What if you bet on right a Chinese startup? Inspiration from a South African company

Braving the new, a South African publishing company made its most successful bet on a Chinese Internet giant.

Right now, companies worldwide are desperately trying to wrap their heads around the market share of artificial intelligence chatbot, as ChatGPT - a viral chatbot developed by OpenAI - reached 100 million users in Jan. 2023, just two months after its launch in Nov. 2022.

Almost on the same day of Feb. 2023, Google and Baidu, the largest search engines in the English and Chinese worlds, both officially announced their own "ChatGPT-like" chatbots, named "Bard" and "ERNIE Bot", respectively. They all seem to know the importance of conforming to the trend of times and making a brave investment and wise reform in newly emerged things.

Over 20 years ago, Naspers, a small publishing company in South Africa, also made a proactive transformation and a smart investment in a Chinese startup on innovative instant messaging, which later became the world-leading internet and technology company -- Tencent. It turned out to be its most successful bet seen today.

Today's piece introduces the story behind the successful bet of Naspers on a Chinese internet giant Tencent at its early stage. At the dawn of the millennium, when the dotcom bubble burst, it took great courage and keen insights for an investor at the end of its tether to bet on a cash-strapped Chinese internet company nobody wanted. The secret to Naspers' success may have always been its bravery to bet on the new and take progressive transformation since its founding as a traditional print media company, then to a set-top box giant, and finally an internet hunter like a lucky slot machine.

The piece was posted on Jan. 13 on the WeChat blog named 远川研究所 "YuanChuan Institute", a company-run blog that claimed to be an independent financial think tank serving the public and committed to "bridging the gap between professional research and public cognition", integrating global in-depth research supplies, and providing customers with high-quality analysis and information. The original title of the article is Betting against the times: Who made 1 trillion HK dollars on Tencent?.

Even pigs can fly when placed against the wind, but as the original author says, no one can guarantee that the industry they are in will always be on top of the trend. When a new technology or a new model is destined to shatter the traditional format, instead of involuntarily transforming itself, it is better to bet on the top companies in the sunrise industry.

[Note: Data not clearly indicated in the article is provided by the original author for reference only.]

Today, when people look back on the adequate atmosphere and flourishing conditions once in China’s internet industry, the first thing that comes to their mind is still the love-hate relationship between Chinese entrepreneurs and top U.S. dollar venture capitalists (VCs).

The VCs from Silicon Valley, led by their Chinese partners, searched Zhongguancun Street for China’s Google, Yahoo, and Amazon. Amid the unprecedented investment frenzy, SoftBank Group founder and Chief Executive Masayoshi Son, invested 20 million U.S. dollars in Alibaba, which generated a 2,000x return. Today this success story remains reminiscent of the apex of the Korean-Japanese VC investor in the Silicon Valley, while igniting people’s imagination of investment returns.

Flights between China and the US across the Pacific Ocean and investment and financing figures on U.S. dollar funds recorded the glory days of the internet in the past.

However, until 2022, when Tencent announced that its major shareholders had made selldown in their holdings, nobody knew that the biggest winner in the fortune-making campaign was actually on the African continent far from the spotlight.

Naspers, a South Africa-based media group, has never made any influential reports about China, yet somehow became the institutional investor that understood China better than Masayoshi Son.

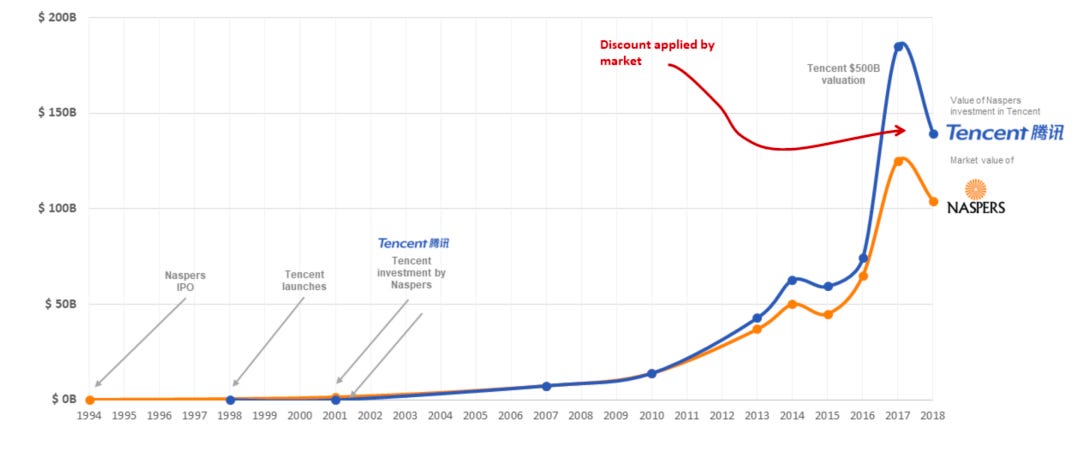

In 2001, Naspers bought a 46.5 percent stake in Tencent for 32 million U.S. dollars. The investment yielded a return of more than 7, 000x in the past two decades, during which Tencent shares surged after the firm went public in 2004. Tencent dividends to Naspers alone reached 25.2 billion Hong Kong dollars for a period of 15 years. When Tencent was in its prime, the shares held by Naspers reached as high as 2 trillion Hong Kong dollars in valuation; even when Tencent’s market value plunged later, the shares held by Naspers were still worth 1 trillion Hong Kong dollars. At any time, this investment can be considered the most successful investment story in human history.

“Tencent is the gemstone on Naspers’ crown, and also the sharpest arrowhead in the arrow bag. If Tencent coughed, Naspers would develop pneumonia,” said Ton Vosloo, former chairman of Naspers.

The success is too shining that even the reason which Naspers claimed was behind selldown in its Tencent stake sounded like humblebragging. According to Bloomberg, Naspers had long felt upset about the gap between its valuations and that of its Tencent stake, and the move was an attempt to narrow that gap.

In fact, with support from Tencent, Naspers, which started as a newspaper seller, has created a share price curve totally different from other traditional media groups after becoming public.

Comparison of cumulative returns of four media groups (Naspers, New York Times, News Corporation, Gannett Company) after listing

The question is, how did a publishing company in South Africa make its most successful bet on Tencent?

01 A South African investor that reaped nothing; a Shenzhen company nobody wanted

In the early autumn of 1995, the first commercial web browser Netscape staged an initial public offering (IPO) in the US, its shares skyrocketing at a pace that shocked the Wall Street fuddy-duddies. In August 1995, the Wall Street Journal reported, “It took General Dynamics Corp. 43 years to become a corporation worth today's 2.7 billion U.S. dollars in the stock market. It took Netscape Communications Corp. about 1 minute.”

Netscape set the IPO template for modern tech companies. With investor enthusiasm running high during the bull market at the end of the 20th century, the earliest fortune-making in the internet industry began. Investors bought into the time machine theory (The theory believes that every other country will go through the same technology transition as the US in different stages) of Masayoshi Son. Countless overseas VCs turned to China, hoping to find an IPO opportunity.

At the time, the most popular internet projects in China, including NetEase, Sina, and Sohu, were all simply named, compared with the trendy names of new entrants after them, from BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent), TMD (Toutiao, Meituan, Didi), to PKQ (Pinduoduo, Kuaishou, Qutoutiao), taken from the 26 Latin letters.

In 1998, NetEase became the highest-ranking website in Chinese internet. “Wall Street investors scrambled to invest in NetEase, which only had ten employees,” NetEase founder and CEO William Ding recalled. When Sina sought a listing, it selected Morgan Stanley as its partner. The big bosses of investment banks didn’t understand the internet, let alone Chinese internet. They caught up on early internet slang like “click-through rate” and “IPC” only ten minutes before having a meeting. But that didn't matter at all. The important thing was they could make a fortune in the ".com" business.

A digital screen outside the building of Nasdaq that read “Nasdaq Welcomes SINA.com” when Sina went public on the Nasdaq Stock Market in 2014.

Naspers far away in South Africa sniffed out an opportunity and set up an office in Hong Kong. Naspers employed the “spaghetti strategy”, where it threw a lot of pasta at the wall and believed that some would stick, given the size of the Chinese market.

Compared with Walden, Barings, and RSCO, which successfully bet on the three major Chinese web portals (Sina, Sohu, and NetEase), Naspers was walking on pins and needles after it came to China. The then inconspicuous South African company not only failed to secure a seat at the negotiating table for good projects, its “spaghetti strategy” didn’t work either.

In the late 1990s, Naspers invested in a lot of projects in China, including VNET Group, Sportscn, maibo.com, and iyfw.com. At the same time, Naspers served as a strategic investor, splashing out to help attract western senior executives to those enterprises. But in the end, the investments fizzled out as a result of the company being unaccustomed to the market climate in China and failing to find the suitable profit pattern. Naspers lost more than 80 million U.S. dollars in China.

The point was, Naspers didn’t make any money, but kept losing it.

As the Nasdaq Composite Index declined from its all-time high of 5,048 in March 2000, the dotcom bubble burst. Soon, Masayoshi Son lost 95 percent of his assets, and Naspers saw its share price shrank by 90 percent. Naspers ushered in a brand new century with negative results in its annual financial statement for the first time. With the bursting of the dotcom bubble, Naspers was beset with troubles both internally and externally.

While Naspers was considering how to get rid of those Chinese projects which had become a heavy burden in the Hong Kong office, in the Saige Technology Park across from the Shenzhen River, a small company was desperate for investments to find a way out of its plight. That was Tencent.

The first office of Tencent in the Saige Technology Park

In December 2000, Tencent released its latest version of OICQ and the software name was formally changed to QQ (nickname for OICQ). The number of users increased by 500,000 on a daily basis. The business seemed set for a flourishing future. But the question was QQ never turned a profit. The increasing servers counted on a continuous influx of money, so much so that even IDG Capital, an early backer of Tencent, considered quitting.

IDG Capital invested in dozens of internet firms. Almost all of them suffered heavily from the bursting of the dotcom bubble and were in urgent need of surviving by selling their shares. Instant messaging became a margin business surrounded by uncertainty. So IDG Capital began searching for other investors to take over Tencent.

But to be honest, there were few VCs to choose from. When all the professional VC investment managers of China in the late 90s dined together at the LN Garden Hotel Guangzhou, Mr. Xiong Xiaoge, founding Partner of IDG Capital, found they couldn’t fit the seats of even one table. IDG Capital approached big companies such as Sina, Yahoo, and Lenovo for the takeover, but all in vain.

As IDG Capital was sincerely searching for a successor, Wang Dawei (real name: David Wallerstein), vice president of China business at Naspers was wandering across China. He visited many internet cafes. Wherever he went, he could see a QQ icon on the computer screen, and some managers even printed their QQ number on their business card. Curious about Tencent, he entered its office.

Then a frustrated South African company and a cash-strapped Shenzhen firm accidentally met each other, by fate.

As Pony Ma, founder, chairman and chief executive officer of Tencent, briefed on his company, Wang was shocked that the users of QQ in China had far surpassed that of internet users across entire Africa. He excitedly explained his plan to invest in Tencent at a Naspers meeting, but it met opposition from almost all the senior executives. They didn’t agree to spend more on China, citing previous failures.

But Wang’s instinct told him he should persist in getting the deal done. Finally Naspers’ South Africa CEO Koos Bekker made a decision to invest in Tencent against all the odds. With 32 million U.S. dollars, the only cash left, Naspers purchased a 46.5 percent stake in Tencent from IDG Capital, PCCW and Tencent’s major founders, becoming its largest single shareholder.

02 Newspaper and set-top box giant, internet hunter

Yes, the company that played the role of VC in the early stage of China’s internet development actually specialized in the media business in the first place, and in the most traditional sort of media - newspaper. But continued efforts in VC, rather than its “proper business”, have turned Naspers into a growth stock.

In 2014, the market value of Naspers’ shares reached 44 billion U.S. dollars, 200 times higher from two decades ago (In 1994, Naspers went public at a valuation of roughly 200 million U.S. dollars). In comparison, its industry peer The New York Times had a market capitalization of approximately 2 billion U.S. dollars, with stock prices unchanged from the mid-1980s levels.

[GRR's note: In consideration of the article length and theme, a part of this section from the original article is omitted here. It looks back on the founding story of Naspers and its smart and timely transformation from traditional newspaper media to set-top box giant and now an internet hunter]

03 Lucky slot machine

The Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) is the largest stock exchange in Africa. Since its investment in Tencent, Naspers has had a most special presence in the exchange.

With so many investment managers relying on the exchange traded funds (ETFs) and other passive index-related instruments, both these shares now underpin the savings industry of South Africa, according to David Shapiro, chief global equity strategist at Johannesburg-based Sasfin Securities. Naspers used to have around 20 percent weighting on the JSE benchmark index, equivalent to the weight of Kweichow Moutai (a partial publicly traded, partial state-owned enterprise in China, specializing in the production and sales of the spirit Maotai baijiu) plus five Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL, a Chinese battery manufacturer and technology company) on the CSI 300 Index (a capitalization-weighted stock market index designed to replicate the performance of the top 300 stocks traded on the Shanghai Stock Exchange and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange).

Riding on the booming internet wave in China, Naspers became the core asset navigating the economic cycles in the South African market.

In early 2021 when South Africa was struggling with nationwide restrictions and large-scale unemployment amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the share prices of Tencent far away in China were moving to a record high of 775 yuan. Accordingly, the share prices of Naspers stayed firm, even sending the entire JSE upward against the headwinds of a flagging domestic economy, with all the stock indices rising 11 percent year on year.

“Naspers is essentially a holding company for a big investment in Tencent,” JSE investment managers agreed.

In addition to its stake in Tencent, Naspers has also put money into global assets that span internet finance, food delivery, and technology, among others. Some of them have proved successful. For example, educational technology startup BYJU'S, backed by Naspers along with Tencent and other corporate investors, has developed into the largest online education platform in India; Delivery Hero, an online food-delivery service based in Berlin, claims to top the Asia-Pacific region in terms of GMV (gross merchandise volume); Russian technology company mail.ru invested in by Naspers before the Russia-Ukraine war broke out is Russia’s second largest web browser.

Overview of Naspers’ investment presence in 2022 (Source: Prosus Annual Report)

Judging by the rate of return, Naspers has also reaped handsome profits from some companies. From selling some of its e-commerce activities (Flipkart and Allegro) in 2018, Naspers got a good return (Flipkart at 3.6x on and Allegro about 1.6x).

But many of the internet businesses in which Naspers has interests are still under the curse that growth comes only after an influx of money. Their profit pattern fluctuates and share prices fall and rise on a roller coaster ride. Take Delivery Hero where Naspers takes a 27 percent stake for example. Delivery Hero faces competition from emerging delivery companies across Asia. The company saw its share prices plunge 40 percent following a disappointing earnings report for 2021.

The only top student that can provide stable returns has always been Tencent.

In 2017, Tencent’s revenue grew at a rapid rate of 50 percent. At the same time, the value of dozens of other investments and businesses (including media, e-commerce, and pay TV) backed by Naspers had fallen to minus 340 billion rand in the past two years. One year later, Naspers abandoned its pledge of “holding Tencent stake for 10,000 years” and sold 2 percent of its holdings in Tencent.

The deal added 10 billion U.S. dollars to the cash reserves of Naspers, most of which went to online classifieds, food delivery, payments, and education technology. That is, Naspers took advantage of Tencent to support other disappointing projects.

Thanks to Tencent, Naspers can try its luck everywhere despite the possibility of failure. Transitioning from a media company to an equity investment company, Naspers has distinguished itself from many other media companies that are struggling to survive while being caught in the merger and split dilemma.

Fate often depends on some mysterious moment.