Exclusive: Unpacking the complexities of the 1992 Consensus

The 1992 Consensus is the political foundation for the development of cross-Strait relations and the anchor for peace and stability across the Strait

I am happy to announce that 中国社会科学院台湾研究所 the Taiwan Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) has granted Ginger River Review (GRR) the exclusive rights to launch online their full-text English quarterly journal on Taiwan-related studies -- "China Taiwan Studies".

The Taiwan Research Institute of the CASS on Dec. 25 launched the "China Taiwan Studies", the Chinese mainland's first English academic journal on pertinent issues for international readers. Wang Changlin, vice-president of the CASS, said the launch was timely against the backdrop of cross-Strait relations facing a choice between peace and war, and between prosperity and decline.

In October last year, I posted a GRR interview of 刘匡宇 Liu Kuangyu (an associate research fellow with the Taiwan Research Institute) about the circular on the cross-Strait Fujian and Taiwan integration development plan and cross-Strait relations.

In today's piece, I have selected a paper focusing on a key issue concerning cross-Strait relations -- the "1992 Consensus" or "九二共识" -- from the inaugural issue of "China Taiwan Studies". The paper, titled "30 Years of the 1992 Consensus in Retrospect," was written by Ding Yanling from the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council, and Sun Yafu from the National Society of Taiwan Studies. Sun Yafu was Deputy Secretary-General of the ARATS in 1992 and was involved in the process of reaching the 1992 Consensus.

Recognizing the extensive nature of academic research, my approach will be to succinctly highlight key sections and findings of the paper. For those who wish to delve deeper, I have uploaded the full paper in English via Google Drive for downloading and sharing with others.

In the context of the 1992 Consensus, on the one hand, officials from the Chinese mainland such as Song Tao, head of both the Taiwan Work Office of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council, have emphasized on multiple occasions that

“九二共识”是两岸关系发展的政治基础和台海和平稳定的定海神针

The 1992 Consensus is the political foundation for the development of cross-Strait relations and the anchor for peace and stability across the Strait

On the other hand, it has been observed internationally that there are differences in the understanding of the 1992 Consensus between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait. There has been even heated argument concerning the very existence and definition of the 1992 Consensus and whether it should be maintained or abolished.

Due to various reasons, the historical process of reaching this consensus requires extensive explanation, so in Part I of today's newsletter, I excerpted three paragraphs that I believe are most representative from the paper. They mainly include the content of the 1992 Consensus and why the Chinese mainland perceives the Taiwanese understanding of the 1992 Consensus, or “一个中国、各自表述” “one China, dual expressions”, to be different from its own.

Following these sections, in Part Ⅱ, I extracted the main parts describing the historical process of reaching the 1992 Consensus for readers who wish to study it in detail.

Before delving into the details of the 1992 Consensus, it's essential to introduce two special entities, which were directly involved in the formulation of the 1992 Consensus. In the context of cross-Straits relations, 海协会 the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS) (established in the Chinese mainland) and 海基会 the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF) (established in Taiwan) serve as pivotal non-governmental organizations.

This resulted in a unique arrangement in cross-Straits relations: both sides set up their respective non-governmental organizations with the authorization to communicate on issues arising from cross-Straits exchanges and work to find solutions. It was a workaround at a time when both sides of the Straits were in need of contact and consultation with their political differences unsolved (around the year of 1991). It proved to be effective.

I believe the 1992 Consensus may seem confusing to some international readers because it was reached through an “函电往返” exchange of notes or letters between ARATS and SEF, and the potential discrepancies arising from the Chinese-English translation process add to the complexity. This is why I think the publication of this English journal by the Taiwan Research Institute of the CASS is valuable.

30 Years of the 1992 Consensus in Retrospect

By Ding Yanling, Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council, & Sun Yafu, National Society of Taiwan Studies

Abstract: It has been 30 years since the 1992 Consensus was reached. This paper provides an overview of the formation process of the 1992 Consensus, expounds the important role the consensus has played, and recalls the twists and turns it has withstood in the past three decades. The paper also summarizes the historical significance of the 1992 Consensus, elaborates on its essence – both sides of the Taiwan Straits belong to one China and will work together toward national reunification, and emphasizes the importance to uphold the 1992 Consensus to develop cross-Straits relations and achieve national reunification, in an effort to provide a just account of historical facts.

Part I (Three paragraphs that I believe are most representative from the paper)

Correspondence between the mainland and Taiwan and reports by media on both sides borne witness to the fact that a consensus was reached between the ARATS and SEF in 1992. Despite differences between the two sides in the means of achieving the consensus and the way to sum it up, the very existence and the content of the consensus cannot be denied. The consensus constitutes two written statements authorized and mutually accepted by both sides, specifying the position of both sides of adhering to the one-China principle and pursuing national reunification. With regard to the political meaning of one China, the SEF and the ARATS held different views, with the former suggesting “the two sides have different cognition”, and the latter agreeing “not to touch upon it during consultations on routine affairs”. These four points construct a complete sentence: both sides adhere to the one-China principle and seek national reunification, but they differ in the cognition of the political meaning of one China, and will not touch upon it in working-level consultations. It could be simplified as “upholding ‘one China’, pursuing national reunification, seeking common ground while shelving differences and promoting consultation”. ... Su Chi, former head of Taiwan’s the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC), wrote in 2002, “The consensus was reached through correspondence and verbally stated by both sides, but correspondence is a form of exchange of notes or letters. Critics can blame a lack of a single document, but cannot deny the existence of documents or even a consensus.”

Comment: Regarding the political implication of one China, the ARATS agrees “not to touch upon it during consultations on routine affairs”. "Not to touch upon it"presumably means not to explore or discuss this matter. But if one insists on asking government officials of the PRC what "one China" is in press conferences or any other official events, what answer do you expect to get other than "the government of the PRC is the sole legal government representing the whole of China" ? I think the answer should not surprise anyone, and it's different from the context of reaching the 1992 Consensus as explained above.

As the consensus was reached by way of exchange of letters between the ARATS and SEF, both sides produced different summary on the consensus afterwards. In Minutes of Wang-Koo Talks published by the SEF in August 1993, it was stated for the first time that “our Foundation started to take into consideration the talks after both sides agreed that adherence to the one-China principle could be stated verbally by both organizations.” The KMT and Taiwan authorities also meant respective interpretations of the principle whenever the consensus was later referred to; the term “one China, dual expressions” (“一中各表”) was widely used in Taiwan ever since 1995. Concerning the mainland’s take on the consensus, the ARATS summarized it as follows in its report to the third board meeting held in January 1994: “During working-level consultations in 1992, the ARATS and the SEF of Taiwan reached a consensus that both sides shall make their respective verbal statements on the position that ‘both sides of the Taiwan Straits adhere to the one-China principle’.” This summary was facts-based and covered key elements of the consensus. First, it was unequivocal that the consensus was reached by means of “respective statements”. Second, it made it clear that the content of the statements was that “both sides of the Straits adhere to the one-China principle” rather than the political meaning of one China. This is the very essence of the consensus.

Comment: Let me try to put ARATS's position in another way: "With regard to the political meaning of one China, The SEF can say “the two sides have different cognition” and the ARATS can say “not to touch upon it during consultations on routine affairs” "-- That is what ARATS refer to when it says "both sides shall make their respective verbal statements" rather than "With regard to the political meaning of one China, The SEF says “one China is the ROC” and the ARATS says “one China is the PRC”".

Again, "Not to touch upon it" is the ARATS's preference regarding the political implication of one China during consultations on routine affairs. I think the "during consultations on routine affairs" part is also important because in the example I mentioned in the last comment, you can only expect officials of PRC to say "the government of the PRC is the sole legal government representing the whole of China" if you must ask them what "one China" is.

Certain problems arise with regard to the term of “一个中国、各自表述” “one China, dual expressions” as described by the Taiwan side. First, it doesn’t conform to the reality in the first place. In fact, “one China, dual expressions” was no more than a unilateral position and desire of the KMT. The consensus shall be summarized based on the process of cross-Straits consultation and exchange of documents and their outcome, namely respective statements of the commitment that “both sides of the Taiwan Straits adhere to the one-China principle”. This is different from the KMT’s proposition of “one China, dual expressions”. Second, the wording of “one China, dual expressions” left a semantic loophole and may lead to arbitrary interpretations under certain circumstances.

Since 1993, Lee Teng-hui displayed a growing tendency of separatism in defiance of the one-China principle. He spoke publicly against the principle and said that “the Republic of China is in Taiwan.” After Lee Teng-hui raised the “two states” theory in 1999, the MAC of Taiwan exploited the term of “one China, dual expressions” in his defense, arguing that according to the term, both sides could express their own views regarding one China.[1] This is utter distortion and violation of the essence of the 1992 Consensus.

Comment: In the paper, the authors give more examples of arbitrary interpretations of the 1992 Consensus besides the examples of Lee Teng-hui. I believe the arbitrary interpretations are also related to the changes in the political ecosystem within the island of Taiwan.

Please understand the comments I added are neither official nor authoritative, as this is a PERSONAL newsletter which does not represent the views of any organization, let alone “China.” If you have any feedback to this newsletter, feel free to write me an email: jjiang.sisu@hotmail.com

Part Ⅱ (The main parts describing the historical process of reaching the 1992 Consensus)

From March 23 to 26, 1992, the ARATS conducted its first working-level talks with the SEF in Beijing on two issues: the “tracing of and compensation for cross-Straits registered mail” and the “usage of cross-Straits notarial certificate”. Li Yafei, then head of the research department of the ARATS, and Zhou Ning, then deputy head of the consulting department, chaired the two sessions respectively. During the meeting, representatives of the SEF refused to enter into any discussion on adhering to the one-China principle, stating that they were not authorized by the Taiwan authorities to discuss political issues. However, their position during the meeting revealed Taiwan’s attempt for the status of “equivalent political entity” by emphasizing “sovereignty” and “jurisdiction”, which was an outright violation of the one-China principle. For example, the SEF suggested to adopt the authentication procedures used by diplomatic missions in foreign countries on the issue of usage of cross-Straits notarial certificate and handle registered mails in the manner of postal services between countries. Clearly, a consensus on upholding the one-China principle by both sides shall be reached as the political foundation of cross-Straits consultation, and any talks in the absence of recognition of one China would be nonstarters.

To advance bilateral talks and in response to misinterpretation of the Taiwan authorities and public concerns in Taiwan, Tang Shubei, then Executive Vice Chairman of the ARATS, elaborated on the mainland’s position on adherence to the one-China principle at a press conference on March 30, 1992, after the conclusion of the consultation. He stated, “We think that there should be no problem to use notarial certificate or trace registered mails in a country. Given the fact that the two sides have yet to be reunified at present, it is necessary to find an extraordinary solution to the issues of using these documents, tracing registered mails and compensating mail loss across the Straits.” He noted, “At a time when the two sides are not reunified, we must make it clear first that what we are discussing or working to solve are the internal affairs of a country. As is known to everyone, both the KMT and the CPC acknowledge that there is only one China, which is also explicitly stated in the reunification-related documents adopted by the Taiwan authorities. Since both sides share the one-China view, why can’t we address routine affairs in accordance with this principle?” He pointed out, “We are not going to discuss any political issue with the SEF. What we are trying to do is to confirm the fact that there is only one China. As for the meaning of one China, it’s not something we plan to discuss with the SEF.” He went on to say that “we are open to discussions on how to phrase this principle.”[1] In his statement above, Tang required the SEF to clarify its position on adhering to the one-China principle, referred to the issues as “internal affairs of a country” and clarified that his side did not request discussions on the meaning of one China, but was open to exchanges on the wording of the one-China principle. After the Beijing talks, the ARATS stated its stance in the talks as follows: The concrete issues in cross-Straits exchanges are internal affairs of China and should be resolved through consultation in accordance with the one-China principle; in business discussions, as long as the fundamental position of adhering to the one-China principle is stated, the political meaning of one China might not be discussed; the method of presentation could be fully discussed; and the ARATS is willing to listen to the opinions of the SEF and representatives of all sectors in Taiwan. The ARATS had maintained this sensible stance throughout its efforts to resolve this issue.

Due to the firm position of the mainland, the Taiwan authorities realized that it could no longer dodge a statement of adhering to the one-China principle. To achieve the policy objectives they set for bilateral consultations, the Taiwan authorities also hoped that the talks could continue and progress[2]. In April 1992, the NUC began to lead research on viable solutions, arousing widespread discussions from various sectors of Taiwan. According to the reports of Taiwan media, some research members of the MAC and NUC disapproved of the SEF accepting the one-China principle during working-level talks with the mainland. They believed that, after the adoption of Resolution 2758 by the UN in October 1971, “China” refers to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the international community. If a consensus on adhering to the one-China principle was reached during cross-Straits consultations and included in consequent agreements, it may be seen as a tacit admission that Taiwan is part of the PRC and the CPC-led government represents the only legal government of China, which would compromise Taiwan’s efforts to expand its “international space for survival” and achieve the goal of “two equivalent political entities”. People in charge of the SEF and some politicians in Taiwan, however, believed that Taiwan should not circumvent the one-China principle and that recognition of the principle would not impair Taiwan’s “pragmatic diplomacy”[3]. After three-month debate, the eighth plenary session of the NUC adopted the resolution On the Meaning of “One China” on August 1, 1992. The full text of the resolution is as follows:

“1. Both sides of the Taiwan Straits are committed to the one-China principle. However, the two sides have different opinions as to the meaning of ‘one China’. The CPC-led government regards ‘one China’ as ‘the People’s Republic of China’, and after unification, Taiwan would become a ‘Special Administrative Region’ under its jurisdiction. Our side believes that ‘one China’ refers to the Republic of China, which was founded in 1912 and has continued to exist till now; its sovereignty extends to the whole of China, but at present only covers the Taiwan-Penghu-Kinmen-Matsu area. Taiwan is indeed part of China, so is the mainland.

2. Since 1949, China has been in a temporary state of separation with two political entities governing the two sides of the Taiwan Straits. It is a fact that cannot be ignored in pursuit of unification by either side.

3. To promote development of the Chinese nation, prosperity of the country and wellbeing of its people, the government of the Republic of China formulated the Guidelines for National Unification, earnestly searched for common ground and taken actions in the direction of national unification. We hope that the mainland could adopt a pragmatic approach, get rid of prejudices, commit itself to cooperation and contribute wisdom and efforts to realize a free and democratic China where every citizen prospers.”[4]

This resolution adopted by the NUC reflected the position and attitudes of the KMT and Taiwan authorities in the early 1990s. It expressed the objective of national unification and the one-China position, despite different interpretation from that of the mainland. The mainland perceived the change in the Taiwan authorities’ attitude – from refusing the inclusion of the one-China principle in working-level talks to allowing the SEF to discuss the issue and to acknowledging unequivocally that both sides of the Taiwan Straits adhere to the one-China principle – was indeed a step forward. But it opposed defining “one China” under the framework of “the Republic of China” and “two equivalent political entities”. A leader of the ARATS released a statement on August 27, saying that “regarding the meaning of ‘one China’ in the talks between the SEF and our Association on an agreement on routine affairs, relevant party of Taiwan stated in their ‘conclusion’ on August 1 that ‘both sides of the Taiwan Straits adhere to the one-China principle’. The ARATS thinks that this affirmation is of great significance to the cross-Straits consultation on routine affairs and demonstrates that adhering to the one-China principle in working-level consultation has now become a consensus between both sides.” The statement also underscored the mainland’s consistent position that “as long as the one-China principle is observed during working-level talks, the two sides don’t have to discuss the meaning of one China.” “Our Association disagrees with the Taiwan side in its interpretation of one China. We have been consistent in the position of seeking peaceful reunification under ‘one country, two systems’ and opposing ‘two Chinas’, ‘one China, one Taiwan’ and ‘two equivalent political entities’.”[5] In its response to the resolution adopted by the Taiwan authorities, the ARATS highlighted the key point of “both sides of the Taiwan Straits adhere to the one-China principle” while expressing its disagreement to Taiwan’s interpretation of one China.

It can be seen from the above-mentioned process that although the mainland and Taiwan disagreed with each other on the political implication of one China, they shared the stance of upholding the one-China principle. This paved the way to further consultations and eventually a consensus.

Ⅱ. Reaching a Consensus: Seeking Common Ground While Shelving Differences

Following the ARATS statement on August 27, Chen Jung-chie, then Secretary General of the SEF, telephoned Zou Zhekai, then Secretary General of the ARATS, and requested a meeting. On the occasion of leading a team to hand over illegal migrants to Xiamen on September 17, Chen met with Zou and unofficially exchanged views on the way recognition of the one-China principle shall be expressed. Zou stated that “The conclusion made by the Taiwan side on the one-China principle demonstrates that both sides have reached a consensus on adhering to the one-China principle in consultation on routine affairs. However, we disagree with the Taiwan side concerning the interpretation of the meaning of one China, and we are not going to discuss the interpretation issue with the SEF.”[6] This meeting helped to strengthen mutual understanding between the two organizations.

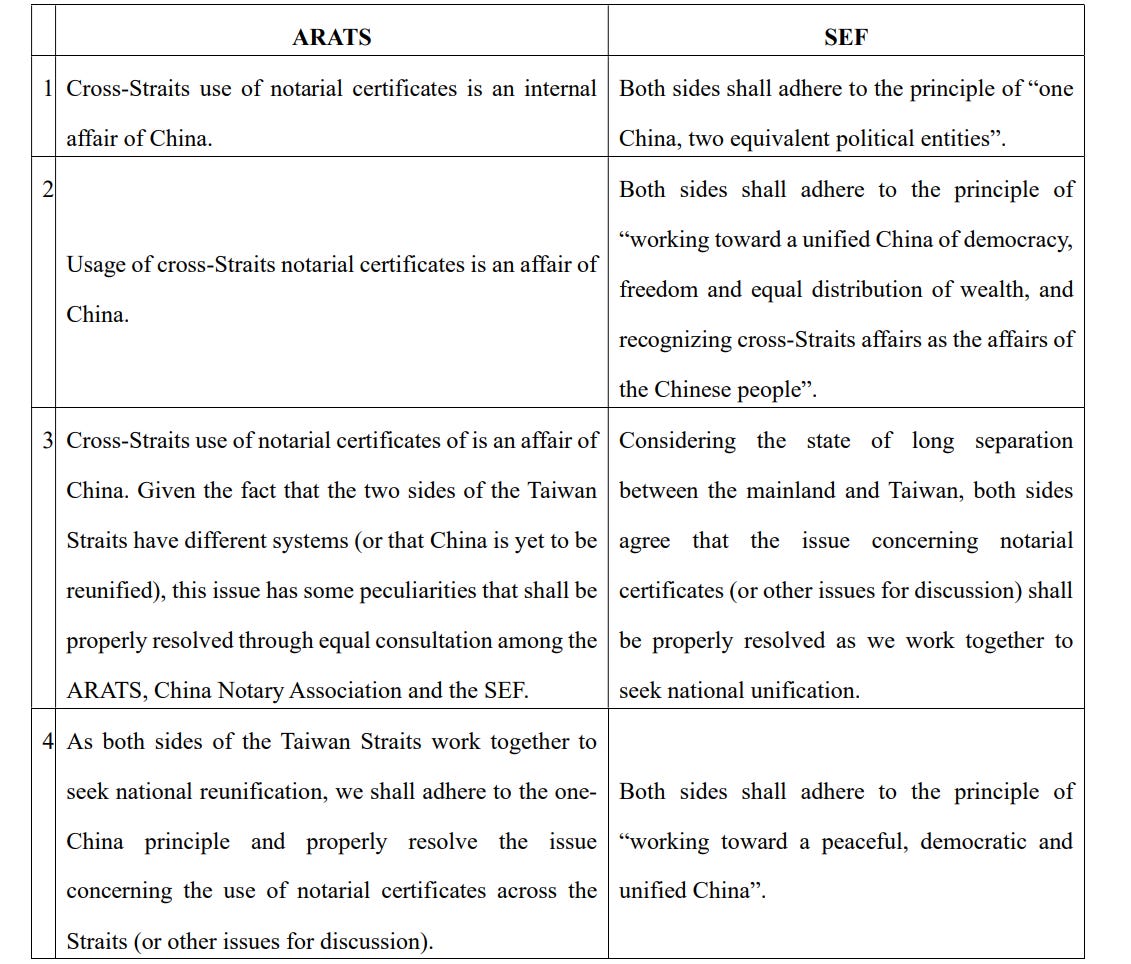

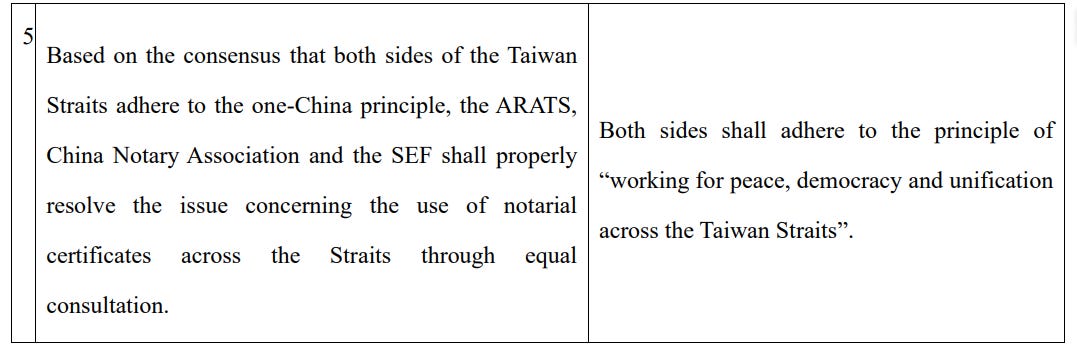

From October 28 to 30, the SEF and ARATS conducted further talks in Hong Kong on the issue of cross-Straits use and verification of notarial certificates. Zhou Ning, then deputy head of the consulting department, represented ARATS during the meeting. From the very beginning, the meeting focused on how to reach a consensus on adherence to the one-China principle in routine affairs consultations, a topic both organizations were authorized to discuss[7]. Both sides listed five written proposals respectively for deliberation (See Table 1), but none was agreed on. Upon evaluating the status quo of the meeting, representatives of the SEF concluded that since solid progress had been made in working-level consultation, the consultation outcome could suffer if the mainland’s political concern was not addressed. Therefore, during the last closed session on the afternoon of October 30, the SEF verbally presented another three proposals (See Table 2), which were well documented by ARATS representatives at the meeting. The third one was a revised version of the fourth proposal of the ARATS. The fundamental difference between the two proposals lies in the addition of one sentence by the SEF: “(While both sides adhere to the one-China principle,) they differ in interpreting the meaning of one China.” The SEF also suggested that “Both sides could orally express their positions to the extent acceptable to each other.” The ARATS representatives promised to make a formal reply to the SEF back in Beijing.

Table 1 Written Proposals of the ARATS and SEF on Adherence to the One-China Principle

Table 2 Verbal Proposals of the SEF on Adherence to the One-China Principle

Source: ARATS (2005). Historical Documentation of the 1992 Consensus. Beijing: Jiuzhou Press.

Following the Hong Kong talks, the ARATS, after an in-depth evaluation of the outcome of the meeting, concluded that the eighth proposal of the SEF was raised on the basis of the fourth proposal provided by the ARATS and confirmed the SEF’s position of seeking national reunification and adhering to the one-China principle. Although the SEF stated that both sides differ over the meaning of one China, it didn’t specify its interpretation, which conformed to the consistent position of the ARATS. Before the talks between the two organizations kicked off, it was also taken into consideration by the ARATS that “both sides could orally express their positions to the extent acceptable to each other”. Therefore, a consensus could be achieved on adhering to the one-China principle by seeking common ground while shelving differences.

It was crucial for the ARATS to ensure that the oral proposal raised by the SEF was the official position of the Taiwan authorities. On the morning of November 3, Sun Yafu, then Deputy Secretary General of the ARATS, talked with Chen Jung-chie, then Secretary General of the SEF, on the phone, saying that the Association “respects and acknowledges the proposal by the SEF” and requesting formal endorsement of the proposal from the Taiwan authorities. Sun also proposed further consultation on the content of verbal statements.[8] Xinhua News Agency and China News Service made related coverage on the issue. Late at night, the SEF issued a press release, confirming that “with approval from our supervisory body, our Foundation agrees on the form of verbal statements by both sides. With regard to the content of the verbal statements, we will deliver it in accordance with the Guidelines for National Unification and the resolution On the Meaning of ‘One China’ adopted by the NUC on August 1.”[9]

In a letter to the SEF on November 16,the ARATS reviewed the progress on the issue of adherence to the one-China principle during consultations on routine affairs and pointed out, “The SEF suggested that both organizations make their own verbal statements on the one-China principle on the basis of mutual understanding and put forth its own proposals (See appendix), which affirmed that both sides of the Taiwan Straits adhere to the one-China principle. The proposals made by the SEF were also reported by Taiwan press.” The letter also mentioned the key points of the ARATS’s verbal statement: “Both sides of the Taiwan Straits adhere to the one-China principle and seek national reunification. Cross-Straits consultation on routine affairs, however, does not involve the political meaning of one China. In line with this, the issue of the use of notarial certificates across the Straits (or other affairs alike) will be properly handled.”[10] With the letter attached the eighth proposal by the SEF. In this way, the proposal recognized by the ARATS was documented in writing, underlining the content of the consensus reached between the two sides.

On behalf of the MAC and the SEF, Lee Ching Ping, then Deputy Secretary General of the SEF, told Taiwan media on November 17, “We welcome the proposal of the ARATS in its letter on November 16 that both sides make their own verbal statements.”[11] Taiwan’s mainstream media published related reports with the following titles: “both sides of the Straits made verbal statements on the meaning of one China” (China Times Express〔《中时晚报》〕, November 17), “the ARATS agreed to verbal statements on the one-China principle” (Central Daily News 〔《中央日报》〕, November 17), “both sides of the Straits agree to make separate oral statements on the one-China principle” (China Times 〔《中国时报》〕, November 18), and “we welcome the proposal of making verbal statements on the one-China principle” (Central Daily News 〔《中央日报》〕, November 18)[12]. Though the wording was not accurate, these reports reflected the prevailing public opinion in Taiwan that a consensus had been reached between the two sides. In its reply to the ARATS on December 3, the SEF made no objection to the key points of the verbal statement raised by the ARATS in its November 16 letter. By this point, negotiation on the issue of adhering to the one-China principle during consultations on routine affairs had come to a conclusion, resulting in two verbal statements mutually accepted. The SEF and the ARATS shared the view that a consensus had been reached.

As can be seen from the above historical facts and course, the 1992 Consensus was reached as a result of equal consultation as both sides accommodated each other’s concerns and drew on each other’s opinions instead of imposing the will of one side onto the other. Although the consensus was made in the form of verbal statements by both sides, its formation process and content were well documented. Verbal statements represented the format only rather than the substance. The two statements were mutually accepted by both sides. Both sides expressed their acknowledgement of the position of “upholding the one-China principle by both sides of the Taiwan Straits” and “seeking national reunification”, which constituted the core of the consensus. Concerning the political meaning of one China, the SEF suggested “different interpretations by both sides”, and the ARATS agreed “not to touch upon it during working-level consultations” to put aside the difference between the two sides. This is how the approach of seeking common ground while shelving differences works. In this case, the common ground referred to adherence to the one-China principle and the pursuit of national reunification whereas the difference in interpretation of the political meaning of one China was put aside for the time being. To seek common ground and to shelf differences are interrelated and interdependent. At a time when political differences between the two sides of the Taiwan Straits remained unsolved, the approach of seeking common ground while shelving differences allowed the two sides to reach the consensus, which laid the political foundation for cross-Straits consultation, paved the way for the Wang-Koo Talks of 1993, and played a critical role in maintaining an institutionalized consultation mechanism between the two organizations.

Yes, congratulations on CASS. Hope you get more endorsements!

Congratulations on your CASS endorsement!

Keep up the good work!