Vietnam or India: which one will be the new "world's factory"?

"China's current business ties with Vietnam are more cooperative in nature, while those with India come with more competitive features."

The following article, published on May 22, was from 财经十一人 Caijing Eleven, a column created by eleven professional financial journalists from the industry reporting team of 财经 Caijing magazine. (Author: Liu Shuqi, Chen Yinfan and Gu Lingyu. Editor: Xie Lirong).

On May 10, U.S. President Joe Biden said Washington might drop some of the tariffs imposed against Chinese imports. According to the article, as the news spread, some Chinese business owners found that their clients' requirements for orders outside China were less severe than before. As the stories in the article indicate, the United States' tariffs had a substantial impact on supply chains, particularly the relocation of factories of companies doing business with the United States in recent years. The present phase of industrial migration, however, has begun ten years ago, with a variety of causes for the industries' "exodus."

The article points out that despite the fact that both Vietnam and India are major destinations for China's migrating electronics industry, Vietnam seems to China as a collaborator, whereas India comes off as a competitor.

The article also mentions that the business climate in the south and southeast Asian countries has its own set of issues. Industrial chain spillover is not necessarily a bad thing for Chinese enterprises that take the initiative to "go global," and China's dominant position will not be challenged in the short term.

In a previous GRR piece, China's plans to complete its industrial transformation, as well as its efforts to become less reliant on other countries in several key industries and technologies, were discussed. Through these articles, GRR hopes to provide you with a broad and comprehensive view of the opportunities and challenges China faces as "the world undergoes changes unseen in a century."

The translation, which was done by GRR, hasn’t been reviewed by the author. Errors may well exit. The content here is neither official nor authoritative, as this is just a personal newsletter.

***

The assembly line in an electric car factory located in Haiphong, Vietnam (Source: AFP)

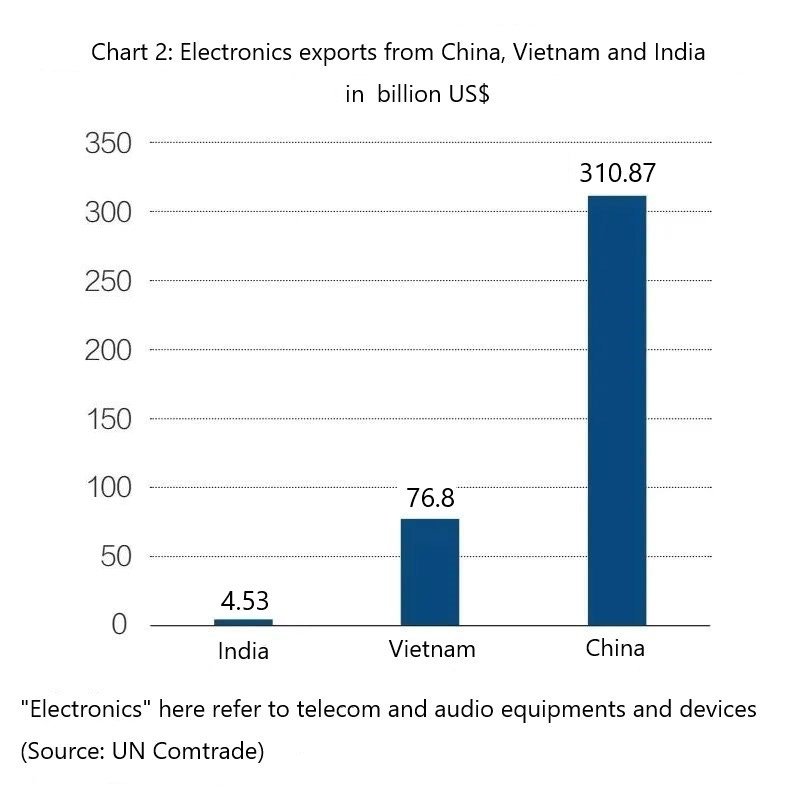

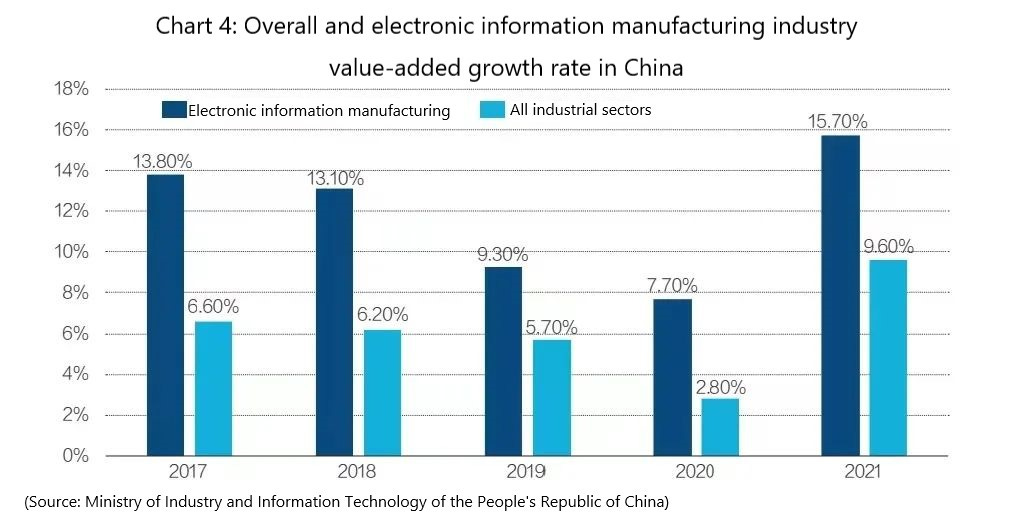

China's sci-tech manufacturing industry boomed over the past two decades. In Henan Province, Zhengzhou became home to some 300,000 workers in their prime, who churn out about half of the Apple smartphones in the world in the 5.6-million-square-meter Foxconn plant. Over 800 new A-share listed firms have emerged from the thriving electronics, computer, and telecommunication industries. Over the last ten years, the value-added of China's electronic information and manufacturing industries has grown at an average rate of 11 percent, which is consistently greater than that of the country's overall value-added of industries.

The city of Shenzhen in south China's Guangzhou Province is the heart of China's sci-tech manufacturing industry. It is home of leading Chinese tech firms including Huawei, ZTE, DJI and BYD. In 2021, the city's the value-added of manufacturing accounted for over 30 percent of the city's gross product, and over 70 percent of these value-added are created by hi-tech manufacturers.

For those who are looking for a job at Shenzhen's electronics factories, the swarming talent market near a bus depot in Longhua District is usually their first stop. With their unopened luggage in hand, they'd proceed to the line of stalls set up by employment agencies, and then get dispatched to one of the countless electronic workshops in the city.

Similar episodes are being played out today in countries like India and Vietnam. According to statistics from the CMA, an association of India- and Vietnam-based Chinese mobile phone companies, about 200 electronics enterprises - most of them from the Chinese mainland, Taiwan and Hong Kong - have set up plants in India, with another 150 doing so in Vietnam. These numbers only included supply chain enterprises with considerable market sway. Aside from these big names, many small and micro-sized supporting enterprises also set up shop there.

Take the mobile phone industry - a subsidiary industry that involves the most profound and most systemic division of labor in the global scale - as an example. China used to be the world's factory for mobile phones, but things are now changing. Figures from third-party research institution Counterpoint showed that, China accounted for 67.4 percent of the global mobile phone production in 2021, down from 75 percent in 2016. Meanwhile, mobile phone production in India and Vietnam has been gradually picking up speed.

There is a complex set of causes behind the migration of the electronics industry, which can be broadly categorized into the following:

1. Natural industrial transformation and upgrading - sectors with lower value-added are channeled to countries with cheaper labor and land.

2. Tariff policy changes of various countries - enterprises relocate their production for economic efficiency considerations, driving upstream segments of the industrial chain to shift.

3. Impacts of external environment such as international politics and the COVID-19 pandemic - foreign companies are facing greater challenges in China, prompting some to exit the country.

It is worth noting that a number of experts studying industry chain migration in India and Southeast Asia have said that the electronics industrial chain isn't leaving China for good. Rather, it is formulating a multi-location global layout, which can serve as an attempt for both market development and risk diversification. Foreign companies are shifting from the past strategy of "All in China" to "China + N,” but China's competitive advantages will not diminish in the short term.

“We might as well call it ‘expansion' instead of ‘relocation',” said the head of a Chinese-funded enterprise who has worked in India for more than a decade, “It's like a couple having a second child -- their first ‘baby' is still there.”

Moreover, industry that remained in China is gradually upgrading. Chinese customs data on the cell phone industry might help shed some light in this regard - China's exports of cell phones fell 1.2% year-on-year to 950 million units in 2021, but the value for those exports grew 9.3% to 944.7 billion yuan. Similar patterns in the figures have been observed over the last five years.

“The outbound relocation of the industrial chain is a neutral terminology,” said Xu Qiyuan, deputy director of the Institute of World Economics and Politics under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. According to Xu, excessive outbound industrial relocation will hollow out China's industry, whereas relocation within a reasonable range is but a natural process of industrial upgrading. It can be conducive to the formation of an international labor division network with China as a key link, and to the elevation of the international influence of China's own industrial chain.

This does not, however, mean that China's sci-tech manufacturing chain can rest on its laurels. In the midst of a new round of industrial revolution and geopolitical frictions, it requires great wisdom to secure the existing advantageous position of China's sci-tech manufacturing industry, form a close transition between old and new production capacity, to seek cooperation and achieve leapfrog transitions.

01 The many reasons behind the factories' “exodus”

Xie Hong, head of the Guangdong Council for the Development Promotion of Small and Medium Enterprises, has visited tens of thousands of small and medium-sized businesses with his team in the past 17 years. He is well aware of the slightest changes in the shifting landscape of the global supply chain.

The current round of industrial relocation began ten years ago. With the cost of practically everything growing in China, factories had to look for cheaper alternatives elsewhere. On the one hand, the cost for labor in China was rocketing: the wages in China's Pearl River Delta region was as high as 5,000 (about 750 U.S. dollars) to 7,000 yuan a month, compared to 700 to 1,000 yuan in many Southeast Asian countries. A 5,000-yuan cost reduction in each worker can translate into an extra 5 million yuan in profit per month for a factory with 1,000 employees.

On the other hand, factory building subletting was in its heyday in the Pearl River Delta region. For many factories, rising rental costs are making their businesses unsustainable. A business owner of a hardware factory in Southeast Asia said that, back 2012, his friends' electronics and footwear factories in Dongguan, Guangdong Province could generate less than one million yuan in profit every year. However, the rent for a plant similar to their could amount to as high as 3 million. In the end, more and more factory owners chose to sublet their plants, and this in turn drove rental prices for factories even higher.

In the meantime, many Southeast Asian countries have opened up wider to the world to attract businesses. According to a 2021 Ernst & Young brochure titled “Doing Business in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)”, investors in Vietnam can enjoy a preferential tax rate ranging from 10 percent to 17 percent for several years or the entire investment period. In addition, they are also entitled to a tax exemption period of up to four years and a 50-percent tax reduction period of up to nine years.

As a result of rising domestic pressure at home and favorable conditions abroad, sci-tech manufacturing businesses in the Pearl River Delta have been slowly migrating out of China over the past decade. Now this process is being accelerated by changes in the international trade environment in recent years.

Trade tensions between China and the United States is one of the core reasons for the acceleration. Since 2018, intensifying trade frictions between China and the United States (U.S.) has led the U.S. to impose multiple rounds of tariffs on Chinese products including electronic parts which took up a large bulk of the tariffs. Thus far, the total worth of the products involved has surpassed 500 billion U.S. dollars.

According to Xie Hong, while previous rounds of industrial relocation involved mainly labor-intensive businesses (garment, furniture), the latest round featured more technology manufacturers.

Pressure is being transmitted from the bottom up in the supply chain. An industrial park in northern Vietnam, which had been left vacant ten years after its establishment, was suddenly crammed with enterprises and workers months after the China-U.S. trade tensions broke out. Most of the enterprises that moved in were electronics firms included in the U.S. sanction list, and related upstream and downstream companies.

Their U.S.-based clients were very straightforward with what they want. “They would approach three suppliers, and tell them whoever willing to relocate to Southeast Asia would get the contract,” Xie said.

Wu Geming, board member of Hanyu Group, had a memorable experience in this regard. Three years ago, the group was asked to relocate a section of its supply chain abroad during a teleconference with its U.S. clients. If it refused to do so, the clients would have considered choosing a new supplier. Hanyu, which focuses on the development, production and sales of drainage pumps for energy-efficient household appliances, is a leader in the industry. Its customers include electronics heavyweights such as Whirlpool, General Electric and Samsung. Unfortunately, as per a list by the Trump administration, additional tariffs were imposed on its products.

Wu’s list for candidate relocation sites boiled down to three countries: Vietnam, India, and Thailand. India is too far away; Vietnam, despite sharing similar traditions with China, is prone to be affected by uncontrollable factors. In the end, Wu and his colleagues chose to relocate their injection molding workshops and part of the assembly lines to Pin Thong Industrial Estate in Chonburi, Thailand. Located between Bangkok and Pattaya, the area was already home to a number of Japanese and South Korean enterprises, so the supply chain is comparatively mature. Soon afterwards, Hanyu built its new factory building near the Thai port of Laem Chabang.

The manufacturing of drainage pumps consist of two parts: motor production and final assembly. For the time being, production lines for the motors - which touches on Hanyu’s core competitiveness - are staying in China, for Thailand’s supply chains and local technologies were still insufficient to sustain it. Thailand does not have steel plants that could provide corresponding parts, nor could it provide raw materials need for the pump production such as aluminium wires, copper wires and rare earth.

Wu is not alone. Zhong Qing, owner of a Pearl-River-Delta-based manufacturer of Christmas electronic crafts said his firm was also hit hard by the trade frictions. The United States is one of his company's major markets, but high tariffs have hiked export costs, said Zhong. His U.S. clients made it clear - only 7 million U.S. dollars worth of products in the 10-million-dollar contract can be exported from China. The rest had to be exported from elsewhere.

Sometimes, the U.S. clients would even ask the manufacturers’ supporting companies to join the relocation out of China. Xie Hong has noticed that a number of factory building construction companies and steel structure firms were also on the list of relocating enterprises. He projected that at this rate, Southeast Asia will be able to form a well-developed electronics industry chain within three to five years.

Xu Ning is the CEO of Bonsen Electronics Ltd. The Guangdong-based enterprise has long been engaged in the production and global marketing of office equipment and kitchen appliances, with the United States being its largest market. To offset the impact of U.S. tariffs and cater to its production capacity expansion, Xu had a new production base established in Vietnam’s Hai Duong province, where the company produces paper shredders, binding machines and other office equipment for the U.S. market.

The Hai Duong province saw it opportunities coming ten years ago when the Japanese government asked its domestic firms to relocate their production to Southeast Asia as a result of political frictions with China. Today, Hai Duong has emerged as the global center of printer and copier production.

Indeed, Vietnam is perhaps the biggest winner of the China-U.S. trade war. Since 2019, the total value of the country's export has consistently surpassed that of Shenzhen, thanks to increase exports to the U.S., Vietnam's largest overseas market. In 2021, Vietnamese exports to the U.S grew 25 percent to 96.3 billion U.S. dollars. In particular, the export value of computers, electronic devices and their parts exceeded 10 billion U.S. dollars, ranking the third in all export categories.

If the tariffs imposed by the U.S. is forcing some electronics manufacturers out of China, India's tariff policies are in many ways serving to keep them inside the South Asian subcontinent.

In 2014, the Modi administration proposed the “Made in India” initiative, with the goal of elevating the proportion of manufacturing in India's GDP from 15 percent to 25 percent, so as to reduce the country's manufacturing industry's disadvantages. One of the government's strategies is to raise tariffs on mobile phones and parts, to force manufacturers to build factories in India.

Since 2017, India’s mobile phone import tariffs have seen steady gradient increases, starting from 10 percent. According to Yang Shucheng, secretary general of CMA, the country’s current tariff on mobile phone import stands at over 25 percent, while the supply chain tariff is about 15 percent. Only a small number of components or accessories are exempt from tariffs.

(the data above is for the year of 2020)

The aforementioned Chinese business owner in India had witnessed the entire process of Chinese mobile phone industry’s relocation to India. He recalled that Chinese companies’ willingness to migrate to India was not strong at first. But after India’s domestic mobile phone manufacturer Micromax began constructing its own assembly lines around 2014, the country raised the import tariffs on assembled mobile phones. Under such circumstances, other manufacturers were forced to follow suit, lest risk losing their advantage in price.

So far, OPPO has invested 24 billion Indian Rupees on its Indian plants. Vivo, meanwhile, has invested 19 billion and said the number would be increased to 35 billion by 2023. Xiaomi does not have its own plant in India, but it has already set up seven smartphone factories in association with Foxconn and Flextronics International.

In addition, India's smart phone market is dominated by low-end smartphones with price tags of around 1,000 yuan. That translates into extremely thin profit margins. In order to reduce production costs, some mobile phone manufacturers would require supply chain enterprises to set up factories in India. “If they don't, they'd having trouble getting domestic contracts, ” Yang said.

Now, in India’s Uttar Pradesh, a city named Noida is bearing the country's hope of revitalization through strong manufacturing. Only a half hour's drive from New Delhi, the city is densely populated with electronics factories from China. Apart from mobile phone makers like OPPO, Vivo and Transsion, the city also attracted other companies such as battery maker Sunwoda, parts manufacturer Everwin Precision, mobile phone camera maker Q Tech, fingerprint recognition company Holitech and packaging manufacturer Liujia.

If it weren't for the Indian youngsters who roam the streets, one would easily mistake the city for Shenzhen's Longhua district.

02 Vietnam for cooperation, and India for competition

Vietnam and India are the two main destinations of China's relocating electronics industry. But their respective tariff policies and geographical locations have led the two took onto different paths in the development of electronic manufacturing. Vietnam took the road to become the “world’s factory,” while India seeks to emerge as a major power in manufacturing. Neither of these two paths would lead to a simple replacement of China's role.

Limited by its weak domestic demand, Vietnam’s role in the global electronics industry chain is more of a processing and transshipment hub, producing goods that in then end would travel across the ocean to North America, Europe, and other destinations. As for India, the reasons why it could attract a relatively complete electronic industry chain are two-fold: In addition to its tariff adjustment, India also has a vast domestic market, so most of the electronic products produced in India are sold locally rather than exported.

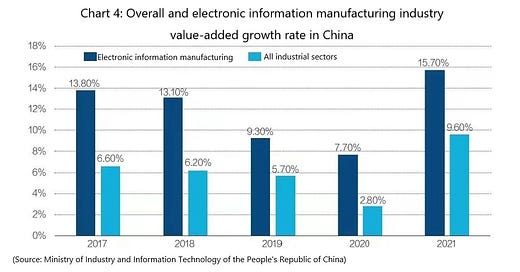

Data from the UN Comtrade showed that in 2020, the total export value of electronics-related industries in India was 4.53 billion U.S. dollars. Vietnam's export, however, amounted to 76.8 billion U.S. dollars, nearly 17 times that of India. The export value of China's electronics industry that same year was 310.87 billion U.S. dollars, four times that of Vietnam and 68 times that of India.

But Vietnam is way behind India in terms of the completeness of its industrial chain.

Vietnam's electronics industry mainly revolves around a limited number of industrial heavyweights, namely Samsung, Foxconn, Canon and LG, with Samsung making the biggest investment in Vietnam. After Samsung's mobile phone lost the Chinese market, Samsung shut down its last China-based factory in Huizhou, Guangdong Province in 2019, and relocated its entire production capacity to Vietnam, India and Indonesia, which led about 200 supply chain manufacturers to migrate to Southeast Asia alongside. At one point, 60 percent of Vietnam's supply chain manufacturers only did business with Samsung and LG.

By the end of last year, Samsung's total investment in Vietnam reached 17.74 billion U.S. dollars. This February, Samsung Electro-Mechanics, a subsidiary of Samsung, announced that it would invest another 850 million U.S. dollars in Vietnam to build a production line for FC-BGA packaging substrates. FC-BGA packaging substrate is a type of high-end semiconductor packaging substrate, which is mainly used for packaging large computing chips such as CPUs and GPUs. This means that Samsung is bringing more advanced processes and technologies into Vietnam.

As quipped by some, “Samsung is hold up Vietnam's electronics industry single-handedly.” The statement is somewhat exaggerated, but not without merit.

In India, however, lower labor costs and higher tariffs have brought together only supply chains of Samsung and Apple, as well as those of OPPO, Vivo, Xiaomi, Lenovo, TCL, Haier, Midea and other electronics and home appliance industry firms, to take root in India and expand operations here. "With the exception of cover glass and mold, all links in the mobile phone supply chain are now present in India," Yang said. He noted that India has yet to meet the requirements for the relocation of cover glass and mold factories, which needs higher water quality and steady power supply.

Samsung has already shifted some low-end mobile phone production lines to India, where labor costs are lower, in recent years. According to media report by South Korea’s The Elec, Samsung will reorganize its global smartphone production plan in 2022, and expand the production capacity of its Indian factories from 60 million units per year to 93 million units per year. Currently, Vietnam and India respectively account for 60 percent and 20 percent of Samsung's global production capacity. After that reorganization, the distribution will become 50 percent and 29 percent.

Apple has a different story. The number of plants set up by Apple's top 200 global suppliers in Vietnam has increased rapidly from 14 in 2018 to 23 this year, while those in India is much smaller and growing at a slower pace, having increased from seven in 2018 to nine this year.

And yet between Vietnam and India, it was the latter that took over Apple's more essential production lines. Ivan Lam, a veteran analyst with Counterpoint, said that while Apple’s production lines in Vietnam focused on the manufacturing of AirPods and a small number of iPads, India is already making older models of iPhones. And although the bulk of Apple’s latest iPhone models are still produced in the Foxconn plant in Zhengzhou, all signs indicate that India is increasingly capable of taking up the production of newer iPhone models.

The rapid development of India's manufacturing is not to be underestimated. In the past, India mainly produced older iPhone models like SE and 6S. But since 2020, Apple has shifted the production capacity of newer models - including iPhone 11, 12 and 13 - to India. According to Lam, India’s iPhone production will take up 5 percent of Apple's total production in 2022.

As of 2021, over 90 percent of Apple products are produced in China. India contributed for 3 percent and Vietnam took up less than 1 percent.

Already, India is no longer content with absorbing its increasing production capacity at home. It wants to become a global manufacturing hub. In a 2019 National Policy on Electronics (NPE), the country set a goal to produce 1 billion units of mobile phone by 2025, of which 600 million units would be exported to other countries. These phones are projected to create a total turnover of 130 billion Indian rupees, accounting for half of the total turnover of India’s electronics industry.

In the past, OPPO and Vivo mainly produced products priced between 800 yuan and 1,600 yuan in India, as a result of the low consumption capacity of the Indian market. These two Chinese firms’ middle and high-end products were all made in China. But now things are starting to change. Vivo India’s Director-Business Strategy Paigam Danish said in an interview that Vivo will produce its flagship X80 series mobile phones in India this year, and will increase its annual production capacity of mobile phones in India from 50 million units to 60 million units before the end of the year. The extra production capacity will mainly be focused on export.

“For China, Vietnam comes off as collaborator, whereas India comes off as a competitor,” a number of interviewees have expressed similar views.

Xu Qiyuan noted that between Vietnam and China, both competition and complementarity exist. But from in terms of competition, the pressure the two countries experience with each other is completely asymmetric, with China occupying an absolute advantage on its side. In terms of complementarity, since the export structure of the two countries is quite different, and their supply chains closely depend on each other. For example, when China was hit by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, many industries' supply chains in Vietnam came to a halt.

"In fact, China's direct investment in and industrial relocation to Vietnam has brought the two countries closer in terms of the international division of labor," Xu said. A portion of China's trade surplus with Europe and the U.S. was converted into China's surplus with Vietnam and Vietnam's surplus with Europe and the U.S., and China's pressure from excessive concentration of international unbalance of payments has been relieved.

According to Li Wei, a professor with the School of International Studies of Renmin University of China and director of the university’s Economic Diplomacy Research Program, Vietnam's development is the outgrowth of China's economic space, as the industrial chains of Vietnam and China are closely integrated. Located right next to each other, a rich Vietnam is more beneficial to China than a poor one, so China does not need to worry too much about the challenges posed by Vietnam's rising industries.

But for India, its dividend period of labor force, its vast market hinterland, its almost-complete electronics industry chain, a more developed software and information industry, as well as its lingual connectivity with Europe and the U.S., are all preparing India to become the next world's factory, and more likely a competitor to China.

Li reckons India would be able to maintain a higher growth rate than that of China for a long time to come. And when its economy is half the size of China's, it would be able to exert substantial influence over China.

"In the short run, the substitution effect of Vietnam to China may increase, but in the long run, India will loom larger as the alternative," Xu Qiyuan said.

03 The new question: return home, or journey on?

While many firms are leaving China, Zhong Qing is mulling the idea of returning to Dongguan.

On May 10, U.S. President Joe Biden said Washington might drop some of the tariffs imposed against Chinese imports. As the news spread, Zhong, who owns a Christmas electronic craft manufacturing business in Southeast Asia, noticed that his clients' requirements for orders outside China were less stringent than before. “If possible, I'd very much like to bring most of my business back to China,” said Zhong, “Of course, it all depends on the international situation.”

Zhong came to Cambodia three years ago in 2019.

Compared with the Pearl River Delta region, Cambodia's land and labor costs are almost “dirt cheap.” Yet the country's infrastructure is so backward that to this day there is still no highways or railroads in the country.

Workers’ strikes are a challenge for almost all companies that invests in Cambodia. In Cambodia. Wages are paid twice a month, and even workers on strikes are entitled to basic wages. After receiving their paychecks, half of the employees may not bother to show up the following day. Furthermore, any overtime plans must be approved by the country's Ministry of Labour and Vocational Training, and overtime pay must be given in cash.

"It's very unlikely that the first three years (of doing businesses here) can be profitable," Zhong said. The entrepreneur from Guangdong Province who started his business from scratch is meticulous about costs and profits. Although China's labor and land costs are higher, Cambodia does not have much of an advantage when labor efficiency is taken into account.

Factory relocation is a decision made after weighing the pros and cons. For many business owners, relocation has its advantages, but it also entails building its entire production system all over again in a strange, foreign land. Initial capital input, staff training, adapting to the local environment, and dealing with numerous complex yet specific problems can also be costly.

Duan Rongbin, manager of Dongguan-based tech firm Linoya Intelligent Technology, is discreet about taking business abroad. The company's main dealing is power cords that meets safety standards of different countries across the world. Its Southeast Asian divisions are mainly responsible for the the power cords’ assembly, but raw materials for production still needs to be shipped from China - the quality of copper produced in Vietnam is lower than that from China, and the former country has no mold factories.

Duan did the math. The price of goods exported to the United States varies depending on whether they are shipped from China or Vietnam. But despite higher tariffs, shipping from China is still more profitable when costs for supply chains and labor efficiency are put into the equation.

“Simply moving our factories to Vietnam doesn't guarantee more profits,” said Duan. His company chose a different path, by providing Vietnamese enterprises with technologies and orders in exchange for shares. Thus the company was able to meet overseas clients' requirements to have supply chains outside China. Meanwhile, the company also utilized automatic production facilities to offset the higher labor cost in China.

In fact, the current round of industrial migration has been underway for a decade, and Vietnam's labor cost advantage is gradually fading. Although the monthly salary of most Vietnamese workers remains below 3,000 yuan at present, Xu Ning noticed that labor costs had increased by about 20 percent from three years ago when he set up the factory in Vietnam. Some factories will pay employees more for working overtime.

According to a business owner who has a factory in Vietnam, the average monthly salary in Vietnam is about one third of that in Dongguan. Those who take up key positions earn nearly 3,000 yuan a month, and those in non-key positions get about 2,500-2,800 yuan.

Xie believes Vietnam still has five to ten years at most in the country’s investment window, thanks to gradually rising labor and land costs. He plans to travel with fellow business owners to other parts of Southeast Asia when the COVID-19 pandemic is over, to look for new investment destinations.

Non-operational factors are also troubling Chinese enterprises abroad. For five years Wang Gang has worked tirelessly for his company in India and Vietnam, only to decide to withdraw from both countries in the end.

Wang's company specializes in electronic imaging devices such as surveillance cameras and camcorders. “I've been in the business for many years and I am confident about my products,” said Wang. “It's dealing with local officials that gives me the headache.”

Whether it is in Vietnam or India, outsiders all need to comply with a set of "rules". Whenever businesses started to picks up, one can expect countless visits from taxation, industry and commerce departments and other law enforcement departments. A small tip would suffice in the beginning, but in the end, it always spirals down to the hassle of authorities sealing the warehouses and businesses paying the unsealing fees.

“It's institutional corruption,” said Song Xin, global policy advisor with management firm Zhouzhanggui and a former China policy advisor of the European Union. She noted foreign enterprises doing business in India often find that the hierarchy of local officials in India’s political system is not absolute, and that the boundaries of jurisdiction in terms of labor division among officials in charge of different affairs are relatively vague. Those that do not know their way around could easily get lost.

Frictions in China-India relations has aggravated this uncertainty. In the past two years, India has introduced a series of restrictions on Chinese enterprises, such as banning more than 200 Chinese mobile apps, requiring prior approval for investments from neighboring countries (including China), and sweeping investigations into tax and compliance issues for almost all Chinese enterprises in India.

According to a tax firm that assists Chinese enterprises to invest in India, the number of Chinese enterprises' investing in India cliff-dived after India introduced its policy for prior approval of foreign investments. Statistically, there were hardly any more new Chinese firms.

To makes things gloomier, the tax and compliance investigations launched by Indian authorities are destroying the very foundation of Chinese enterprises' existence in India - a large number of certified accountants and company secretaries from Indian firms have refused to sign off on audits and other crucial affairs for Chinese companies' operations, just to avoid risks. All this have plunged Chinese companies into a systemic risk of non-compliance in India.

“Large companies have already invested billions in operations in India, and can't afford to give up this country,” said the head of the tax firm, “They are trapped.” But the impact of the changes is apparent: an increasing number of Chinese enterprises are becoming hesitant to invest in India, while many small and medium-sized enterprises are leaving India altogether.

“Returning to China is our way out,” said the aforementioned hardware business owner, who speaks the mind of his many peers. No Chinese company would completely close their factories in China during the relocation process. Most of them maintained or scaled down operations in their China-based factories. “At least we can go back home on a rainy day,” said the owner.

However, the relocation of industry from China to Southeast Asia is still a road that more enterprises have to take. It's only a matter of time before they "go out," and trade friction only accelerated the pace of their overseas investment. They see this relocation as an opportunity.

While building factories overseas, they are also exporting Chinese management methods. "Management must suit local conditions," Xu Ning said. One of the biggest problems faced by enterprises in Southeast Asia is strikes. Xu Ning's company work with local labor unions in Vietnam to improve employees’ care. For example, whenever the company needed to rush productions or have the workers work overtime, they would publicize the situation through unions and ask whether they would support it.

Based on his experience, Xu Ning concluded that a set of clear and detailed factory operation guidelines is a must-have. After workers finish their training, they shall go through written assessments. In addition, Vietnamese employees should learn Chinese, so they can be directly managed by Chinese management team. "Usually, they can understand a good part of the language within six months."

Wu Geming is already considering expanding the ASEAN market and using local supply chains to find new opportunities. He has set his sights beyond Southeast Asia - his next destinations for business expansion are in Mexico and Africa.

04 The restructuring: overseas expansion and domestic enhancement

This is already the fourth round of global restructuring and flow of enterprises, capital, factories, technology and many other factors of production in history. In the first round, they flowed from the U.S. to Japan, then to “the Four Asian Dragons”, and to China in the third round. Now, they are heading for Southeast Asia, India and other places.

Zhu Hengyuan, a professor with Tsinghua University's School of Economics and Management, calls the driving force behind the current restructuring a “范式变迁” “paradigm transition.”

There's a physical phenomenon called 电子跃迁 “electron transition” - electrons orbiting a nucleus are in a different energy level or orbits, and when an electron in a lower orbit absorbs enough energy, it can jump to a higher-energy orbit closer to the nucleus. Similarly, in economic development, whenever the industrial revolution occurs, transition from between different “orbits” of paradigms will ensue.

The outbound relocation of the electronics industrial chain is indeed an inevitable result of this paradigm transition. Such a transition would lead to a new industrial revolution, deconstructing the old industrial landscape as a new one emerges.

In order to understand China's position, its opportunities and its risks in this new round of industrial revolution, one need to make a distinction between two types of subjects in the outsourcing of electronic industry chain: foreign companies that invested in China, and Chinese companies. Their cases need to be discussed separately.

“For foreign enterprises, strategic competition between China and the U.S. is most prominent factor that motivates their industrial relocation,” said Li Wei. He noted that Biden’s supply chain resilience strategy, under which the U.S. accelerated the outbound relocation of supply chains from China and reduced its supply chain dependence on China, is the most important economic and diplomatic strategy his administration had pursued so far.

Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen recently called for a reshaping of trade relationships oriented around “trusted partners.” The U.S. government is now establishing a supply chain partnership with Europe, and bringing Japan and South Korea along at the same time. On one hand, it aims to bring hi-end manufacturing industry back to the U.S. On the other hand, it is trying to relocate lower-end manufacturing from China to Vietnam and India.

"The impact of the U.S. supply chain resilience strategy on China's industrial development may be much greater than that of the previous tariff war, and it will be long-term and irreversible," Li Wei said.

However, China still has the advantages of complete industrial clusters, technology accumulation and supporting facilities, and no country can replace it in the short term. According to the data of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the value-added of China's electronic information manufacturing industry above designated size saw an year-on-year increase of 15.7 percent in 2021, a new high in the past decade.

Take Apple as an example. The Chinese mainland continues to lead the world in terms of the number of factories established. Of all factories of Apple’s top 200 suppliers in the world in 2020, more than 40 percent were based on the Chinese mainland, which is about 27 percentage points higher than Japan which ranks second on the list. "Both India and Vietnam are incomparable with the Chinese mainland in terms of supply chain completeness. Conditions there are far from mature," Ivan Lam said.

However, it is worth noting that the industrial clusters in any relocation destination will grow faster and faster like a snowball, and gradually form an increasingly sophisticated industrial ecosystem. Li Wei projected that if the Yangtze River Delta does not resume normal production as soon as possible, the reactions from the supply chain will accelerate, and the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will manifest themselves this year.

For Chinese enterprises that take the initiative to "go global," industrial chain spillover itself is not necessarily a bad thing. According to Zhu Hengyuan, China’s continuous export of technology and management methods to Southeast Asia does not mean that China is losing ground in the global industrial chain. Rather, it highlights China’s resilience and strength.

He believed that the accumulation of a country's industrial capacity can never be achieved overnight. Rather, it takes time, and maybe a little luck. The accumulation of industrial capacity in China's manufacturing industry in the past 30 years is a rare occurrence in the world, and it will take a long process for other countries to do the same.

"At this stage, as long as China still boasts substantial industrial capability that is enough to be a pole in the global supply chain, the industrial chain itself cannot exit the country entirely, nor will there be large-scale decoupling," said Zhu.

For Chinese business owners, despite the large-scale migration of electronics companies into India, it seemed that funds, products, technologies, and experiences were still circulating among Chinese companies there. India has not been able to cultivate its potent, homegrown enterprises. “It's Chinese factories all along the industrial chain. As long as Chinese enterprises stay close to each other, we will still hold the advantages and initiative in our hand.”

Taking both internal and external factors into account, it is clear that although China is facing a complex political and business environment, one fact remain unchanged: the industrial chain has not completely left China, but is distributed in a decentralized fashion in many places around the world. Foreign companies are changing their strategies from of "All in China" to "China + N", but China's dominant position will not be challenged in the short term.

However, if China wants to further solidify its advantages and achieve industrial upgrade in the new wave of industrial restructuring, it needs to focus on two things at home and abroad.

The first is to build a "circle of friends" outside its borders. Li Wei believes that Europe and Southeast Asia are two strategic regions China must focus on. European countries have no strategic threat to China, and they do not see eye to eye with the United State on everything. Southeast Asia is already China's largest trading partner, and even if trade between China and western countries encounters obstacles in the future, Southeast Asia can always play the role as a transit point. Furthermore, China must cultivate friendly relations with Japan and South Korea to the best it can. Even though both countries are currently trying to reduce their economic dependence on China, China's vast market is something they can hardly part with.

Secondly, China ought to shift from "high growth" to "high quality growth" on the track of its domestic industrial development. China's biggest advantage comes from having the world's largest consumer market. From Zhu Hengyuan’s perspective, this is a most valuable environment for new technologies to emerge and develop - while all industrial revolutions originated from technology, the application of technology cannot be separated from specific market demand and everyday scenarios.

The latest round of industrial chain restructuring is the result of both the law of economics and the current global political environment. Although there is little experience for China to draw from the previous three round of industrial relocations, the general direction for the way forward is clear. According to Zhu, China needs to find new ways of industrial development in the latest round of industrial revolution. The country should not only enhance the resilience of its industrial chain structure, but also share the fruits of its own development with neighboring countries, and become the driver of common development. These will be the paramount undertaking for China for a long time to come.

***

To help make GRR sustainable, please consider buy me a coffee or pay me via Paypal. Thank you for your support!