majority of them are self-employed or outsourced. As a more flexible, and indeed more precarious, part of the job market, these workers are now grappling with the unfortunate consequences of their deep involvement in the fluctuating Chinese economy.

The following article is a sharp revelation of the cause of the predicament. It was originally published by 巨潮 WAVE, a WeChat account focusing on Chinese businesses. The author predicts an impending third wave of labor migration. Decline in population growth and consumption are the primary factors behind income stagnation, the author explains, and the solution can only come from the workers themselves, by upgrading skills and entering new fields.

There was a time when migrant workers had the guts to proclaim: "It's no big deal. I'll just quit and be a DiDi (the Chinese equivalent of Uber) driver!"

And this was no tongue-in-cheek remark. The rise of China's online taxi market has contributed significantly to the country's employment rates. DiDi's financial report shows that from March 2020 to March 2021, the company had 13 million annual active drivers in China; from March 2022 to March 2023, the number rose to 19 million, an increase of nearly 50 percent in just two years.

According to data from China's Ministry of Transport, as of April 30 2023, a total of 309 ride-hailing companies had obtained operating licenses, and a total of 5.41 million ride-hailing driver licenses had been issued across the country.

In contrast, those two figures stood at merely 207 and 2.55 million, respectively, on Oct. 31 2022. That counts as an increase of 49.2 percent and 112.4 percent, respectively, in less than three years. But the surge in ride-hailing drivers is by no means good news for those who want to join the industry. Data show that the average daily number of orders received by ride-hailing drivers has now decreased from 23.3 orders per car in 2020 to less than 11 orders per car.

This means that while the overall market has barely expanded. It now has to cope with an ever-larger number of people who seek shelter in the industry, resulting in a huge drop in the average income of drivers.

In fact, it's not just ride-hailing drivers that are experiencing such embarrassment. The same thing is happening to the other two professions among the top three retreats for migrant workers: couriers and food delivery workers. They are now faced with the cruel reality of increased staffing and stagnant income growth.

What can migrant workers resort to now that there's hardly any space for a retreat?

01

The march of migrant workers

It seems that the "bottomless pit of employment" can indeed be filled up.

The term "dagong" (打工 in Chinese, referring to casual labor in the city) first appeared in Hong Kong. But the full rise of the term in China is attributed to two historical migrations of the Chinese labor force.

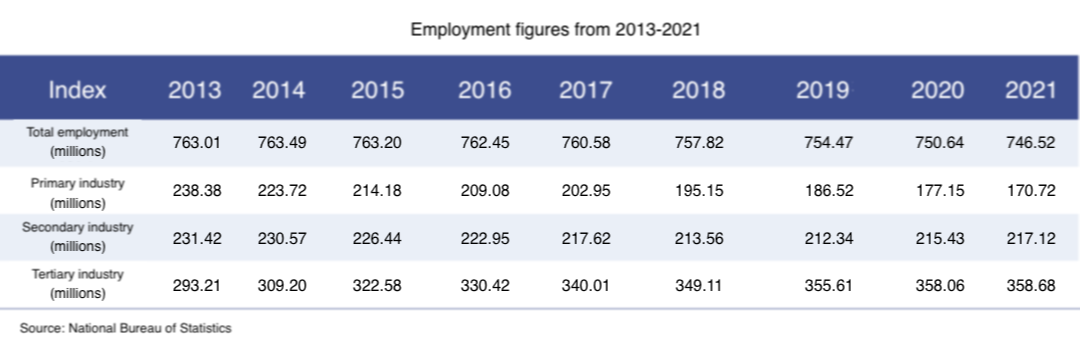

The first labor migration took place in 1991. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, the number of people employed in China's primary sector fell for the first time in 1991 since the reform and opening up, and continued to fall for more than thirty years thereafter. This marked the continued migration of agricultural labor.

China's manufacturing and construction industries grew rapidly during this period and became the main force behind employment. Large numbers of agricultural laborers turned into industrial and construction workers, and their low costs helped China gain a reputation as the "world's factory".

But dangers lie under the facade. For a start, low wages, though an advantage of China's manufacturing industries, also has a detrimental effect in terms of continuing to attract labor. Second, long hours of tedious work at the assembly lines were inhuman and depressing, the effect of which was felt most keenly in the "thirteen consecutive suicide jumps" at Foxconn.

Low-end manufacturing jobs may be acceptable for the older generation, but for people born in the 1980s and 90s, they are far from attractive.

So it came to pass that a second migration of the workforce took place.

The turning point was 2013, when the number of people employed in China's secondary sector saw a historic decline. In the following two years, the total number of people employed in China and the number of people employed in primary and secondary industries all fell, while only the tertiary sector bucked the trend and became the most dynamic part of the job market.

In 2013, DiDi and Kuaidi, two major ride-hailing companies at the time, officially opened for private car operations and launched a rain of subsidies. Uber, DiDa, Shenzhou (Ucar), and other rival companies all followed the practice, using subsidies to gain market dominance. The lure of subsidies attracted many private car owners into the game and brought into existence a formidable group of full-time ride-hailing drivers.

In 2013, Meituan triumphed the dogfight to start its takeaway services, marking the emergence of food delivery workers.

In 2013, supported by the booming e-commerce business, the annual business volume of major courier service providers exceeded 9.19 billion pieces, an increase of 61.6 percent year-on-year -- the highest growth rate on record. The year 2013 thus marked the beginning of the golden age of China's courier industry.

The Ninth National Workforce Survey released on March 26 2023 showed that the total number of employed workers in China is currently around 402 million, with 84 million classified as being in "new forms of employment." People in the "new forms of employment" mainly include truck drivers, ride-hailing drivers, couriers and food delivery workers.

These people have taken up over 20 percent of the population, which demonstrates how the new forms of employment, as a result of the Internet, are functioning like a reservoir that constantly absorbs water from other fields of the job market.

The reservoir is so huge that not until 2022 did we realize that it's not a bottomless pit. Now it is on the edge of brimming.

02

A Brimming Reservoir

The scale of the Internet economy has peaked.

Theoretically speaking, the internet platform economy is limitless to accommodate a massive workforce.

However, it is evident that the economic pool constructed by China's internet has hit its limit since 2022, mainly due to the plateauing of the population and the number of netizens:

China's population has reached its peak. By the end of 2022, the national population decreased by 850,000 compared to the previous year, a negative growth for the first time in decades. Additionally, there is little possibility of a short-term population rebound.

The number of Internet users has stretched to its limit. According to the 51st Statistical Report on Internet Development in China, published by the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) in March 2023, as of December 2022, the number of netizens in China reached 1.067 billion, with an internet penetration rate of 75.6 percent.

Considering that the population aged 15-64 accounts for 81.8 percent of the total population in China, there is practically no room for the growth of Internet users.

Furthermore, the decline in purchasing power also has impacts on the scale of the Internet economy. In 2022, the national per capita consumption expenditure was 24,538 yuan (about 3,444 U.S. dollars), a nominal increase of 1.8 percent compared to the previous year, but after deducting price factors, it actually decreased by 0.2 percent. Among them, urban residents, who are the main force of consumption, had an average per capita consumption expenditure of 30,391 yuan, a nominal increase of 0.3 percent, but a real decrease of 1.7 percent after deducting price factors.

The number of consumers has reached its peak, and consumption capacity is declining. These two factors that affect market growth are forcing a slowdown in employment related to the internet economy.

A speck of dust from the era eventually weighs as a mountain on the shoulder of each ordinary individual.

According to a report by China Newsweek, as of May 16, 2023, Changsha City, capital of central China's Hunan Province, has suspended the issuance of new permits for ride-hailing. Prior to this, multiple cities including Dongguan, Sanya, Wenzhou, Jinan, and Suining had successively issued warnings of saturation in the ride-hailing market. Even in first-tier cities like Guangzhou, capital of south China's Guangdong Province, the average daily orders and revenue have been decreasing month by month from January to March this year.

Several food delivery riders in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, in an interview by Red Star News, all revealed that after the Chinese New Year, there were "more riders but fewer orders." These full-time food delivery workers now typically receive only 20 to 30 orders per day, compared to their previous peak of receiving 50 to 60 orders.

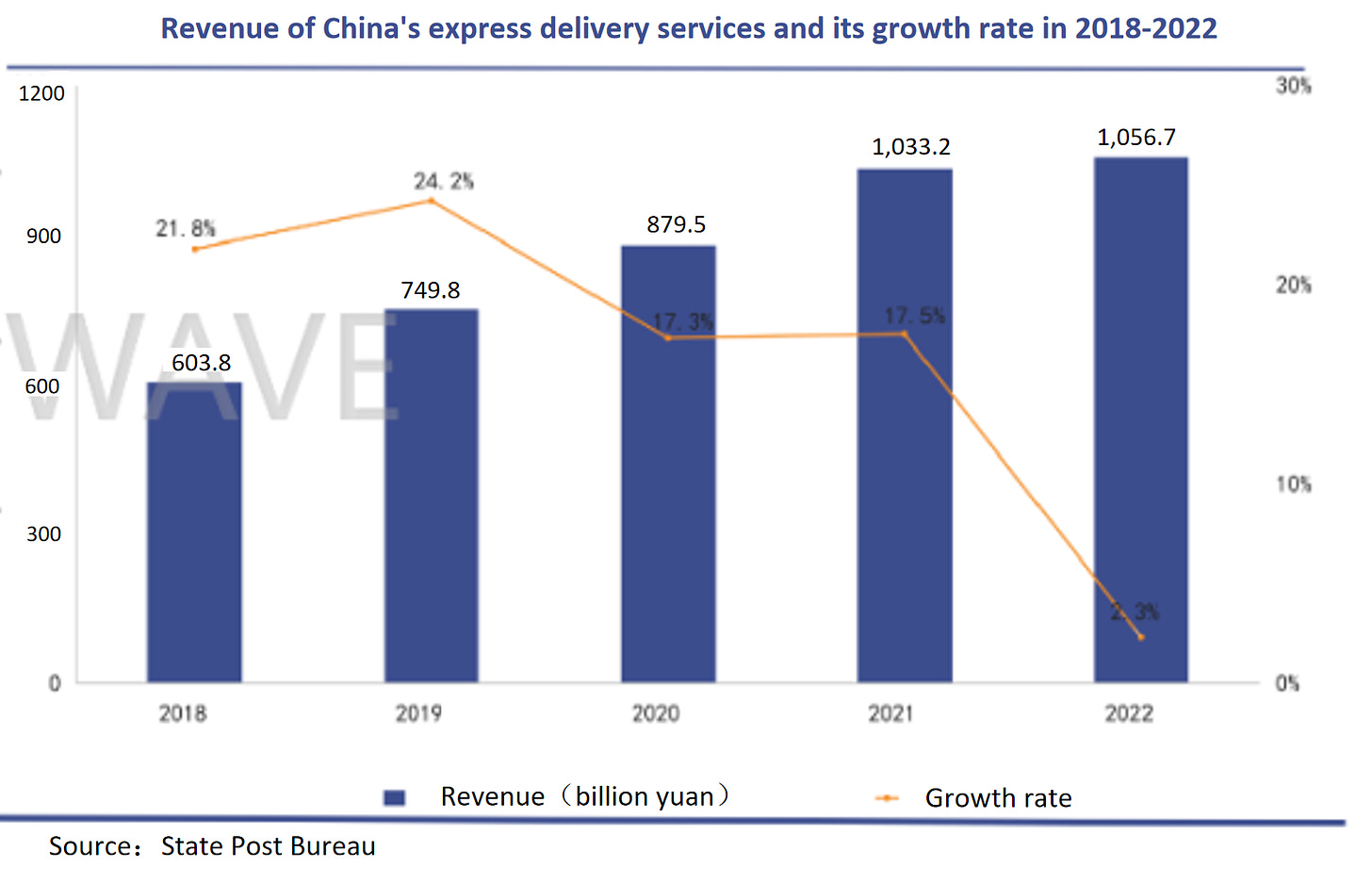

Life is also tough for couriers whose work is highly dependent on e-commerce consumption. In 2022, the volume and revenue of China's express delivery services experienced the lowest growth rate recorded, both below 3 percent. As a result, the per capita usage and expenditure on express delivery services in 2022 remained stagnant.

For many migrant workers, the so-called "employment shelter" has actually disappeared, making it unaffordable for them to lose their current jobs.

03

Is it time for the third labor migration?

Actually, the key to all kinds of labor migration is skill upgrading.

The first two waves of labor migration in China have already passed, and a third wave may be on the horizon. The author identifies three potential directions for this migration.

First, go back to rural areas.

It is worth noting that in 2022, after experiencing years of decline, the number of people employed in China's primary industry saw an increase for the first time.

This may be attributed to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2022. However, the significant outflow of rural population has led to serious hollowing out of rural areas, posing significant challenges to China's agriculture such as population aging and a shrinking farming population. To address these issues, it is essential to accelerate the process of agricultural mechanization, intensification, and intelligent production, which requires an influx of fresh and young labor to enhance agricultural productivity and stabilize output.

Technical agricultural positions will create a substantial number of employment opportunities.

Second, become skilled workers.

A significant number of laborers are leaving factories in China, driving rapid industrialization, mechanization, and automation in China's manufacturing sector. In many factories, the repetitive tasks on assembly lines can now be replaced by robots and mechanical arms. However, skilled workers cannot be immediately replaced by automation, creating a significant skill gap.

In the industrial sector, the ideal talent structure is 1 scientist, 10 engineers, and 100 skilled workers. In Japan, highly skilled technicians account for around 40 percent of the entire industrial workforce, while in Germany, the figure reaches as high as 50 percent. In China, this proportion is only about 5 percent.

Third, upgrade the service.

Throughout the development of some industries such as online ride-hailing, food delivery, and express delivery, rapid scaling has been achieved through aggressive price competition, subsidies, and even dumping. After extensive and market-share-focused strategies, the upgrade of service quality becomes necessary. This entails meeting a series of more specialized and specific market demands.

In a word, the reason why migrant workers flock to industries such as express delivery, food delivery, and online ride-hailing is simply that these jobs have low entry barriers and that they can quickly start working and earn a decent income. However, these low-skilled positions may enjoy the benefits in the early stages of industry development but will eventually be assigned market value that aligns with their skills level due to the rapid increase in labor supply.

The migrant workers also conform to the laws of supply and demand.

To maintain the "job freedom" of migrant workers, there is only one core direction in all sectors: skill upgrading.

Just as the first wave of labor migration was based on the universalization of compulsory education and the improvement of cultural literacy, the second wave of labor migration was driven by the popularization of Internet technology skills.

Overall, the challenges faced by various tertiary industry positions, represented by online ride-hailing, are actually side effects of socio-economic transformation. At the same time, they also act as a driving force for the continuous improvement of the entire labor structure.

However, not everyone can progress with the times.